1. INTRODUCTION

Thailand is currently prioritizing the development of its agricultural sector through an integrated approach designed to achieve balanced progress in the economic, social, and environmental dimensions at the household, community, and national levels, with a particular focus on promoting self-reliance (Ministry of Agricultural and Cooperatives, 2023). Strengthening the agricultural production base necessitates adaptation through the establishment of a robust and efficient management system. This process includes enhancing farmers’ knowledge and expertise across all facets of production and management while maintaining a balance between economic, social, environmental, and ecological considerations (Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation, 2021). These initiatives align with the broader objective of advancing national development toward sustainability, in accordance with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs provide an international framework that advocates for an improved quality of life for both farmers and consumers while fostering sustainable interactions with the environment (Ministry of Agricultural and Cooperatives, 2023; Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation, 2021).

Chiang Mai Province encompasses agricultural areas across all 25 districts. According to the Trade Policy and Strategy Office (2023), Thailand ranks among the world’s leading exporters of longan, with Chiang Mai being a key region for its production. The processing and export of longan—whether fresh, dried, frozen, or canned—are thus critical to both the province’s agricultural and processing sectors. To bolster the agricultural sector, Chiang Mai has established the Agricultural Learning Center (ALCs), which functions as a hub for transferring knowledge on production technology, management, and marketing to farmers. Additionally, the center provides agricultural services, disseminates valuable information, and integrates efforts from various agencies to address agricultural challenges and promote regional development. Presently, there are 25 primary ALCs, categorized by agricultural product, with five centers specifically dedicated to longan (Chiang Mai Agricultural Extension Office, n.d.).

Chiang Mai Province has established a network of agricultural communities, with government agencies acting as key facilitators. This initiative embodies the characteristics of a learning community, where groups of people come together to exchange and share knowledge, skills, and experiences in agriculture with a common goal. However, achieving sustainable development within these agricultural communities may be unattainable through government support alone. For any community to progress, it is essential that the members themselves take an active role in addressing local challenges and identifying their most urgent needs. Consequently, the development of a learning community necessitates fostering critical thinking among residents and encouraging their participation in all stages of development. This participatory approach equips individuals with the skills needed for critical thinking, analysis, problem-solving, and the application of knowledge, contributing not only to their personal development but also to the long-term growth of the community (Nobnop et al., 2021).

The effectiveness of a learning community can be significantly enhanced through the involvement of information professionals. These specialists are proficient in acquiring, collecting, recording, organizing, storing, maintaining, searching, disseminating, and providing information services across various formats, tailored to specific contexts (Greer et al., 2013). Their role in community engagement is pivotal, requiring not only technical expertise but also the capacity to forge positive relationships with the community. Unlike traditional information services, community engagement encompasses strategic activities that necessitate information professionals to collaborate closely with the community toward clearly defined, beneficial objectives aimed at fostering community change (Caspe & Lopez, 2018; Winberry & Bishop, 2021).

The development of longan farming communities in Chiang Mai Province highlights critical challenges faced globally by farmers in developing countries, such as accessing reliable information, fostering effective collaboration within communities, and sustaining knowledge development. These challenges are not unique to rural areas in Thailand but are also prevalent in agricultural communities across Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America. These regions often share similar characteristics, including a reliance on agriculture as a primary livelihood, limited access to government support resources, and a disparity between farmers’ information needs and the availability of expertise from information professionals (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], 2017; Tumwebaze et al., 2025).

A review of the literature reveals that while some information professionals and library and information science specialists engage with communities, their efforts predominantly focus on providing information services within the framework of academic service projects. There is a notable deficiency in research addressing community-oriented missions (Caspe & Lopez, 2018). Consequently, there is limited exploration of the roles and responsibilities of information professionals in community engagement, particularly within the agricultural sector. This research article aims to examine the development status of learning communities among longan farmers and the role of community engagement of information professionals in developing a learning community for longan farming in Chiang Mai Province. The goal is to offer guidelines for the work of information professionals, librarians, agricultural academics, and officials involved in developing agricultural learning communities. Particularly, the framework adopted here offers insights that extend beyond the local context and can contribute to understanding knowledge management and community engagement in broader settings. Specifically, the findings have implications for agricultural community development in other developing countries, where holistic approaches emphasizing collaboration and capacity-building are essential for sustainable growth (World Bank, n.d.).

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Information professionals, including librarians and information officers, hold positions across governmental and private sectors, specialized agencies, and independent entities (Greer et al., 2013). In the job market, these professionals are predominantly employed in libraries, information service centers, learning centers, archives, and museums (Mancini, 2012). Traditionally, information professionals are equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary for procuring, collecting, recording, organizing, storing, maintaining, searching, disseminating, and providing information services across various formats, in alignment with relevant objectives and contexts. However, they may lack the specialized knowledge and skills needed to address social issues, engage in action, build trust, make decisions, or solve problems—tasks that often require professionals with specific expertise in these areas. Consequently, information professionals frequently collaborate with others to perform information management duties, which may include communication efforts to enhance understanding within the community (Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium et al., 2011).

When engaged in community outreach, information professionals may apply their expertise in information science to support community engagement efforts. The conceptual framework for community engagement typically incorporates theories or practices utilized by academics and practitioners involved in community projects with the aim of effecting community change. Despite this, a review of the literature indicates that there is no specific conceptual framework tailored explicitly for community engagement work. In this context, the authors employ the Community Engagement Continuum model developed by the US National Institutes of Health. This model delineates five distinct work styles for community engagement practitioners: outreach, consulting, involvement, collaboration, and shared leadership. Each style specifies the characteristics of community relations, communication and decision-making processes, levels of participation, the positioning of entities, and anticipated outcomes (Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium et al., 2011).

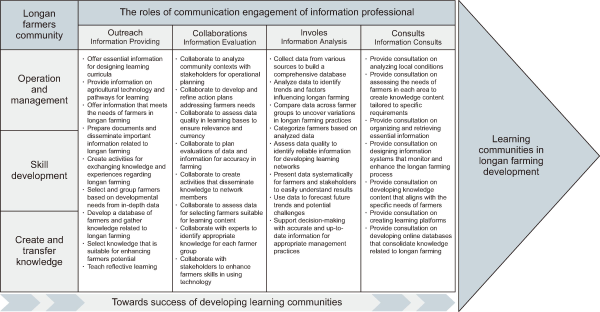

Through an analysis of the general roles of information professionals in relation to the community engagement model, as defined by the concept of community engagement, it is evident that information professionals are responsible for sourcing, collecting, recording, organizing, storing, searching, disseminating, and providing information services (Caspe & Lopez, 2018). However, they may lack the in-depth knowledge and skills necessary to address social issues comprehensively, which are essential for participating in action, building trust, and engaging in decision-making processes aimed at solving various problems. Such tasks often require the expertise of academics and professionals with specialized knowledge pertinent to the issue at hand. Consequently, information professionals must collaborate with other stakeholders to manage information-related duties and may need to engage in communication efforts to enhance understanding within the community (Winberry & Bishop, 2021). In community engagement missions, information professionals can leverage their expertise in information science across four distinct types of community engagement activities: (1) Outreach, by serving as information providers; (2) Consulting, by acting as information consultants; (3) Involvement, by functioning as information analysts; and (4) Collaboration, by serving as information evaluators (Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium et al., 2011). It is important to recognize that a single project or activity may encompass multiple roles. All these activities should have well-defined objectives, align with the community’s problems and needs, and contribute to positive change within the community.

The literature review reveals that community participation in agricultural projects or activities is generally limited to basic levels, such as providing information, offering consultations, or participating in activities organized by external agencies. This participation may take the form of ad hoc participation or involvement in formal, structured processes. However, there has been little in-depth research on higher levels of community participation, such as joint decision-making, involvement in design and implementation, or joint learning. Participation at these higher levels not only enhances farmers’ knowledge and skills but also helps build confidence and trust in the sustainable development process within the community. The role of information professionals, who can contribute beyond simply providing information or consultations by fostering higher levels of participation and facilitating more effective decision-making, represents a research gap that has not been thoroughly explored in the context of longan agriculture in Thailand.

In recent years, numerous studies have underscored the role of information professionals in school and public libraries in facilitating access to agricultural information, particularly by providing services to farmers in rural areas. Such information is critical for the advancement of agricultural professions. Research has shown that information professionals play a pivotal role in organizing and disseminating data pertaining to agricultural techniques, such as crop cultivation, pest and disease management, and market-related information, all of which farmers can utilize to make informed decisions and optimize agricultural practices. The integration of agricultural information with the needs of farmers is considered a fundamental strategy for promoting the sustainable development of agriculture, as accurate and timely data empowers farmers to adopt effective methods for improving crop yield and quality. Furthermore, it enables them to make strategic decisions regarding investments and manage potential risks arising from external factors, such as natural disasters or market fluctuations. In addition, community libraries play an essential role in enhancing access to agricultural knowledge by organizing training programs, offering consultations, and fostering learning networks within the community. This not only ensures farmers have access to valuable information but also allows them to exchange experiences and best practices for improving agricultural activities in their respective regions (Jarolímek et al., 2024; Singh et al., 2022; Yusuf et al., 2019).

Based on a review of relevant research, the role of information professionals in supporting agriculture across different regions globally is reflected through various activities. In Southeast Asia, such as in Vietnam, librarians and information professionals have developed digital platforms, such as databases, that provide farmers with access to climate information and agricultural technologies. The Smart Farmer Libraries project in Vietnam serves as a knowledge hub, enabling rural farmers to learn and apply agricultural practices (Catelo et al., 2016; Tuan, 2024). In Africa, librarians work in resource-constrained environments, providing agricultural information through community radio in countries such as Kenya and Uganda, making it easily accessible and relevant to local needs. Additionally, they promote access to information for female farmers in natural resource management to reduce gender disparities (Buehren, 2023; Ng’eno & Mutula, 2022). In Europe, librarians utilize advanced technologies such as Big Data and artificial intelligence (AI) to analyze agricultural data. For example, International System for Agricultural Science and Technology (AGRIS), a global agricultural research database, enables farmers to access essential research data quickly. Community libraries in Spain and Italy organize events that foster knowledge exchange on sustainable agriculture (FAO, 2022). In the Americas, Extension Services programs and the Ag Data Commons platform support smallholder farmers’ decision-making by providing information on crop management and marketing. Additionally, in Brazil and Mexico, libraries serve as intermediaries, connecting farmers with researchers to support the development and adoption of agricultural technologies (U.S. Department of Agriculture, n.d.).

The concept of lifelong learning has been officially recognized since approximately 1960, with United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) playing a significant role in its advocacy. Numerous global conferences have been held to discuss lifelong learning, which has led to its establishment as a fundamental principle in the educational policies of various countries around the world. Thailand first adopted the notion of lifelong learning officially in its National Education Plan of 1977 (Office of the National Education Commission, 1977). By the late twentieth century, just before entering the twenty-first century, lifelong learning had become a widely adopted approach to educational reform across many nations. This development responded to the rapid and complex changes in global society affecting economic, social, environmental, and communication aspects during the information age, which significantly impacted citizens’ lives. Consequently, countries have sought ways to ensure their citizens can engage in continuous learning to adapt to these changes (Akther, 2020).

These events led to the emergence of learning communities, which are defined as groups or communities that recognize the importance of learning and actively support the creation, sharing, and application of knowledge for the community’s benefit. These communities prioritize local needs and contexts and employ participatory processes that encourage members to think critically and utilize knowledge to solve problems. They promote continuous development of diverse skills in an environment conducive to various learning opportunities that align with individual capacities. When community members possess knowledge and skills, they can enhance their communities’ strength and sustainability (Nobnop et al., 2021).

The development of rural learning communities has gained global attention, emphasizing the role of information professionals in enhancing knowledge sharing and fostering sustainable practices. Community informatics, for example, explores how technology and information systems bridge knowledge access gaps in rural areas (Sindakis & Showkat, 2024), with professionals facilitating communication and resource-sharing. This aligns with the concept of learning communities, where collaboration and continuous learning address local challenges (UNESCO International Research and Training Centre for Rural Education, 2014). Rural knowledge management further highlights strategies for capturing and disseminating local knowledge to improve agricultural productivity and livelihoods (Akuku et al., 2021).

Studies in countries such as India and Kenya demonstrate the pivotal role of information professionals in bridging knowledge gaps within farming communities, offering insights relevant to similar efforts in Thailand. Collaborative learning, as emphasized in global research, empowers communities to share knowledge and best practices, promoting sustainable development (Siregar et al., 2024). Applying these frameworks to the Thai context underscores the significance of information professionals in supporting longan farmers, bridging knowledge gaps, and fostering sustainable agricultural practices.

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This study utilized a convergent mixed-methods approach to examine the role of information professionals in promoting the development of learning communities among longan farmers in Chiang Mai Province. Both qualitative and quantitative research methods were employed to collect data simultaneously, synthesize and analyze both phases, and present holistic findings on the role of information professionals in community engagement (Joungtrakul & Ferry, 2020).

3.1. Phase 1: Qualitative Research

Qualitative research designed to investigate the status of the development of learning communities among longan farmers in Chiang Mai Province encompasses the following aspects:

3.1.1. Population and Sample

The initial sample included ten participants: five heads of ALCs specializing in longan farming, with one representative from each center, and five longan farmers who were members of these centers. However, during data collection, four individuals declined to participate, leaving six respondents who contributed to this study. The participant selection process employed purposive sampling to ensure alignment with the study’s objectives.

The sample consisted of two main groups: (1) model farmers, who served as heads of ALCs, with one head selected from each of the five learning centers located in different districts of Chiang Mai, and (2) member farmers, who were affiliated with these learning centers. Five member farmers were initially selected based on recommendations from the center heads, ensuring that they had relevant knowledge and experience in agricultural learning and community development. Participants were required to meet specific inclusion criteria: They had to have served as an ALCs head or member for at least one year, be between 18 and 65 years old, be Thai nationals with valid identification, be in good health, have the ability to communicate fluently in Thai, and be willing and available to participate in interviews.

Interviews were conducted at the ALCs in Chiang Mai Province, a key region for longan farming in Thailand. Conducting interviews in this familiar and relevant setting facilitated authentic and context-specific responses. The discussions focused on participants’ direct experiences within ALCs, including the operational characteristics of the learning centers, methods of information exchange and sharing, access to agricultural knowledge, and the processes of information development, storage, dissemination, and curriculum design. In-depth interviews were conducted using open-ended questions, allowing participants to express their perspectives freely. Audio recordings and written notes were taken during the interviews to ensure accuracy and completeness in capturing the knowledge development processes within the agricultural community.

3.1.2. Structured Interview Design

The researchers employed structured interviews as the primary data collection tool, which were developed based on a comprehensive review of principles, concepts, theories, academic literature, and related research. The interview questions were designed to address key areas, including the operational characteristics of learning centers, management structures, and the roles of personnel, as well as methods of information exchange and practices of information sharing. Furthermore, the questions explored access to information, considering both enabling factors and constraints, and examined the processes of information development, storage, and dissemination. The design also encompassed the creation of learning curricula tailored to the needs of users. To ensure the questions aligned with the research objectives and maintained clarity and relevance, the instruments were reviewed and validated by experts in the relevant fields.

3.1.3. Data Analysis

The qualitative data in this study were analyzed using thematic analysis, following the six-phase framework proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). The analysis was conducted manually without the aid of qualitative data analysis software to allow for a more nuanced and context-sensitive interpretation. First, the interview recordings were transcribed verbatim. The researchers engaged in repeated readings of the transcripts to immerse themselves in the data and gain a comprehensive understanding of its depth and breadth. Field notes and reflective memos were incorporated to supplement the transcripts and enrich contextual interpretation.

Data coding was conducted line-by-line using an inductive approach, allowing codes to emerge naturally without relying on a predefined framework. The initial coding was performed manually to ensure that both semantic (explicit) and latent (underlying) patterns were captured. The first researcher conducted the initial coding, and a peer reviewer independently checked the codes to enhance credibility; discrepancies were discussed collaboratively. Significant features of the data were systematically coded across the entire dataset, and similar codes were organized into potential themes that aligned with the research objectives.

Potential themes were iteratively reviewed and refined for coherence and relevance. Themes were merged, separated, or discarded as necessary, and the thematic structure was checked against both the coded extracts and the complete dataset to ensure internal consistency and validity. Once the final themes were established, each theme was clearly defined and named to reflect its core meaning and contribution to the research questions. Detailed descriptions were developed to articulate the essence of each theme.

Throughout the analytic process, strategies such as incorporating field notes and reflective memos, maintaining reflexivity, and monitoring data saturation were employed to enhance the trustworthiness of the findings. Data saturation was considered achieved when no new themes or insights emerged from successive interviews. Diverse participant perspectives, including divergent or minority views, were intentionally preserved and reported to reflect the complexity of participants’ experiences.

3.2. Phase 2: Quantitative Research

Quantitative research designed to investigate the role of community engagement initiatives undertaken by information professionals in developing learning communities for longan farming in Chiang Mai Province encompasses the following aspects:

3.2.1. Population and Sample

The population in this study comprised 16 librarians or information officers working in public libraries under the Chiang Mai Provincial Learning Promotion Office, 22 school librarians under the Chiang Mai Secondary Education Service Area Office and the Office of the Basic Education Commission, and 106 agricultural academics from the Chiang Mai Agricultural Extension Office involved in promoting and developing agricultural learning communities, as detailed in Table 1. The inclusion criteria required participants to hold positions as librarians, information officers, or agricultural extension officers. Eligible participants were selected based on the following criteria: They could be of either gender, aged between 18 and 65 years, had held their positions for at least one year, demonstrated proficient communication skills in Thai, and expressed willingness to dedicate time to completing the questionnaire.

Table 1

Populations and samples

| Position | Affiliated organization | Population | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Librarians/information officers | Public libraries | 25 | 16 |

| Librarians/information officers | School libraries | 34 | 22 |

| Agricultural extension officers | Agricultural extension office | 166 | 106 |

| Total | 225 | 144 | |

The sample size was determined using Yamane (1973)’s formula, with a margin of error set at 5%. A stratified sampling method was subsequently employed to ensure proportional representation of each subgroup within the population. The population was categorized into three strata based on professional roles: (1) public library librarians or information officers, (2) school librarians, and (3) agricultural academics. Proportional sampling was conducted within each stratum to maintain consistency with their representation in the total population. This approach ensured that the sample accurately reflected the diversity of the population while upholding statistical validity and minimizing selection bias.

3.2.2. Questionnaire Design and Validation

The researcher analyzed literature and research related to the role of community engagement to gain clear insights that would guide the development of the questionnaire. The research instrument is divided into two parts: general information about the respondents, and information regarding the role of community engagement by information professionals in developing learning communities. Specifically, the questionnaire covers: 1) Outreach, 2) Consultation, 3) Involvement, and 4) Collaboration. Subsequently, the quality and validity of the instrument were assessed using an Index of Item-Objective Congruence evaluation form completed by three experts. Data were then collected from a pilot group of 30 individuals who were not part of the sample population. The instrument’s reliability was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, following Cronbach (1990)’s method, which specifies that reliability should not fall below 0.7. In this study, the instrument demonstrated a reliability score of 0.93. After confirming the instrument’s quality, revisions were made to enhance the clarity, conciseness, and overall precision of the questions.

3.2.3. Data Collection

Data were collected using an online questionnaire from individuals involved in the development of the learning community. This included 16 librarians/information officers from public libraries, all of whom returned the questionnaires, 22 librarians/information officers from school libraries, of which 20 returned the questionnaires, and 106 agricultural extension officers from the Chiang Mai Provincial Agricultural Office, with 100 returning the questionnaires. This resulted in a total of 136 respondents, representing a response rate of 94.44 percent.

3.2.4. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using statistical evaluation and descriptive analysis with IBM SPSS Statistics 30.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). The statistics employed for data analysis included the mean (χ) and standard deviation (S.D.) to interpret opinions regarding the role of community engagement from the sample group. The mean was calculated for each community engagement role (Outreach, Collaboratives, Involves, Consults) to assess the significance of each role in developing the learning community for longan farmers in Chiang Mai.

To interpret the opinions based on the Likert (1932) scale, the following criteria were applied:

-

4.51-5.00: The most significant role.

-

3.51-4.50: Very significant role.

-

2.51-3.50: Moderately significant role.

-

1.51-2.50: Lesser significant role.

-

1.00-1.50: Least significant role.

To assess the distribution of the data, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check whether the data followed a normal distribution (Shapiro & Wilk, 1965). The results of this test guided the choice of appropriate statistical analysis methods. If the data were found not to be normally distributed, non-parametric methods, such as the Friedman test, would be used instead.

Since the data collected were measurements taken multiple times from the same sample group and did not follow a normal distribution, the Friedman test was used to compare the differences between the four roles of community engagement (Friedman, 1937). The results of this test helped determine whether there were statistically significant differences between the roles.

After conducting the Friedman test to compare the roles, post-hoc analysis (pairwise comparison) was performed using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test (Wilcoxon, 1945). The significance of the differences was evaluated by adjusting the p-value using Bonferroni correction (Bonferroni, 1936) to control for Type I error due to multiple comparisons.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Qualitative Research Results on the Development Status of Learning Communities among Longan Farmers in Chiang Mai Province

4.1.1. Operation of the ALCs

The ALCs is a project overseen by the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. The process of developing farmers’ potential begins with the Department of Agricultural Extension in each province, which conducts an analysis of the learning center’s capabilities to ensure alignment with the local context. Following this, a development plan and corresponding guidelines are formulated in collaboration with the District Agricultural Office. Subsequently, an action plan is created and disseminated to all main centers and network centers.

The primary objective of the learning curriculum for farmers is to enhance their potential by equipping them with the knowledge and skills necessary for sustainable and efficient agricultural development within their communities. Designed to integrate with the Bio-Circular-Green Economy Model Agritech and Innovation Center, the curriculum enables farmers to apply appropriate knowledge and technology suited to their local contexts. It is divided into four main components: The Core Curriculum covers fundamental agricultural topics such as zoning, cost reduction, productivity enhancement, marketing management, product processing, and pest management; the Compulsory Curriculum addresses essential concepts like the sufficiency economy, new theory agriculture, integrated farming, and household accounting; the Supplementary Curriculum expands knowledge in areas such as water management, community enterprise development, business plan preparation, and supplementary careers to boost income; and the Advanced Farmer Development Curriculum focuses on enhancing business management, marketing, networking, and modern agricultural technology skills, including smart water systems and solar energy, empowering farmers to apply and disseminate this knowledge to others.

Furthermore, there is a focus on developing learning bases that serve as centers for delivering curriculum-aligned content and modern technologies. These centers are designed to showcase various innovations that farmers can apply in practice. Knowledge is gathered and cultivated at these learning bases, with integration from various agencies to bring in external resources and expertise. The ultimate goal is to maximize the benefits for farmers, including enhancing the agricultural plots of model farmers to facilitate the transfer of agricultural knowledge to interested parties. The initiative aims to teach cost-reduction methods and improve agricultural production efficiency in line with the principles of the sufficiency economy. Additionally, there is an emphasis on improving planting techniques and integrating new technologies, including the installation of educational signage on learning plots to ensure clear understanding and assist farmers in adapting to changing economic and environmental conditions.

From interviews with longan farmers in the area, it was found that most agricultural learning communities are currently at a medium to advanced level. Approximately 60-70% of farmers consistently participate in the center’s activities. Farmers who are members of the center’s network stated that “participating in activities helps us gain new and up-to-date knowledge that can be applied to our agricultural plots.” However, 30-40% of farmers do not participate regularly, citing concerns that “some training does not address the specific problems in our area, and there is no follow-up after the training.” Additionally, some farmers reported limitations in accessing resources, such as a lack of appropriate technological equipment or delays in support from relevant agencies.

These findings highlight gaps in the development of learning centers and training curricula that align more closely with local needs. Designing curricula that address specific regional challenges and establishing long-term support networks can enhance farmers’ access to relevant knowledge and resources in a sustainable manner. Furthermore, the development and expansion of digital learning platforms, such as online training modules, could help mitigate disparities in access to agricultural information and training. Additionally, sustained support from relevant agencies, along with systematic follow-up on training outcomes, remains essential for ensuring that learning centers effectively contribute to the long-term capacity building of farmers.

4.1.2. Skill Development of Longan Farmers

The ALCs have consistently organized training programs aimed at enhancing farmers’ knowledge and skills in longan farming, with an emphasis on promoting large-scale farming. The target groups include leading farmers, new farmers, members of large farming plots, and those preparing to join such plots. Following this, an analysis of the area is conducted to identify agricultural issues that require development, which are then selected as topics for two training sessions based on the planned curriculum. Additionally, a study visit focusing on relevant technologies and innovations that align with the curriculum is conducted. The training takes place at the Agricultural Extension Office, main centers, or network centers. Upon completion of the learning program, the responsible agencies record farmers’ learning outcomes to inform improvements for future training sessions.

In addition, for enhancing the skills of the heads of the ALCs specializing in longan farming, a training session was conducted, addressing key topics such as the production of safe agricultural products, the application of appropriate agricultural innovations and technologies, and the utilization of online learning platforms. Additionally, the training emphasized the connection between knowledge from the ALCs and local farmers. The Agricultural Office retains the flexibility to modify the training format or study tours to accommodate the specific conditions of each area.

ALCs therefore play a crucial role in enhancing farmers’ knowledge, with notable success stories demonstrating their impact. For instance, a Learning Center organized a training program on “Water Management for Agriculture,” enabling farmers to reduce their water usage by 30% during the dry season. Farmers in the area reported, “After the training on efficient water use, our orchards no longer experience water shortages during the dry season, and we have also been able to significantly reduce costs.”

Similarly, a Learning Center implemented a project on “Longan Value Addition,” promoting the production of high-quality dried longans. This initiative led to a 15% increase in the average household income of participating farmers. One farmer noted, “Learning about dried longan production has allowed us to sell our longans at a better price. Our income has actually increased, and now we have more money in reserve.”

These cases highlight the potential of ALCs to foster sustainable agricultural development and strengthen farming communities. By promoting agricultural innovations tailored to local contexts, such as “Water Management for Agriculture” and “Additional Career Development” programs, ALCs have effectively addressed specific challenges. In areas facing water shortages, these initiatives have significantly reduced production costs and improved efficiency. Some farmers shared their experiences, stating, “After we joined the training, we learned how to use water efficiently and could immediately apply it in our longan orchards,” and “Now we have more ways to add value to our products and can sell them at better prices than before.”

4.1.3. Creation and Transfer of Knowledge

The ALCs focus on knowledge generation through systematic analysis of agricultural situations, working with relevant agencies, committees, and network centers. This process covers identifying key agricultural problems in each area and their urgent needs, leading to the development of development plans that are consistent with the identified key problems. In the knowledge collection process, the center focuses on recording detailed data from the analysis and selection of key problems or situations in the area. It also collects data on agricultural innovations for dissemination. This data plays an important role in effective agricultural decision-making and strategy making.

For knowledge transfer, various activities focus on disseminating agricultural innovations, especially in the longan category, such as organizing exhibitions in collaboration with educational institutions, government agencies, and the private sector. These activities help promote knowledge exchange among stakeholders. At the end of the knowledge application, it was found that farmers were able to apply the innovations and knowledge they received to their cultivation and agricultural management effectively.

Last year, approximately 250 longan farmers participated in the project, with 70% of participants being able to effectively apply the innovations they learned. One example is the use of smart water systems that help reduce water usage and production costs. “The smart water system can reduce water costs by up to 30%, freeing up budgets to improve other agricultural areas,” some farmers said. Activities supported by the farmer network, such as exhibitions and community markets, also help to promote knowledge exchange and increase access to new markets. “The network helps us learn new techniques, such as using organic fertilizers that are suitable for our local soil, and also allows us to sell our products to a wider market, especially at the annual exhibition,” said one farmer.

In addition, farmers from resource-poor rural areas stated that “Although we started with difficulty accessing information, these activities have given us new directions and hopes for community development.” The results also indicated that farmer networks and community enterprise groups play an important role in expanding knowledge through activities such as training, exchanging experiences, and developing community products. Farmers who joined community enterprise groups stated that “Groups help us share problems and find solutions together, giving us more opportunities to develop products and increase income than working alone.”

4.2. Quantitative Research Results on the Role of Community Participation by Information Professionals in Developing a Learning Community for Longan Farming in Chiang Mai Province

According to the results presented in Table 2, the overall analysis of the data indicates that the roles associated with community engagement undertaken by information professionals significantly contribute to the successful development of learning communities among longan farmers in Chiang Mai Province, with a high success rate ( =3.83). Among these roles, outreach activities involving information provision and collaborative roles involving information evaluation are identified as the most impactful in fostering the development of learning communities, each rated at a high level ( =3.88). Subsequent roles include involvement through information analysis ( =3.80) and consulting through information consultation ( =3.77).

Table 2

Community engagement roles of information professionals

| Community engagement roles of information professionals | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Outreach (Information Providing) | 3.88 | 0.71 |

| 2. Collaboratives (Information Evaluations) | 3.88 | 0.78 |

| 3. Involves (Information Analysis) | 3.80 | 0.78 |

| 4. Consults (Information Consulting) | 3.77 | 0.72 |

| Total | 3.83 | 0.68 |

When evaluating the outreach aspect of information provision and service delivery, it was observed that the role of information professionals in offering services that align with the needs of users significantly contributes to the successful development of learning communities, with a high level of effectiveness ( =3.94). Following this, the provision of information services that are well-suited to community needs, the regular dissemination of up-to-date information for learning and career advancement ( =3.91), and the preparation of documents for community dissemination to facilitate mutual learning ( =3.87) are also important roles (Table 3).

Table 3

Outreach roles of information professionals

| Roles | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Providing information services that meet needs | 3.94 | 0.78 |

| (2) Providing appropriate information services | 3.91 | 0.80 |

| (3) Preparing documents and disseminating them to the community for regular joint learning | 3.87 | 0.85 |

| (4) Disseminating up-to-date information for regular learning and career development | 3.91 | 0.83 |

| (5) Creating databases, websites, and information systems to collect, store, and disseminate information to the community | 3.78 | 0.82 |

| Total | 3.88 | 0.71 |

In the context of collaborative roles as information evaluators, it was found that the involvement of information professionals in partnering with farmers and community members to evaluate data analysis results significantly contributes to the successful development of learning communities, achieving a high level of effectiveness ( =3.94). This is followed by collaboration with agricultural experts in evaluating data analysis results ( =3.93), and cooperation in assessing the quality of information based on the accuracy and reliability of agricultural data sources ( =3.87) (Table 4).

Table 4

Collaborative roles of information professionals

| Roles | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Collaborating in the planning of agricultural information quality assessments that are aligned with the specific context of the community | 3.82 | 0.84 |

| (2) Cooperating in the evaluation of information quality based on the accuracy and reliability of agricultural information sources | 3.87 | 0.85 |

| (3) Working with agricultural experts to assess the outcomes of data analysis | 3.93 | 0.83 |

| (4) Collaborating with farmers and community members in the evaluation of data analysis results | 3.94 | 0.87 |

| Total | 3.88 | 0.78 |

Furthermore, analysis of the consulting roles as performed by information consultants revealed that advising on the creation of knowledge content tailored to farmers is the most significant role for information professionals in fostering the success of learning communities, with a high mean score ( =3.84). This was followed by consulting on the use of information technology to support collaborative learning ( =3.82) and advising on the exchange and sharing of knowledge suitable for farmers ( =3.79), respectively (Table 5).

Table 5

Consulting roles of information professionals

| Roles | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Providing consultation on the planning and development of information resources, including needs assessments and the formulation of plans for the storage and retrieval of information essential for learning and development | 3.76 | 0.79 |

| (2) Offering consultation on the creation of knowledge content tailored to the needs of farmers | 3.84 | 0.92 |

| (3) Providing consultation on the exchange and sharing of knowledge that is relevant and beneficial for farmers | 3.79 | 0.88 |

| (4) Offering consultation on the use of information technology to support collaborative learning initiatives | 3.82 | 0.78 |

| (5) Providing consultation on the development and maintenance of online learning environments for communities, including websites, learning platforms, and online communities | 3.66 | 0.87 |

| Total | 3.77 | 0.72 |

In examining the role of involvement as an information analyst in Table 6, it was determined that the most impactful contribution of information professionals to the development of successful learning communities was their collaboration with agricultural experts to analyze information that aligns with the specific needs of the community ( =3.87). This was followed by their role in systematically and reliably presenting the results of information analysis, including advantages and disadvantages ( =3.81), and by their provision of guidelines for analyzing and comparing quality and reliable information for the community ( =3.78).

Table 6

Involvement roles of information professionals

| Roles | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Engaging in data analysis to understand community needs and trends, in order to formulate suitable development guidelines and plans | 3.75 | 0.83 |

| (2) Presenting the community with guidelines for data analysis and comparisons that are both reliable and of high quality | 3.78 | 0.85 |

| (3) Collaborating with agricultural experts to analyze information that aligns with the specific needs of the community | 3.87 | 0.89 |

| (4) Contributing to the systematic and reliable presentation of data analysis results, highlighting both advantages and disadvantages | 3.81 | 0.88 |

| Total | 3.80 | 0.78 |

Based on analysis of the normality test results for the data from all four roles: 1) Outreach (Information Providing), 2) Collaboratives (Information Evaluation), 3) Involves (Information Analysis), and 4) Consults (Information Consulting), the Shapiro-Wilk test (Shapiro & Wilk, 1965), which is commonly used for testing normal distribution in cases with small to moderate sample sizes, was applied. The test results showed that the p-value<0.05 for all roles, indicating that the data does not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, a non-parametric analysis using the Friedman test was conducted to compare the importance of the four roles. The results revealed significant differences in the participants’ views (χ2 (3)=Friedman value, p=0.024), indicating that the participants perceived some roles as more important than others in developing the learning community for longan farmers.

For the next step, the researcher conducted a post-hoc analysis using pairwise comparison with the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test to compare all six pairs: 1) Outreach vs. Consult, 2) Outreach vs. Involve, 3) Outreach vs. Collaborative, 4) Consult vs. Involve, 5) Consult vs. Collaborative, and 6) Collaborative vs. Involve. The p-value was then adjusted using Bonferroni Correction to control for Type I Error, using the formula p-adjusted=p-original×number of comparisons (n). The p-values after adjustment and the original p-values from the pairwise comparisons are reported in Table 7.

Table 7

Pairwise comparisons

| No | Comparison pair | Original p-values | Adjusted p-values | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Outreach (Information Providing) vs. Consults (Information Consulting) | 0.001 | 0.006 | Significant |

| 2 | Outreach (Information Providing) vs. Involves (Information Analysis) | 0.028 | 0.168 | Not significant |

| 3 | Outreach (Information Providing) vs. Collaboratives (Information Evaluations) | 0.985 | 1.00 | Not significant |

| 4 | Consults (Information Consulting) vs. Involves (Information Analysis) | 0.574 | 1.00 | Not significant |

| 5 | Consults (Information Consulting) vs. Collaboratives (Information Evaluations) | 0.035 | 0.21 | Not significant |

| 6 | Involves (Information Analysis) vs. Collaboratives (Information Evaluations) | 0.051 | 0.306 | Not significant |

The pairwise comparison analysis using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test, along with p-value adjustment using the Bonferroni Correction, revealed a statistically significant difference in Role Pair 1 (p-adjusted=0.006), whereas no significant differences were observed for Role Pairs 2 to 6 (p-adjusted>0.05). Adjusted p-values exceeding 1.0 were reported as 1.0, following standard statistical conventions to ensure clarity and accuracy in interpretation. This adjustment did not influence the conclusions derived from the analysis.

In summary, the study found that the Outreach role (Information Providing) and Collaborative role (Information Evaluation) had identical mean scores of 3.88, indicating that both roles were perceived as similarly important. However, the S.D. for the Collaborative role was higher (0.78) compared to Outreach (0.71), reflecting greater variability in perceptions of the Collaborative role. While some respondents recognized the long-term significance of collaboration, others may not currently perceive its importance, possibly due to the absence of effective collaborative efforts.

Conversely, the Outreach role received more consistent evaluations, reflecting a shared acknowledgment of its importance in rapidly disseminating actionable information. Such information can be immediately applied to address agricultural issues, such as maintaining longan trees or responding to natural disasters. These findings suggest that the Outreach role is the most critical in the context of developing learning communities for farmers in Chiang Mai, particularly when timely information is essential to address pressing issues. At the same time, the Collaborative role, which is crucial for long-term development, may not yet demonstrate its full potential due to the lack of effective collaboration between farmers and agricultural professionals in certain areas.

In conclusion, prioritizing the Outreach role represents an effective starting point for developing learning communities, such as through organizing training programs or promoting knowledge dissemination via accessible and rapid channels. Simultaneously, efforts to develop the Collaborative role are necessary to ensure long-term sustainability by fostering partnerships between farmers and agricultural professionals within the community.

Upon obtaining the research findings from both phases, namely the qualitative results on the current status of learning community development among longan farmers in Chiang Mai Province and the quantitative results regarding the role of community participation by information professionals in the development of a learning community for longan farming, the researcher subsequently integrated these findings to provide a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the development of learning communities and the contributions of information professionals in supporting the agricultural community. This integration aimed to establish a comprehensive and context-specific operational guideline for the learning community, as illustrated in Fig. 1, which presents a holistic overview of the research findings. The study emphasized the role of information professionals in supporting the relationship-building mission, focusing on four key functions: (1) outreach or information provision, (2) collaboration or information evaluation, (3) involvement or information analysis, and (4) consultation or information advising (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the findings revealed that agricultural communities in various areas of Chiang Mai Province already have organized longan farmer groups, such as the ALCs, which operate under the supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives. The researcher also examined the current operational processes of these centers, focusing on the development of farmers’ skills, both among center leaders and network members, as well as the forms of knowledge creation and transfer.

Fig. 1

Roles of community engagement of information professionals. ALC, Agricultural Learning Center.

Fig. 2

Community engagement roles of information professionals in developing longan farmer learning communities.

The integration of quantitative and qualitative findings provided a deeper understanding of the roles of information professionals in developing learning communities for longan farming. Quantitative results indicated that outreach activities and collaborative roles were highly influential ( =3.88), while information analysis and consultation also played important roles ( =3.80 and =3.77, respectively). These findings were further elaborated by qualitative insights, where participants described how information professionals actively engaged in building trust through outreach, fostering cooperative learning environments, and tailoring information services to local needs.

For instance, while the quantitative results highlighted that outreach activities were highly valued ( =3.88), qualitative data from interviews emphasized the importance of continuous engagement and trust-building efforts in sustaining long-term relationships within the community. Participants explained that the outreach role involved not only information dissemination but also maintaining a constant presence in the community to foster collaboration and ensure that the information provided met farmers’ evolving needs. This qualitative insight complements the quantitative data, stressing the sustained effort required for successful outreach and the critical role it plays in enabling farmers to take immediate action based on timely and relevant information.

Similarly, the collaborative role was rated as highly influential ( =3.88) in the quantitative results, and this was further enriched by qualitative findings. Interviewees explained that collaboration involved working closely with farmers to understand their unique needs, create customized solutions, and ensure the relevance of the information provided. This collaboration also aligned data collection with development goals, ensuring that the shared information was both accurate and actionable. The qualitative data revealed how successful collaborations were vital in addressing long-term agricultural challenges, with the support of information professionals directly improving farming practices.

The information analysis role, with a mean score of 3.80 in the quantitative results, was supported by qualitative data showing how information professionals systematically collected and analyzed data on variables such as weather patterns, soil conditions, and farming technology. This analysis enabled farmers to make informed decisions and adapt their practices based on data-driven insights. Participants spoke about how this role helped them predict and anticipate challenges, such as climate variations or pest outbreaks, that could affect crop yields.

Finally, the consultation role, with a mean score of 3.77, was supported by qualitative findings that described how information professionals guided farmers through specific agricultural challenges. Farmers emphasized the value of expert advice in making informed decisions on pest control, soil management, and overall crop health. The consultation provided by information professionals was considered essential not only for short-term problem-solving but also for long-term sustainable agricultural development.

The integration of these two strands revealed that while quantitative trends provided clear ratings of the roles, qualitative narratives enriched the understanding of how these roles were implemented and their contextual challenges. For example, although outreach activities were highly rated quantitatively, qualitative interviews illustrated the importance of continuous presence and relationship-building efforts in sustaining community trust. In this way, the two strands of data complemented and triangulated each other, offering a comprehensive and nuanced interpretation of the roles and contributions of information professionals in fostering learning communities for longan farming.

5. DISCUSSION

The research findings regarding the role of information professionals in supporting community engagement among farmers highlight the significance of having information experts in creating sustainable learning communities for farmers, especially in the context of longan farmers in Chiang Mai Province. Information professionals play a crucial role in connecting necessary agricultural information between farmers and appropriate sources. The dissemination of high-quality and relevant information can enhance the potential for collaborative learning among farmers (Idiegbeyan-Ose et al., 2019; Mia, 2020). Their role in evaluating information and transferring knowledge about data assessment to farmers enables them to make decisions and assess the value of using the information in agricultural practices independently, which promotes sustainable learning and enhances the community’s ability to self-rely (Junaidi, 2022; Rufaidah & Junaidi, 2022).

The research also underscores the importance of collaboration between information professionals and farmers in exchanging information and jointly developing data evaluation skills. Working with farmers to identify key data for decision-making, such as crop selection, planting plans, or resource management, helps farmers develop the knowledge and skills necessary to adapt and enhance agricultural practices effectively (Wolfert et al., 2017). Additionally, information professionals act as consultants in data management and promote the use of appropriate tools and technologies to exchange information among farmers, focusing on developing sustainable and efficient agricultural outcomes (Lee et al., 2020).

A review of relevant literature and studies related to agricultural support in various regions worldwide demonstrates that information professionals in Southeast Asia, such as in Vietnam, have developed digital platforms, such as databases, that help farmers easily access information about climate conditions and agricultural technologies (Catelo et al., 2016; Tuan, 2024). Projects like the Smart Farmer Libraries in Vietnam are excellent examples of using technology to promote learning and agricultural development in rural areas. In Africa, the use of radio broadcasts and community radio to disseminate agricultural information in resource-limited areas is also an essential strategy (Buehren, 2023; Ng’eno & Mutula, 2022).

In the Americas, information professionals in the United States have supported farmers through Extension Services programs and the Ag Data Commons platform, which provides information on crop management and marketing, helping to support farmers’ decision-making. They also connect farmers with researchers to promote agricultural technology development in Brazil and Mexico (U.S. Department of Agriculture, n.d.). In Europe, information professionals utilize advanced technologies such as Big Data and AI in agricultural data analysis, with the AGRIS database—a global agricultural research database—allowing farmers to access critical research information quickly. Furthermore, community libraries in Spain and Italy have organized activities that promote knowledge exchange on sustainable agriculture (FAO, 2022).

When considering and comparing the research and roles of information professionals in supporting agriculture across various regions globally, it is evident that, whether in Asia, Africa, Europe, or the Americas, the important role of information professionals in supporting the creation and development of learning communities for farmers is universally recognized. This is especially true in terms of providing necessary, high-quality information to support agricultural decision-making, which enables farmers to develop skills in assessing and using information to improve their agricultural methods. Information professionals serve as consultants in data management and facilitate knowledge exchange among farmers for collaborative learning (Junaidi, 2022; Mia, 2020). Additionally, digital platforms that enable farmers to access up-to-date agricultural information, such as climate and agricultural technology databases, are being developed (Catelo et al., 2016).

However, our research focuses specifically on the context of longan farmers in Chiang Mai, where the role of information professionals is applied to managing data specifically related to longan farming and the selection of suitable agricultural technologies. Research from other areas highlights the role of information professionals in various global regions, including the use of radio broadcasts in Africa and advanced technologies such as AI and Big Data in Europe (FAO, 2022; Ng’eno & Mutula, 2022), demonstrating the diversity of approaches used in different regions. Thus, the role of information professionals in promoting community engagement among farmers not only contributes to agricultural development but also enhances the sustainability and adaptability of farming communities in all regions. This is a key element in fostering the sustainable development of agriculture in the future.

6. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The role of information professionals is pivotal in fostering an environment conducive to learning for longan farmers. These professionals act as intermediaries, connecting the farming community with essential information resources crucial for their agricultural activities. They play a significant role in the development of learning communities by providing and maintaining access to relevant information, which enhances the farmers’ capacity for collective learning.

Information professionals also contribute by delivering knowledge and facilitating skill development, enabling farmers to acquire in-depth knowledge applicable to their farming practices. Collaboration between information professionals, farmers, and agricultural experts ensures the provision of high-quality, evaluated information that supports learning activities. In addition to their role in information evaluation, teaching farmers how to independently assess valuable information and organizing knowledge assessments empowers them to make informed decisions. This collaborative learning process fosters the development of sustainable learning communities.

Moreover, information professionals serve as information analysts, addressing farmers’ needs by helping them make informed decisions related to agricultural operations, such as crop selection, optimal planting times, and resource allocation. A learning community approach, centered on relevant and community-specific information, positively influences the creation of effective development plans. Information professionals also act as consultants, assisting farmers in identifying critical knowledge and facilitating the management and exchange of data within farming communities. Their role in recommending and developing appropriate learning media further fosters a culture of continuous learning and adaptation.

With Thailand’s robust Internet infrastructure, farmers are increasingly utilizing social media. Consequently, it is essential to enhance their capacity to leverage digital technology for practical benefits and innovation. Information professionals can play a crucial role in cultivating information literacy skills among farmers, enabling them to access reliable sources, critically assess the quality of information, and apply it ethically. Moreover, by equipping farmers with knowledge of digital technology’s potential, they will be better positioned to navigate emerging challenges and adapt to technological advancements. This, in turn, will foster the rapid development of longan farming communities as farmers share and apply knowledge collaboratively, contributing to sustainable community development.

While this study focused on the context of longan farmers in Chiang Mai, Thailand, its findings provide a foundation for broader applications in global agricultural environments. The framework for developing learning communities and the roles of information professionals identified in this research can be adapted to various agricultural and socio-economic settings. For example, in resource-constrained regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia, integrating digital tools with community engagement strategies can enhance agricultural productivity and sustainability.

Moreover, cultural adaptation is essential to ensure the success of such initiatives. In collectivist societies, for instance, leveraging traditional knowledge and local networks can foster trust and facilitate knowledge exchange. Similarly, regions with significant economic disparities may benefit from low-cost educational resources and partnerships with international organizations to bridge technological gaps.

This research underscores the importance of designing community engagement strategies that prioritize effective information dissemination and long-term sustainability. Establishing global networks of learning communities could promote the exchange of best practices and drive innovation in agricultural education. Future research should explore cross-cultural adaptations to refine and expand the utility of this framework to diverse agricultural ecosystems worldwide.

However, to maximize the impact of information professionals in supporting longan farmers and fostering sustainable learning communities, it is essential to strengthen their role through targeted training, collaborative partnerships, and digital integration. Training programs should be designed to enhance their ability to evaluate and utilize agricultural information effectively. Establishing collaborative networks between information professionals, farmers, and agricultural scholars at various levels will promote knowledge sharing and interdisciplinary cooperation. Additionally, integrating traditional agricultural wisdom with modern technological advancements will ensure that farmers can access a holistic knowledge base. Developing an easily accessible agricultural information database will further empower farmers by providing reliable, localized information in user-friendly formats. By implementing these recommendations, the role of information professionals in agricultural learning communities can be significantly enhanced, leading to improved knowledge dissemination and long-term sustainability.

7. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The qualitative research section of this article has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The sample consisted of model longan farmers who are heads of ALCs for longan farming, with only five heads of ALCs in Chiang Mai. Additionally, five members of the ALCs were included, making a total of ten participants. The purposive sampling method was used to select participants with direct experience in longan farming. While some participants were unable to provide data (4 out of 10), the data obtained from these participants still offer valuable insights. These findings are relevant and can be applied to similar agricultural contexts, particularly in regions with comparable longan farming practices or operations.

REFERENCES

(2020) Influence of UNESCO in the development of lifelong learning Open Journal of Social Sciences, 8, 103-112 https://www.scirp.org/pdf/jss_2020030911335598.pdf. Article Id (other)

, , , (2021) Knowledge management strategies adopted in agricultural research organizations in East Africa Information Development, 37, 671-688 https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666920968165.

, (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101 https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

(2023) Gender & agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa: Review of constraints and effective interventions https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/19966f50-f68b-42c9-9088-9098dfaca729/content Article Id (other)

, (2018) Preparing the next generation of librarians for family and community engagement Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 59, 157-178 https://www.jstor.org/stable/90025869. Article Id (other)

, , (2016) Economic instruments in environmental and natural resource management in Southeast Asia and China: Lessons and way forward https://ideas.repec.org/p/sag/seappr/2016326.html Article Id (other)

Chiang Mai Agricultural Extension Office (n.d.) Agricultural Productivity Improvement Learning Center (APILC) https://chiangmai.doae.go.th/province/?page_id=4484 Article Id (other)

Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium, Community Engagement Key Function Committee, Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, United States, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.) (2011) Principles of community engagement (second edition) https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11699 Article Id (other)

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2017) Information and communication technology (ICT) in agriculture: A report to the G20 Agricultural Deputies https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/fa02c775-19fc-4a1f-b0a1-9369ac776854 Article Id (other)

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2022) AGRIS: The International System for Agricultural Science and Technology https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/bb0e3f59-6e95-47db-9d3c-524197e8a869/content Article Id (other)

(1937) The use of ranks to avoid the assumption of normality implicit in the analysis of variance Journal of the American Statistical Association, 32, 675-701 https://doi.org/10.2307/2279372.

, , , (2019) Relationship between motivation and job satisfaction of staff in Private University Libraries, Nigeria Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 18, 1-13 https://www.abacademies.org/articles/relationship-between-motivation-and-job-satisfaction-of-staff-in-private-university-libraries-nigeria-7894.html. Article Id (other)

, , , , , (2024) Plant, Soil and Environment (Vol. 70) Information sources in agriculture, 11, pp. 712-718, http://dx.doi.org/10.17221/361/2024-PSE

, (2020) Mixed methods research: Applying six mixed methods research strategies Governance Journal, 9, 27-53 https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/gjournal-ksu/article/download/242505/164555/. Article Id (other)

(2022) Agricultural information literacy by urban agricultural communities in agricultural library laboratory based on social inclusion Visi Pustaka, 24, 161-170 https://doi.org/10.37014/visipustaka.v24i2.2858.

, , (2020) The choice of marketing channel and farm profitability: Empirical evidence from small farmers Agribusiness, 36, 402-421 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.21640.

(2012) The rise of the information professional: A career path for the digital economy https://computhink.in/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Rise-of-the-Information-Professional-White-Paper.pdf Article Id (other)

(2020) The role of community libraries in the alleviation of information poverty for sustainable development International Journal of Library and Information Science, 12, 31-38 https://doi.org/10.5897/IJLIS2020.0942.

Ministry of Agricultural and Cooperatives (2023) Five-year operational plan of the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (2023-2027) https://www.moac.go.th/about-strategic_plan_cost?utm_source=chatgpt.com Article Id (other)

Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation (2021) [Action plan for driving Thailand's development with the BCG economic model 2021-2027] https://www.moac.go.th/about-strategic_plan_cost?utm_source=chatgpt.com

, (2022) Handbook of research on academic libraries as partners in data science ecosystems IGI Global Scientific Publishing Research data management in Kenya's Agricultural Research Institutes, pp. 334-361, https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-9702-6.ch016

, , , , (2021) Learning community and community development Journal of Local Management and Development Pibulsongkram Rajabhat University, 1, 97-111 https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jclmd_psru/article/view/248509. Article Id (other)

Office of the National Education Commission (1977) [National education plan 1977] Thai. https://online.fliphtml5.com/uqocz/scmy/#p=1 Article Id (other)

, (2022) Evaluation of the information literacy program during library visit day activities Visi Pustaka, 23, 197-206 https://doi.org/10.37014/visipustaka.v23i3.996.

, (1965) An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples) Biometrika, 52, 591-611 https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/52.3-4.591.

, (2024) The digital revolution in India: Bridging the gap in rural technology adoption Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13, 29 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-024-00380-w.

, , (2022) Agriculture-based community engagement in rural libraries Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 54, 404-414 https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006211015788.

, , (2024) Empowerment of rural communities through information technology (IT) training for teenagers International Journal of Community Service Implementation, 1, 117-124 https://afdifaljournal.com/journal/index.php/ijcsi/article/download/195/180. Article Id (other)

Trade Policy and Strategy Office (2023) [Deputy Minister of Commerce recommends accelerating the expansion of new fruit export markets and stimulating domestic consumption] Thai. https://tpso.go.th/news/2312-0000000016 Article Id (other)

(2024) Agricultural practices and climate resilience: Case study in Vietnam International Journal of Climatic Studies, 3, 24-36 https://doi.org/10.47604/ijcs.2476.

, , (2025) Knowledge management in the agriculture sector: A systematic literature review Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 23, 131-148 https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2024.2359419.

UNESCO International Research and Training Centre for Rural Education (2014) Rural learning community for sustainable rural transformation https://inruled.bnu.edu.cn/docs/2021-09/20210916171829949633.pdf Article Id (other)

U.S. Department of Agriculture (n d.) Ag Data commons user guide https://www.nal.usda.gov/services/agdatacommons Article Id (other)

(1945) Individual comparisons by ranking methods Biometrics Bulletin, 1, 80-83 https://doi.org/10.2307/3001968.

, (2021) Documenting social justice in library and information science research: A literature review Journal of Documentation, 77, 743-754 https://doi.org/10.1108/jd-08-2020-0136.

, , , (2017) Big data in smart farming - A review Agricultural Systems, 153, 69-80 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2017.01.023.

World BankAgriculture and rural development https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/knowledge-for-change/brief/agriculture-and-rural-development Article Id (other)

, , , , (2019) Role of public libraries in promoting youth participation in agriculture in Nigeria: Information as a key driver https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2877. Article Id (other)