1. INTRODUCTION

Cultural capital is increasingly recognized as a fundamental resource for sustainable development. It encompasses intangible elements such as beliefs, thoughts, and creativity; tangible cultural products, including books, images, and world heritage; and institutional aspects such as norms and collective recognition. The accumulation of cultural capital shapes individual and collective “taste,” reinforcing social stratification and identity (Bourdieu, 1986). Culture is also a convertible form of capital that influences perceptions and lifestyles and can be transformed into economic value (Griswold, 2004). In creative industries, cultural capital contributes to value-added production, resulting in culturally enriched goods and services (Department of Cultural Promotion, 2019). Proper management of these resources is essential for preserving cultural heritage, fostering social cohesion, and promoting local economic development (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2011). One effective tool for this purpose is the community information system (CIS), which supports the collection, organization, and analysis of data to inform decisions and drive development initiatives.

Despite the recognized value of cultural capital, communities in Thailand continue to face challenges in managing these resources effectively. The absence of structured, comprehensive data systems has led to fragmented and underutilized information. Current data management practices often focus on isolated types of cultural capital, particularly tangible assets, while neglecting the broader cultural context and intangible elements. Moreover, the datasets frequently lack integration, consistency, and stakeholder input, limiting their usefulness for policy development and long-term cultural management. Moreover, in the digital age, the need for systematic and strategic data collection has become increasingly urgent. Without an effective CIS and clearly defined datasets, local administrative organizations (LAOs) are unable to fully harness the potential of cultural capital to promote sustainable development.

Theoretical foundations highlight the importance of cultural capital in shaping economic and social hierarchies (Bourdieu, 1986), and its potential to be converted into economic value (Griswold, 2004). CIS have been acknowledged for their capacity to collect, store, and disseminate data relevant to community development (Toubekis et al., 2011). These systems integrate datasets such as statistical and socioeconomic information, community needs, residents’ opinions, and records of local activities and networks (Bunch, 1993; Department of Local Administration, 2019; Library of Congress, 2006; Lopez, 2015; Ozuomba et al., 2013; van der Waldt, 2019). Effective use of these datasets can enhance the representation of cultural heritage, promote conservation, and encourage community engagement (Hawkes, 2001). However, technical limitations such as incomplete or inaccurately stored data, redundancies, and inconsistencies continue to hinder the effectiveness of CIS (Auwattanamongkol, 2019; Little & Rubin, 2002).

In Thailand, most existing studies have focused on fragmented aspects of cultural capital, often prioritizing tangible assets without incorporating them into cohesive information systems (Boonto, 2025; Chansanam & Tuamsuk, 2022; Kwiecien et al., 2021; Nachom, 2018). Furthermore, previous research has largely failed to analyze the full range of necessary datasets or to involve community stakeholders in defining data parameters and content (Boonto, 2025; Nonthacumjane & Johansson, 2023). These gaps result in datasets that lack socio-cultural coherence and are inadequate for supporting strategic policy or planning.

This study aims to bridge the gap in cultural capital data management through the development of a comprehensive essential dataset for CIS. The specific objectives are: (1) to identify and define the key data categories required for the development of a CIS focused on managing cultural capital; (2) to assess the relevance and necessity of each data category through expert evaluation, particularly from individuals with practical experience in the use of cultural capital in communities; and (3) to propose a dataset that can be adopted by LAOs in Thailand to support cultural capital management and policy-making.

The study is expected to offer a clear dataset that can be used by LAOs to manage cultural resources more efficiently. It will provide local governments with a data-driven framework to guide the design of policies that effectively utilize cultural capital, and facilitate stronger engagement from community members in preserving and promoting cultural heritage. From an academic perspective, the research will contribute to closing existing gaps in the literature by presenting a comprehensive and integrated approach to cultural capital data management within the Thai context.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Grounded in theoretical frameworks and an extensive review of related scholarship, this study integrates perspectives from community informatics (CI) and cultural capital informatics, alongside an examination of the following datasets.

2.1. Community Informatics

CI refers to the use of information and communication technology (ICT) to promote community development and participation. It emphasizes accessing and utilizing data to address local issues while creating opportunities for social, economic, and cultural development. CI enhances opportunities for communities to participate in decision making and local development through accessible information sources and digital tools for data management. Additionally, it connects community members, fosters transparency in data governance, and improves access to critical information for decision-making to achieve sustainable local development (Grisales Bohorquez et al., 2022; Gurstein, 2007, p. 11; Mehra et al., 2017).

CI is a field of study focusing on the relationship between ICT design and local communities, as well as implementing ICT projects within communities. It highlights using ICT to develop economical, social, and culturally appropriate and sustainable technological solutions. The field emphasizes the needs and local data practices involved in driving positive social change alongside community stakeholders (Davis et al., 2016; Ozuomba et al., 2013; Stillman & Linger, 2009).

Bunch (1993) categorized CI into two main types: (1) survival information: data related to essential aspects of living, such as health, housing, and political rights, and (2) citizen action information: information that facilitates participation in social, political, and economic processes within the community. The roles of CIS include strengthening social capital and expanding interactions within communities through the development and use of ICT applications that meet the needs of community members. These systems also foster networks that help sustain local resources in a sustainable manner (Gurstein, 2007, p. 74-77). CIS plays a crucial role in enhancing quality of life and providing access to essential services, such as healthcare, education, and economic opportunities (Eze et al., 2021; Lippeveld, 2017).

Community data or community profiles are analyses and reports based on data collected through community surveys. They provide an overview of the community’s population, including various aspects such as community geographical area; population and household numbers; age and gender distribution; birth and death rates; income data and economic status; social/community needs; access to services; knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs; and understanding and attitudes of the population toward significant health issues impacting the community (OpenLearn Create, n.d.). Community profiles are seen as a comprehensive approach to gathering information about communities, particularly regarding community needs. They serve as a foundation for driving effective community change and development (van der Waldt, 2019).

From a review of literature related to the use of community data in the development of information systems, it was found that the types of data utilized vary based on the objectives of each system’s development. These objectives significantly influence the types and characteristics of required data. Additionally, the unique characteristics of each community, including its specific needs and challenges, determine the appropriate data to use, ensuring alignment with the reality and requirements of community users. Community data has been applied in developing models for studying the context of community development, cultural heritage conservation projects, and as a guideline for data experts and technology developers aiming to design technologies for local communities (Huang et al., 2024). Furthermore, it serves as a medium for disseminating information from LAOs, enabling both public and private organizations to utilize the data effectively. Table 1 (Bunch, 1993; Department of Local Administration, n.d.; Library of Congress, 2006; Lopez, 2015; Ozuomba et al., 2013; van der Waldt, 2019) illustrates examples of community data from various concepts, research, and foundational information that have been employed in developing information systems.

Table 1

Community data from literature reviews

| Sources | Bunch (1993) | Ozuomba et al. (2013) | Lopez (2015) | van der Waldt (2019) | Library of Congress (2006) | Department of Local Administration (n.d.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community data |

From the analysis of community data based on concepts, research, and foundational information from agencies utilizing community data for the development of information systems, community data can be classified into five groups as follows: (1) statistical data–This category includes population statistics, such as population size, gender distribution, age, marital status, education, employment, health, and housing (Bunch, 1993; van der Waldt, 2019); (2) socio-economic data–This category encompasses general information (geographical factors, community history, community structure, livelihoods, local institutions, and individuals), infrastructure and public utilities (education, access to public services, medical and public health services, disaster prevention and mitigation, community facilities, volunteer organizations, and recreational facilities), social information (religion, ethnic groups), economic information (average household income), environmental information, and financial and fiscal data (Bunch, 1993; Department of Local Administration, n.d.; 2019; Library of Congress, 2006; Ozuomba et al., 2013; van der Waldt, 2019); (3) local issues–This data reflects problems or critical issues in the community, such as unemployment, poverty, lack of educational opportunities, access to healthcare services, infrastructure problems, and transportation. These factors impact the quality of life of residents in the area. Such data can be obtained from reports by government and private agencies, as well as from surveys of local residents’ opinions (Bunch, 1993); (4) residents’ viewpoints and community needs–This data includes community members’ opinions about local situations and issues. It can be gathered through interviews, public meetings, opinion surveys, local media (e.g., letters to the editor or community newspapers), and discussions on social media platforms. It also includes other communication sources that reflect the views and needs of community members. This information is crucial for understanding the real needs of the community (Bunch, 1993; Ozuomba et al., 2013); and (5) activity and network information–This category involves online activities, social networks, shared content, and tourism sites (Library of Congress, 2006; Lopez, 2015).

2.2. Cultural Capital Information

Cultural capital is a concept used to study the foundation of communities built upon strength. The French sociologist Bourdieu (1986) defines cultural capital as resources accumulated within individuals, objects, and institutions, shaped and transmitted through educational systems. The result of this accumulation is “taste,” which helps to create social distinctions and sustain social classes. Griswold (2004) expands on Bourdieu’s concept, stating that culture can be viewed as a type of capital that can be accumulated and converted into economic capital. It influences perceptions, cultural tastes, and lifestyles. The Department of Cultural Promotion (2019) explains that cultural capital refers to the inheritance of cultural wisdom, which can be used to add value in creative industries, transforming it into goods or services with added value. The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (n.d.) categorizes cultural heritage into two types: (1) tangible cultural heritage, which includes movable cultural heritage, such as paintings, sculptures, coins, and manuscripts; immovable cultural heritage, such as monuments, archaeological sites, and other structures; underwater cultural heritage, such as shipwrecks, underwater ruins, and submerged cities; and (2) intangible cultural heritage, which includes oral traditions, performing arts, rituals, and other cultural expressions.

Cultural heritage information (CHI) refers to all information related to cultural heritage, including data on the heritage itself, its management, preservation, relocation, and the administration of institutions responsible for such heritage. CHI consists of resources with evaluated significance, such as ancient documents, photographs, and historical maps, which require proper storage and preservation to be passed on to future generations. CHI is classified into three main categories: (1) collection information, which involves data about heritage items such as museum objects and documents; (2) technical information, which includes data on technical activities such as conservation and exhibitions; and (3) administrative information, which encompasses data on the management of institutions responsible for heritage, such as policies and visitor statistics. This information is crucial for preserving and transmitting cultural heritage from one generation to the next (Chaichuay, 2018).

Currently, institutions providing cultural information services, such as libraries, archives, and museums, emphasize the development of information services to improve the efficiency of access, sharing, and analysis of cultural data. These efforts aim to facilitate the effective use of such data for education, research, and conservation purposes. Efforts to enhance these services take various forms, particularly in the development and application of metadata. For example, Salse et al. (2022) studied metadata structures in museums and university collections across 23 institutions in Spain and Europe. They found that museums employed a variety of metadata standards, including Categories for the Description of Works of Art (CDWA), SPECTRUM, ICCD, MuseumDat, VRA Core, and LIDO. However, many museums still use custom metadata structures to meet the specific needs of their organizations. Similarly, a study by Pandey and Kumar (2023) examined metadata element sets used for digital art objects in Indian museums. Among the five museums studied, art objects were categorized into 13 categories, with each category employing different metadata standards to describe the data. It is evident that libraries, archives, and museums adopt diverse metadata standards and preserve various types of resources, making it impractical to use a single metadata standard for all resource types. However, having robust metadata is crucial for dissemination. Therefore, organizations must select metadata standards appropriate to the resources they manage and prioritize their effective implementation.

From a review of literature on cultural data management, there have been efforts to develop metadata capable of comprehensively and thoroughly describing cultural heritage according to its type. Based on the classification of cultural heritage by UNESCO, cultural heritage can be categorized into two types: tangible cultural heritage and intangible cultural heritage, as outlined in Table 2 (Chansanam & Tuamsuk, 2022; Giannoulakis et al., 2018; Kwiecien et al., 2021; Nachom, 2018; Trust, 2024; Ye, 2023).

Table 2

Cultural capital information from literature reviews

| Cultural capital information | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible cultural capital | Intangible cultural capital | |||||||||

| Moveable/immoveable/underwater cultural heritage | Oral traditions & expression | Performing arts | Social practices, rituals & festival events | Knowledge and practices, concerning nature and the universe | Traditional craftsmanship | |||||

| Trust (2024) | Kwiecien et al. (2021) | Giannoulakis et al. (2018) | Chansanam & Tuamsuk (2022) | Nachom (2018) | Ye (2023) | |||||

|

Dance

Recording

3D Environment Dancer |

|

||||||||

| 31 Elements | 18 Elements | 21 Elements | 14 Elements | 15 Elements | 28 Elements | |||||

| 127 Elements | ||||||||||

2.3. Datasets

Datasets refer to collections of data organized into a structured format for practical use. These datasets often consist of interrelated data presented in an orderly manner, such as tables with rows and columns or files containing data in various formats, including text, numbers, images, or audio. Datasets can take many forms, such as tables, text files (e.g., CSV, JSON), or databases. A dataset typically includes multiple rows (records) and columns (attributes or fields) that store related information. In the fields of data science and data analysis, datasets serve as critical resources for researchers and analysts to process, summarize, predict, and create data analysis models (databricks, n.d.; Kelleher & Tierney, 2018).

Datasets in research and data analysis can be categorized into several types based on the characteristics of the records and the types of variables that make up the dataset (Auwattanamongkol, 2019, pp. 10-11). For example: (1) record data refers to a dataset consisting of individual records, each with attributes or characteristics (attributes) that have a defined number and type of data. Each record can be compared to a row in a database table, for instance, personal information, which may include variables such as ID number, name, address, etc. (2) A data matrix consists of records where all variables are numerical data (numeric). The dataset can be represented as a matrix, where each row represents one data instance or record. Each instance can be represented as a vector consisting of numerical values. The vector’s size depends on the number of variables in the record: for example, the proportion of ingredients in a food mixture. (3) Transactional data consists of a list of events or items that appear in each record, such as customer purchase data for each transaction. The number of events or items on each record may vary. (4) Document data consists of individual documents (e.g., text). Each record contains variables indicating specific features of the document, such as the frequency of certain words appearing in the document. These variables can help determine the content of the document. This type of data often is high and most of the variable values are zero (sparse high dimensional data). (5) Binary data consists of records where each variable can only have a value of 1 or 0, indicating whether a specific event or status has occurred. This type of data is often converted from transactional data, with many variables, most of which are zero. (6) Graph data consists of data in a graph structure, where each record represents information in the form of nodes and edges, for example, chemical molecular structure data or protein-related data. These structures tend to be irregular and unpredictable. (7) Sequence data consists of a series of events or items occurring in sequence, such as gene sequences in chromosomes or web page visits within a certain time frame. This type of data reflects the occurrence of events in meaningful order. And (8) time series data consists of data where the variables change over time, such as daily stock indices or daily temperatures throughout the year. This type of data is related to time periods and temporal changes (databricks, n.d.; Khan & Hanna, 2022).

The use of datasets in research is diverse and highly beneficial across many disciplines, such as medicine, marketing, education, finance, and social sciences. Utilizing datasets for analysis can help identify relationships, predict outcomes, and make data-driven decisions based on sound principles. Example include analyzing basic datasets to develop a system for linking family medicine data (Saensrisawat et al., 2024), or developing a dataset on patients with heart disease symptoms to train a model for predicting heart disease risk using various techniques, such as machine learning (Janosi et al., 1989). However, the use of datasets also comes with several limitations that may impact on the quality of analysis and data handling. These limitations may arise from incomplete or improperly stored data that does not meet the user’s needs, such as incorrect, incomplete, redundant, or inconsistent data (Auwattanamongkol, 2019; Little & Rubin, 2002). Users of datasets may apply different techniques to prepare the data for more efficient and accurate analysis or model creation—for instance, using a data dictionary to explain the details of each field in the dataset, such as field names, data types, or descriptions. A data dictionary is a set of names, definitions, and characteristics of data elements used or collected in a database, information system, or research project. It explains the meaning and purpose of data elements in the context of the project while providing guidelines for interpreting and displaying the data. Additionally, the data dictionary includes metadata to define the scope, nature, and rules for using data elements, which helps reduce inconsistencies within the project, sets common standards, ensures consistency in data collection and use among research team members, facilitates data analysis, and establishes standards for data management. This makes it easier for users or programmers to understand and manage the dataset effectively (UC Merced Library, n.d.).

The management of cultural data in Thailand, despite efforts from various agencies to create databases and collect information, still faces challenges. A case study by Boonto (2025) on the development of digital cultural heritage management in local museums in Chiang Mai aimed to examine the lessons learned from managing and digitizing cultural heritage data using the Navanurak and Museum Pool platforms. The study also aimed to explore the development of digital cultural heritage data management for local museums in Thailand. The findings revealed that the studied area has a strong community network and is effectively able to connect museums with cultural tourism in the community. However, the data stored in the system primarily focuses on museum objects. The planning for data management from the initial stages of museum establishment lacked a systematic approach to storing cultural heritage data, such as the absence of an object register. This has resulted in challenges in the management and digitization processes, as there is a lack of necessary data in both the overall context and the specific context of each object. Furthermore, the absence of a connection between the object data and local community data has led to information that does not fully reflect the realities of the area or carry cultural significance in an authentic way (Boonto, 2025).

Studies on the role of LAOs in cultural capital information management reveal that LAOs have legal responsibilities for promoting and preserving local cultural heritage. Cultural operations typically fall under the purview of educational personnel who may lack specialized expertise in cultural management, resulting in unsystematic cultural information management. Consequently, most cultural data remains scattered and outdated. The cultural capital in the studied areas can be categorized into tangible and intangible assets, as well as policy-related information and administrative data. The research indicates that while LAOs have formal mandates for cultural preservation, the implementation of systematic cultural information management remains challenging due to the absence of systematic practices for data management. Despite these limitations, local cultural information management practices show promise in fostering educational opportunities, enhancing community engagement, and contributing to sustainable cultural conservation efforts (Anontachai et al., 2025).

Another study by Nonthacumjane and Johansson (2023) on shaping local information in Thailand identifies key issues in the digitalization of local information within the Provincial University Library Network (PULINET). These include contradictions in the conceptualization of local information among group members and the definitions established by the group. Additionally, there is a misalignment between the conceptual view of local information as a dynamic resource and the actual digitalization activities, which focus on formal boundaries and prominent objects, thus undermining the diversity and contextual richness of local information. The study also highlights the exclusion of marginalized groups and expressions that are not deemed socially acceptable. Furthermore, these contradictions are not leveraged as opportunities for learning and development but are instead concealed and resisted, preventing the full potential of local information digitalization from being realized (Nonthacumjane & Johansson, 2023).

Building upon the aforementioned research, the review of relevant studies underscores key challenges in the management of cultural heritage and local information in Thailand. These challenges include the absence of systematic data storage, the fragmentation of data across different sources, and the lack of comprehensive data management frameworks that encompass both tangible and intangible cultural heritage. Furthermore, there is a notable deficiency in the diversity and contextual richness of local information. Developing datasets for a community cultural capital information system is essential for effectively linking museum data with community information. By constructing datasets that integrate cultural heritage and local administrative data while reflecting cultural diversity, these efforts can address the identified challenges and foster systematic data management, thereby facilitating sustainable cultural development and preservation at the local level.

In this research, the authors studied and analyzed standards for storing various types of data, including those used for managing community and cultural heritage data. This includes the CDWA standard for tangible cultural heritage data and research that developed metadata for intangible cultural heritage data, to analyze the necessary information for managing cultural heritage. They then developed a dataset using a data dictionary as a tool to manage and explain the data, such as field names, data types, data definitions, and related rules. This helps clarify the meaning of the data, reduces confusion, and ensures that data usage is organized and understood consistently.

2.4. Research Conceptual Framework

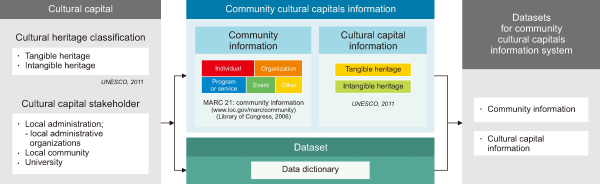

From an analysis of previous studies and literature, the researchers have established a research conceptual framework based on relevant concepts, theories, and related studies, including CI, cultural capital information, and datasets, as illustrated in Fig. 1 (Library of Congress, 2006; UNESCO, 2011).

Fig. 1

Research conceptual framework. MARC, machine readable cataloging; UNESCO, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

According to Fig. 1 (Library of Congress, 2006; UNESCO, 2011), CI is a concept that focuses on utilizing ICT to strengthen communities in areas of development, learning, and network connectivity. Cultural capital information, on the other hand, refers to data related to cultural capital, which reflects the knowledge, wisdom, beliefs, and identity of the community. When integrated with systematically collected datasets, this information can be analyzed to provide a clearer and more comprehensive understanding of the community’s overall picture and context. In developing the research conceptual framework, the researchers link the relationships found in the literature, beginning with the overarching concept of CI, proceeding in-depth into cultural capital information as a key data component that should be documented, employing datasets as tools for data collection, analysis, and transformation into new knowledge. These elements are interconnected in a systematic sequence, progressing from concept to practice and leading to the design of a clear and structured research conceptual framework.

3. RESEARCH METHOD

This study is part of a research project titled “Community Information System for Managing Cultural Capitals for Sustainable Development.” The specific objectives are: (1) to identify and define the key data categories required for the development of a CIS focused on managing cultural capital; (2) to assess the relevance and necessity of each data category through expert evaluation, particularly from individuals with practical experience in the use of cultural capital in communities; and (3) to propose a dataset that can be adopted by LAOs in Thailand to support cultural capital management and policy-making. The research process comprises three main stages, as outlined below.

3.1. Formulating of the Research Topic

The researchers identified a topic that is both pertinent and significant to the study’s objectives, emphasizing the analysis of key datasets essential for the development of a community cultural capital information system. The objective is to acquire datasets that are comprehensive, clear, and conducive to the efficient management of cultural capitals, thereby fostering sustainable development at both local and national levels. Based on the objectives of the study, the research questions can be identified as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Research objectives and research questions

| Research objectives | Research questions (RQ) |

|---|---|

| (1) To identify and define the key data categories required for the development of a CIS focused on managing cultural capital |

RQ1: What “community data” is necessary to be collected for the benefit of utilizing community data? RQ2: What “cultural capital data” is necessary to be collected for the benefit of utilizing cultural capital data? |

| (2) To assess the relevance and necessity of each data category |

RQ3: What is the level of necessity for using community data? RQ4: What is the level of necessity for using cultural capital data? |

| (3) To propose a dataset for the development of a CIS focused on managing cultural capital |

3.2. Research Design

In designing the research process, the researchers established a framework and methodology that aligns with the objectives of the study, taking into account relevant elements such as theories, concepts, requirements, and related experiences. This approach ensures that the study is comprehensive and capable of addressing the research questions effectively. Additionally, the researchers defined a structured and standardized research framework and plan to ensure that the research process leads to accurate, reliable, and valid results. The details of the research design and process are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4

Summary of research design and process

| Research objectives | Methodology/approach | Data sources/informants |

|---|---|---|

| 1. To identify and define the key data categories required for the development of a CIS focused on managing cultural capital | Policy documents, academic research, and existing cultural metadata | |

| 2. To assess the relevance and necessity of each data category | Six experts who are directly involved in the use of community cultural capital data | |

| 3. To propose a dataset for the development of a CIS focused on managing cultural capital |

3.3. Designing the Structure of Datasets to Identify and Define Key Data Categories

To fulfill the objective of identifying and defining the key data categories required for the development of a CIS focused on managing cultural capital, the researchers conducted a systematic process of dataset structuring. This process aimed to ensure that all essential data related to both community and cultural capital were clearly categorized and appropriately defined. The steps are outlined as follows.

3.3.1. Identification of Data Components

Based on document analysis and field data, the researchers compiled and listed essential data elements relevant to cultural capital and community context. This resulted in two primary data categories: Community data with 117 elements, and cultural capital data with 127 elements.

3.3.2. Analyzing and Grouping Data Components

After identifying the data components, the researchers analyzed their importance based on their relevance to practical applications. The components were then grouped based on concepts derived from the literature and related research:

• Community data: Sub-categorized into basic information about local government organizations (LGOs) responsible for the area and fundamental community data.

• Cultural capital data: Divided into two types—tangible and intangible cultural capital data.

The names and definitions of data elements were refined to ensure clarity and maintain the original meaning of all relevant components.

3.3.3. Adopting Metadata Standards

Based on literature and related research, researchers selected metadata standards as a framework for describing the data, including:

• Community information standards: Using the machine readable cataloging (MARC) format, specifically MARC 21 for community information, designed to systematically link community services data. MARC 21 is used to document non bibliographic resources meeting community information needs. Its scope includes individuals, organizations, programs or services, events, and others. This was combined with essential community data and basic LGO data.

• International metadata standards for museums: For instance, CDWA was used to describe cultural documents and objects. The researchers also designed datasets related to traditions, culture, and local wisdom, adapting metadata from relevant research.

3.3.4. Knowledge Integration

The researchers studied and analyzed content from documents, manuals, and research related to arts, culture, and local wisdom. They also interviewed individuals involved in utilizing cultural capital data in the community. The interviews focused on identifying necessary cultural capital data for practical use, which served as a guideline for dataset development.

3.4. Evaluation and Refinement of the Dataset

In the final stage, the researchers evaluated the information derived from the previous stages to determine which data is essential for future development or research. This evaluation process involved additional interviews with experts to arrive at more definitive conclusions.

3.4.1. Expert Evaluation

The evaluation and refinement of the cultural capital dataset for sustainable development were conducted by experts selected through purposive sampling. These experts were individuals directly involved in using community cultural capital data and were divided into four groups: (1) Cultural practitioners in LGOs; (2) Data experts familiar with dataset structuring and management; (3) Experts in arts, culture, and local wisdom; and (4) Cultural data users for work, education, or research purposes. The number of experts participating in the study ranged from 6 to 12, which is consistent with the recommendations of Guest et al. (2006), who suggested that data saturation typically occurs within 6 to 12 interviews. Interviews continued until no new significant themes emerged from the data, a phenomenon known as thematic saturation. This ensures that the data collected is rich and comprehensive enough to effectively address the research questions. The selection of the number of experts also aligns with the approach suggested by Malterud et al. (2016), who recommended that the sample size be determined based on “information power,” which refers to the number of interviews required to provide sufficient data to answer the research questions. Information on the key informants is presented in Table 5.

Table 5

Information on the key informants

| Group of key informants | Qualifications | Work experience | Number of people (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Cultural practitioners in local government organizations in Roi Et | Executive or cultural practitioner in local government organizations in the study area, Roi Et province | At least 3 years of experience | 2 |

| 2) Data experts | Individuals with work experience or research related to community data or cultural arts and local wisdom | At least 3 years of experience | 2 |

| 3) Experts in cultural arts and local wisdom | Recognized experts in cultural arts and local wisdom with work experience or research related to the field | At least 3 years of experience | 1 |

| 4) Users of cultural data for work, education, or research | Individuals using cultural data for work, education, or research | At least 3 years of experience | 1 |

3.4.2. Research Tools

The research utilized interview guidelines with questions aligned to the study’s objectives, focusing on essential community and cultural capital data required for practical applications, and the level of necessity for community and cultural capital data. Data collection involved in-depth interviews conducted by the researchers from July to August 2024 over a two-month period.

3.4.3. Data Analysis

The data analysis in this study employed content analysis methods, which involve categorizing, analyzing, and describing the data based on key themes that align with the research objectives. The data obtained from the interviews were recorded in MS Word. Subsequently, the researchers coded the data by assigning codes to sentences or paragraphs that were considered significant. This coding process facilitates the efficient extraction of information relevant to the research questions. This includes the coding of conceptual variables, grouping of terminology, analysis of relationships, and identification of key themes for further study. For example, an interview question regards the cultural capital data necessary for collecting information for the benefit of using community data (QA1: “What ‘cultural capital data’ is necessary to be collected for the benefit of using community data?”).

The data coding process begins prior to data collection by creating initial code based on the established theoretical framework. Subsequently, these codes are revised and updated to more appropriate ones, with some irrelevant codes discarded. These codes are assigned meanings and recorded in the field notes. Once the data or groups of terms are categorized, the next step is to identify relationships and assign codes according to the examples in the data classification table. This process ensures that the analysis can be conducted effectively and accurately. An example is illustrated in Table 6.

Table 6

Data classification for cultural capital

| Data record | Code group | Concomitant relationships | Key terms |

|---|---|---|---|

| “When designing a cultural capital exhibition, it’s important to consider the necessary data based on the specific themes or objectives of the display. For example, if the goal is to showcase the production process of cultural capital, relevant data related to that process should be used. Or, if the focus is on the origins of cultural capital, historical data will be essential. Additionally, the characteristics of the objects being displayed must be taken into account, such as their size, shape, weight, source, and preservation methods. Information on the history, significance, and usage of cultural capital within the community, along with its connection to places and traditional technologies, should also be included. All of this data will help in designing an exhibition that effectively tells a story and determines the optimal layout of the display space.” | is part of | Cultural capital |

After the researchers collected and refined the preliminary data, these data were summarized and analyzed in alignment with the research objectives using two methods of analysis: descriptive analysis and content analysis. Descriptive analysis was employed to provide an overview of the fundamental characteristics of the data, while content analysis was used for in-depth examination by categorizing and interpreting the data to extract key findings and conclusions. The results of the data analysis were presented in tabular form to systematically display the key information and research findings. The analysis was explained using descriptive methods to ensure clarity in the presentation of the data and commentary. The combination of both methods will enhance the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the analysis, facilitating effective communication of the research findings in a clear and accessible manner.

The researchers further examined and synthesized content from documents, textbooks, manuals, and research related to cultural arts and local wisdom. This helped design the structure of the community dataset and the cultural capital data that need to be collected for practical use. The researchers then asked the experts to assess the necessity level of the community and cultural capital data once again, in order to prioritize or measure the importance of these data. This process contributed to obtaining more diverse and comprehensive results.

To evaluate the necessity level of community and cultural capital data, a 5-point rating scale was employed, ranging from most necessary, very necessary, moderately necessary, slightly necessary, to least necessary. The calculation approach involved using the average scores from the ratings provided by each expert group. Software such as Excel was used to compute the average and determine the frequency for statistical analysis.

4. RESEARCH RESULTS

4.1. Community Datasets Required for Developing CIS

The analysis of the community data required for collection, as identified by six experts, reveals the essential data to be collected in common, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7

Community data

Case A-F refers to the identification codes of the experts who provided the information during the interviews. These codes are used to reference the experts involved in each case. Check mark (✓) indicates that an answer related to the specific issue was found from the interview with the respective expert. Cross mark (✗) indicates that no answer related to the specific issue was found from the interview with the respective expert.

Based on Table 7, the community data required for collection and utilization consists of the following categories.

1) Spatial information, including geographic data, economic data, social data (such as community groups and social organizations), and cultural data (local traditions and customs, religious activities and beliefs, and local wisdom holders).

2) Community organization information, comprising (1) core function organizations, which are the primary government agencies directly responsible for the area, such as LAOs (subdistrict administrative organizations, subdistrict municipalities, etc.), and (2) area function organizations related to the community, which may include public agencies, private organizations, civil society groups, and community-based organizations.

3) Community capital and potential information, including data on individuals, groups, agencies, organizations, local resources, and both physical and social infrastructure.

4) Information for development and construction purposes, such as data on building locations, surrounding environments, site accessibility, boundary definitions, budget allocation, and the specific needs of the community (e.g., for establishing community museums).

The analysis of cultural capital data required for collection and utilization, based on the perspectives of six experts, indicates that the necessary data to be collected are consistent across all experts, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8

Cultural capital data

| Cultural capital data | Case | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | ||

| 1. Tangible cultural capital, such as historical sites and artifacts | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 |

| 2. Intangible cultural capital, such as traditions, craftsmanship, and local arts | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 |

| 3. Potential benefits for extension in commerce, careers, education, or other areas | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 2 |

| 4. Natural heritage, such as landscapes, natural tourist attractions, and native flora and fauna | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 |

| 5. Information on individuals involved in cultural heritage, such as cultural experts, key persons and successors | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 |

| 6. Information on cultural management and support, such as conservation, restoration, promotion, dissemination, financial support, and policy | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 |

| 7. In-depth data collection details (for reference purposes), such as historical data from official records, community legends, and oral histories from local wisdom keepers (key persons) | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 |

| 8. Community valuation of cultural capital in various dimensions, including belief systems and the relationship between cultural capital and the community | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 |

Case A-F refers to the identification codes of the experts who provided the information during the interviews. These codes are used to reference the experts involved in each case. Check mark (✓) indicates that an answer related to the specific issue was found from the interview with the respective expert. Cross mark (✗) indicates that no answer related to the specific issue was found from the interview with the respective expert.

From Table 8, it was found that the cultural capital data required for collection and utilization consists of the following:

1) Tangible cultural capital, such as historical sites, monuments, and artifacts.

2) Intangible cultural capital, including traditions, local craftsmanship, and folk arts.

3) Information on individuals involved in cultural heritage, such as key cultural figures, experts, and successors.

4) Detailed in-depth information for reference purposes, including historical records from government sources, community legends, and oral histories from local wisdom keepers.

5) Natural heritage, such as landscapes, natural tourist attractions, and native plants and animals.

6) Information on cultural management and support, such as conservation, restoration, promotion, dissemination, financial assistance, and policy support.

7) Community valuation of cultural capital in various dimensions, which may include belief systems related to the cultural capital and its relationship with the community.

8) Potential benefits for extension and application, including commercial, professional, educational, or other uses.

Results of the development and evaluation on the necessity level of the 15 community datasets revealed that four datasets were rated as most necessary for the CIS for managing cultural capital, as follows: Individual data (e.g., community leaders/local scholars) ( =4.69); Organizational data ( =4.63); Area context data–community history ( =4.50); and Community map data ( =4.50). The remaining 11 datasets were rated as very necessary, including: Community location data ( =4.48); Local project data ( =4.42); Local personnel data ( =4.36); LAO data ( =4.31); Area context data–population size ( =4.30); Activity data ( =4.22); Program or service data ( =4.20); Area context data–area size and administrative boundaries ( =4.61); Community slogan data ( =3.92); and Budget management data ( =3.67), respectively. In total, the 15 community datasets are comprised of 117 data elements. The required community datasets are presented in Table 9.

Table 9

Community datasets required for developing a community cultural capitals information system

| No. | Community datasets | Number of data elements | Means | Necessity level | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Administrative Organization (LAO) data: LAO code; LAO name; LAO type; house number; street name; village name; subdistrict name; district name; province name; postal code; location latitude; location longitude; Northern bordering; Southern bordering; Eastern bordering; Western bordering; responsibility area; historical background; geographical features; climatic conditions; LAO images; LAO website; contact information | 23 | 4.31 | Very necessary | 0.63 |

| 2 | Budget management data: Budget code; budget name; budget type/category (categorized according to relevant laws) | 3 | 3.67 | Very necessary | 1.54 |

| 3 | Local project data: Project code; budget name; project name; plan code; plan volume; plan page; ordinance/regulation code; ordinance/regulation volume; ordinance/regulation page; department code; LAO code; LAO name; project type | 13 | 4.42 | Very necessary | 0.76 |

| 4 | Local personnel data: Citizen ID number; first name; last name; title; gender; date of birth; education level; personnel type; position number; position name; term end date; personnel level; department code; department name; department type; LAO code; LAO name | 17 | 4.36 | Very necessary | 0.84 |

| 5 | Community location data: Community code; village number; village/community name; subdistrict name; district name; province name; latitude; longitude | 8 | 4.48 | Very necessary | 0.55 |

| 6 | Area context data: Community history: community history code; community history | 2 | 4.50 | Most necessary | 1.01 |

| 7 | Area context data–Area size and administrative boundaries: area code; Northern boundary; Southern boundary; Eastern boundary; Western boundary; topographical features; administrative divisions (or community/village names within the administrative area); area size (sq. km.); transportation and accessibility (e.g., public transport routes) | 9 | 3.96 | Very necessary | 0.92 |

| 8 | Area context data–Population: Area code; male population; female population; number of households; primary, secondary, and supplementary occupations | 5 | 4.30 | Very necessary | 0.73 |

| 9 | Community slogan data: Slogan code; community slogan | 2 | 3.92 | Very necessary | 1.13 |

| 10 | Community map data: Map code; community map | 2 | 4.50 | Most necessary | 1.01 |

| 11 | Individual data (e.g., community leaders or local scholars): Individual code; name; address; phone number; expertise; notes | 6 | 4.69 | Most necessary | 0.55 |

| 12 | Organization data: Organization code; organization name; organization address; phone number; fax number; email address; location; operating hours; specific information/facilities/services provided | 9 | 4.63 | Most necessary | 0.55 |

| 13 | Program or service data: Service code; service name; service provider; location; specific information/facilities/services provided | 5 | 4.20 | Very necessary | 0.69 |

| 14 | Activity data: Activity code; activity name; activity venue; date; time; responsible person; notes on funding source; budget; activity details (1.07) | 9 | 4.22 | Very necessary | 0.88 |

| 15 | Other data may involve community-related operations and consists of 4 data elements: Data code, data name, data address, notes | 4 | 3.58 | Very necessary | 1.07 |

| Total number of data elements | 117 |

4.2. Cultural Capital Datasets Required for Developing CIS

Results of the development and evaluation of the necessity level of the cultural capital datasets revealed that among the two main datasets, intangible cultural datasets were rated at the most necessary level ( =4.4.64), while the tangible cultural dataset was rated at a very necessary level ( =4.37) for the CIS for managing cultural capital. For the intangible cultural datasets, they are divided into five subsets. It is revealed that all five subsets were rated at the most necessary level, respectively, as follows: Traditional craftsmanship data ( =4.74); Social practices, rituals, and festivals data ( =4.73); Performing arts data ( =4.61); Knowledge and practices related to nature and the universe data ( =4.61); and Narrative data ( =4.53). In total, the two cultural capital datasets comprise 124 data elements. The required community datasets are presented in Table 10.

Table 10

Cultural capital datasets required for developing a community cultural capitals information system

| No. | Cultural capital datasets | Number of data elements | Means | Necessity level | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tangible cultural heritage data (in referenced to CDWA Standards): Type and quantity of work; classification, name; creation; form of the work, dimensions; materials used in creation; marks or inscriptions on materials; relationships among multiple created works; edition; construction methods or specific techniques used; description of display or presentation methods; description of the work’s appearance; physical condition assessment; conservation or restoration; artistic subject matter; object context; descriptive text or explanation of the work; critical commentary on the work; related artworks or architecture; current location and geographic location of the artwork or architecture; individuals or groups holding usage, display, or reproduction rights; provenance or ownership history from creation to present; exhibition or loan details; documentation of creation and description modifications; related documentation; references to textual sources related to the artwork or architecture; information about artists, architects, or other relevant individuals; information about geographical locations significant to the artwork, architecture, or creator; general concepts necessary for cataloging or describing the work (e.g., object type, materials, activities, styles); information about characters, animals, themes, stories, literature, myths, religions, or historical or fictional events mentioned by name | 31 | 4.37 | Very necessary | 0.58 |

| 2 | Intangible cultural heritage data | 93 | 4.64 | Most necessary | 0.49 |

| 2.1 | Narrative data (e.g., folk legends - oral tradition & expression) consists of 17 data elements: Identifier; name; creator; contributors; description; keywords; characters; morals; ethnic group; location; relationships; country; language; media; sources; date; rights | 17 | 4.53 | Most necessary | 0.53 |

| 2.2 | Performing arts data consists of 20 data elements: Name; history; country/region of origin; time of origin; dance styles; musical concepts; lyrics; dance annotations; description; GPS coordinates; performance duration; software; location; objects and descriptions; explanations; gender; facial expressions; traditional costume description; number of performers+performer attributes | 20 | 4.61 | Most necessary | 0.45 |

| 2.3 | Social practices, rituals, and festivals data consists of 13 data elements: Tradition/local name; month of celebration; frequency/scale of event; lunar calendar; purpose; activities; rituals; literature; beliefs; location; participants; equipment; buildings | 13 | 4.73 | Most necessary | 0.45 |

| 2.4 | Knowledge and practices related to nature and the universe data consists of 15 data elements: Title of the work; work code; creator; description; language; ethnicity; date and time; supplementary media; keywords; copyright owner; habitat/location; categories of cultural and intellectual knowledge; Thai name; English name; local name | 15 | 4.61 | Most necessary | 0.55 |

| 2.5 | Traditional craftsmanship data consists of 28 data elements: Name; keywords; craft code; category; owner; executor; affiliated nation; generational age; production area; modeling; dimensions; weight; color; design; materials; process forms (production process); ornaments; physical qualities and evaluation; user groups; usage occasions; cultural implications; technology level; values; rights; data collectors; time of data collection; physical storage location; image storage location | 28 | 4.74 | Most necessary | 0.47 |

| Total number of cultural capital data elements | 124 | ||||

5. DISCUSSION

The findings of this research on developing a community cultural capital information system underscore the critical importance of structured data management in nurturing local cultural assets, aligning closely with the principles of CI as discussed in the literature. As noted by Gurstein (2007), CI emphasizes the role of ICT in fostering community participation and development. Our study’s qualitative approach, engaging local cultural practitioners and experts, embodies this principle by grounding the developed datasets in the lived realities and needs of the community.

The delineation of community data and cultural capital data reflects the theoretical framework established in the literature, which identifies various dimensions of cultural capital, including tangible and intangible aspects (Bourdieu, 1986; Griswold, 2004). In this study, the categorization into intangible cultural capitals information, tangible cultural capitals information, and administrative cultural capitals information mirrors the need for a multifaceted understanding of cultural resources, as identified in earlier research. This classification allows for nuanced data analysis that can directly inform policy making and community initiatives aimed at sustainable development, resonating with the findings of UNESCO (2011) regarding the preservation of cultural heritages’ importance.

Moreover, the study supports the assertion that the effective management of cultural capital contributes to social cohesion and local economic development, which has been a recurrent theme in the literature (Department of Cultural Promotion, 2019). The engagement of community members in the evaluation process not only enhances the relevance of the cultural capital datasets but also builds a participatory knowledge base, echoing the sentiments expressed by Auwattanamongkol (2019) on the significance of involving stakeholders in data governance and utilization.

The researchers designed a dataset for cultural capital aimed at sustainable development by applying international metadata standards for museums (CDWA) to describe cultural documents and objects related to tangible cultural capital. This was combined with the adaptation of metadata in related research for designing datasets on traditions, culture, and local wisdom, including (1) a Metadata construction scheme of a traditional clothing digital collection (Ye, 2023); (2) Development of Thai culture ontology-based metadata: Heet Sib Song (Chansanam & Tuamsuk, 2022); (3) a Metadata schema for folktales in the Mekong River Basin (Kwiecien et al., 2021); (4) Metadata for intangible cultural heritage - the case of folk dances (Giannoulakis et al., 2018); and (5) Local culture and wisdom metadata (Nachom, 2018). Our application of these metadata standards, utilized to structure the datasets, resonates with the literature’s recommendation for clear data categorization to enhance accessibility and usability (Toubekis et al., 2011). By integrating these standards, the research ensures that essential cultural and community data can be effectively shared and operationalized across various platforms, thereby enhancing transparency and fostering collaborative approaches to cultural capital management.

While the primary focus of this study is on Thailand, the proposed dataset framework and CIS model offer valuable insights that may inform similar efforts in other contexts. By enabling LAOs to systematically manage and utilize cultural capital, the study provides a scalable approach that could inspire regional and national strategies for cultural heritage preservation and policy development. However, it is important to recognize that cultural capital is inherently shaped by unique historical, social, and cultural contexts. As such, while the structure and methodology of the dataset may be adaptable, its direct application in other countries would require careful contextualization to reflect local cultural norms, values, and institutional frameworks. This highlights the importance of flexibility and cultural sensitivity when transferring or scaling such systems beyond their original setting.

6. CONCLUSION

This study presents a foundational framework for the development of essential datasets to support a CIS in Thailand. The research underscores the value of integrating community data with cultural capital data to enable more effective and context-sensitive management of cultural assets. By structuring these datasets, community data, and cultural capital data, the study provides a practical tool that can be employed by local government agencies, cultural practitioners, community members, and policymakers to inform decision-making, resource allocation, and local development planning.

Key findings highlight the importance of a dual-data approach: Community data offers insight into demographic, social, and economic characteristics, while cultural capital data documents heritage, traditions, and other local cultural assets. The integration of these data types enhances the ability of stakeholders to design development projects that are aligned with local values and conditions, supporting sustainable growth and cultural conservation. Furthermore, the inclusion of metadata standards facilitates data interoperability across platforms, fostering inter-community collaboration and the dissemination of best practices.

The research also affirms the central role of cultural capital in advancing sustainable development and social cohesion, particularly in the context of increasing globalization. By adopting a data-driven approach to cultural resource management, communities can strengthen local identity, increase participation in cultural initiatives, and build resilience against external pressures. This study contributes to the broader discourse on CI and cultural capital by bridging theoretical frameworks with practical implementation strategies. It offers empirical evidence supporting the use of structured data in strengthening local governance and cultural sustainability.

To maximize the impact of this research, it is recommended that LAOs and cultural institutions adopt and apply the proposed dataset structure. Capacity-building initiatives, such as training programs for community stakeholders, should be developed to ensure effective data collection, interpretation, and application. In addition, continuous monitoring and evaluation of the CIS should be undertaken to ensure its relevance and responsiveness to evolving community dynamics.

Future research should examine the long-term outcomes of implementing CIS frameworks, with particular attention to their influence on community development, policy integration, and cultural vitality. Studies could also explore the role of digital technologies—such as mobile applications, geospatial mapping, and participatory platforms—in enhancing the accessibility and utility of cultural data. Lastly, while this study is contextually grounded in Thailand, future comparative research could investigate the adaptability of the framework in other cultural settings, taking into account local variations in social structures, governance systems, and cultural values.

The limitations of this study include the limited scope of community data collection, where certain groups may not have participated in providing information, resulting in data that does not fully reflect the actual needs of the community. The cultural diversity of each community poses challenges in developing a data structure that comprehensively covers all aspects. Furthermore, stakeholder participation may be incomplete, affecting the practical application of the data as expected. Additionally, technological limitations, such as a lack of modern technology or insufficient training in certain areas, may hinder the appropriate use of data management systems within the context of each community.

REFERENCES

, , (2025) Cultural capital information management and sustainability in the context of Thailand local government organizations Journal of Posthumanism, 5, 117-137 https://doi.org/10.63332/joph.v5i3.717.

, (1986) Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education Greenwood The forms of capital, pp. 241-258, https://home.iitk.ac.in/~amman/soc748/bourdieu_forms_of_capital.pdfArticle Id (other)

(2018) Cultural heritage information: Concept and research issues Journal of Information Science Research and Practice, 35, 130-153 https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jiskku/article/view/108375. Article Id (other)

, (2022) Development of Thai culture ontology-based metadata: Heet Sib Song (Twelve Months Festival) Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Studies, 22, 725-737 https://doi.org/10.14456/hasss.2022.62.

databricks (n.d.) What is a dataset? https://www.databricks.com/glossary/what-is-dataset Article Id (other)

, , , , , (2016) Handbook of research on comparative approaches to the digital age revolution in Europe and the Americas IGI Global Scientific Publishing The geography of digital literacy: Mapping communications technology training programs in Austin, Texas, pp. 371-384, https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-8740-0.ch022 Article Id (pmcid)

Department of Cultural Promotion (2019) Culture, value to value https://www.culture.go.th/culture_th/ewt_news.php?nid=3972&filename=index Article Id (other)

Department of Local Administration (2019) [User manual for the local administration organizations system] Thai. https://www.nongkratumkorat.go.th/pdf/16464852061.pdf Article Id (other)

Department of Local Administration (n.d.) Public health and environment https://info.dla.go.th/onepage/info07.jsp Article Id (other)

, , (2021) Community informatics for sustainable management of pandemics in developing countries: A case study of COVID-19 in Nigeria Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, 16, 100632 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemep.2021.100632. Article Id (pmcid)

, , (2018) Metadata for intangible cultural heritage - the case of folk dances Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications, 5, 634-645 https://doi.org/10.5220/0006760906340645.

, , (2022) How librarians and firefighters built a special library in Champaign, Illinois, USA: A community informatics story Digital Transformation and Society, 2, 42-59 https://doi.org/10.1108/dts-08-2022-0035.

, , (2006) How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability Field Methods, 18, 59-82 https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903.

(2007) What is community informatics (and why does it matter)? Polimetrica. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.0712.3220

(2001) The fourth pillar of sustainability: Culture's essential role in public planning Common Ground Publishing https://www.culturaldevelopment.net.au/downloads/FourthPillarSummary.pdf Article Id (other)

, , , , , (2024) A community information model and wind environment parametric simulation system for old urban area microclimate optimization: A case study of Dongshi Town, China Buildings, 14, 832 https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14030832.

, , , (1989) Heart disease https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/heart+disease Article Id (other)

, (2022) The subjects and stages of ai dataset development: A framework for dataset accountability https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4217148

, , , , (2021) Metadata schema for folktales in the Mekong River Basin Informatics, 8, 82 https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics8040082.

Library of Congress (2006) MARC 21 community information https://www.loc.gov/marc/community/ciintro.html Article Id (other)

(2017) Routine health facility and community information systems: Creating an information use culture Global Health: Science and Practice, 5, 338 https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00319. Article Id (pmcid)

, , (2016) Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power Qualitative Health Research, 26, 1753-1760 https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444.

, , , , (2017) Rural and small public libraries: Challenges and opportunities (Vols. Vol. 43) Rural librarians as change agents in the twenty-first century: Applying community informatics in the Southern and Central Appalachian region to further ICT literacy training, pp. 123-153, Emerald Publishing Limited

(2018) Local culture and wisdom metadata PULINET Journal, 5, 304-315 https://pulinet.oas.psu.ac.th/index.php/journal/article/viewFile/306/307. Article Id (other)

, (2023) Shaping local information in Thailand: Hidden contradictions in the digitisation activities of the Provincial University Library Network (PULINET) Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 55, 246-258 https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006221143101.

OpenLearn Create (n.d.) Health management, ethics and research module: 11. Developing your community profile https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=229 Article Id (other)

, , , (2013) Preliminary context analysis of community informatics social network web application Nigerian Journal of Technology, 32, 266-272 https://www.ajol.info/index.php/njt/article/view/123594. Article Id (other)

, (2023) A survey of the metadata element sets used for digital art objects in the online collections of the museums of India DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 43, 226-233 https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Survey-of-the-Metadata-Element-Sets-Used-for-Art-Pandey-Kumar/e954443a80a87a307d7eb50401b24059af958885. Article Id (other)

, , , , , (2024) Analysis of standard data sets to develop a family medicine data linkage system Thai Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 16, 941-953 https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/TJPP/article/view/263740. Article Id (other)

, , , , (2022) GLAM metadata in museums and university collections: A state-of-the-art (Spain and other European countries) Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 73, 477-495 https://doi.org/10.1108/gkmc-06-2022-0133.

, (2009) Community informatics and information systems: Can they be better connected? The Information Society, 25, 255-264 https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240903028706.

(2024) Categories for the description of works of art https://www.getty.edu/publications/categories-description-works-art/ Article Id (other)

UC Merced Library (n.d.) What is a data dictionary? https://library.ucmerced.edu/data-dictionaries Article Id (other)

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (n.d.) Cultural heritage https://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/cultural-heritage Article Id (other)

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2011) 2003 Convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/15164-EN.pdf Article Id (other)

(2019) Community profiling as instrument to enhance project planning in local government African Journal of Public Affairs, 11, 1-21 https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC-19603347f5. Article Id (other)

(2023) Metadata construction scheme of a traditional clothing digital collection The Electronic Library, 41, 367-386 https://doi.org/10.1108/el-01-2023-0004.