1. INTRODUCTION

The advancement of technology has resulted in the extensive use of electrical and electronic devices, leading to significant e-waste composed of metals, plastics, rubber, glass, and ceramics (Mat Nawi et al., 2024). Public organisations in Thi-Qar province, Iraq, generate significant amounts of e-waste annually, which is disposed of in landfills, resulting in the leakage of harmful chemicals (Alziady & Enayah, 2019). E-waste comprises hazardous materials such as lead, mercury, arsenic, cadmium, selenium, and chromium, complicating its disposal. Harmful metals are associated with malignancies, miscarriages, neurological damage, blood disorders, and dioxins that adversely affect the central nervous system (Regel-Rosocka, 2018). E-waste management in Iraq presents challenges due to environmental, technical, economic, and health factors during treatment and recycling processes, resulting in significant exposure to lead, mercury, cadmium, and arsenic. Public organisations in Thi-Qar generate significant amounts of e-waste due to increasing domestic wealth and declining product prices post-2003 (Ikhlayel, 2018). A communication and media commission indicated that these organisations acquired 695,000 computers in 2018, along with numerous electronic devices, including TVs, phones, DVD players, printers, satellite receivers, remote controls, mobile chargers, copy machines, lighting equipment, microwaves, ovens, air conditioners, and others on an annual basis (Mat Nawi et al., 2024). Cities produce a significant amount of electrical and electronic waste, one of the fastest-growing sources of waste. The disposal of abandoned devices poses significant environmental and health risks due to their complex composition of materials (Kumar et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2024).

Consequently, hazardous e-waste processing that poses risks to human health and the environment has raised concerns among federal governments, regulators, consumers, competitors, communities, environmental advocacy groups, business associations, researchers, and local authorities (Regel-Rosocka, 2018). Authorities have identified harmful compounds infiltrating the environment, resulting in city residents being exposed to elevated levels of lead, mercury, cadmium, and arsenic (Waghmode et al., 2021). The inadequate environmental disposal of e-waste by public organisations in Thi-Qar and the increasing volumes of e-waste constitute a significant concern. The increasing recognition of environmental degradation in recent years highlights the importance of e-waste disposal as a critical factor in attaining community satisfaction (Alziady, 2018). Recognizing the incentives that motivate organisational managers to manage e-waste environmentally is essential, particularly in regions such as Thi-Qar, where e-waste is increasing and environmental pressures are intensifying (Alziady & Enayah, 2019). Reducing e-waste accumulation enables an organisation to utilise resources more efficiently and recover secondary raw materials via recycling and other recovery methods, thereby enhancing its environmental performance throughout the product life cycle.

Public organisations have increasingly utilised electronic devices in the past decade, with newer and more powerful models replacing older versions. Consequently, numerous gadgets have a limited lifespan, making a significant quantity obsolete. E-waste generated from obsolete electronics is disposed of in landfills, posing risks to environmental integrity and human health (Ikhlayel, 2018). E-waste comprises hazardous substances that can harm the environment if not recycled properly. E-waste also comprises valuable metals such as iron, copper, aluminium, gold, and silver. To maximise resource efficiency, e-waste contains valuable raw materials (Borthakur & Govind, 2018). Administrators of public organisations must prioritise the environmental disposal of electronic waste. The issue of e-waste has heightened awareness. Methods for disposing of e-waste include reusing, remanufacturing, recycling, incineration, and landfilling (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017). This represents an innovative approach for organisations to adhere to environmental regulations. Public sector managers may leverage environmental knowledge to reconcile economic, social, and environmental performance.

The significant increase in e-waste in Thi-Qar prompts an examination of public organisation managers’ perspectives on environmental disposal and their willingness to implement appropriate e-waste management practices and disposal techniques. E-waste poses significant environmental pollution risks and potential health hazards. Consequently, managers’ perceptions regarding the hazardous nature of corporate e-waste may influence the relationship between institutional pressures and the inclination to dispose of e-waste in an environmentally responsible manner. A recent study from Iraq has highlighted a concerning situation (Mat Nawi et al., 2024). The quantity of discarded e-waste remains uncertain, necessitating further investigation into the environmental consequences of institutional pressures on managers’ intentions to dispose of e-waste in an environmentally responsible manner and the mediating influence of attitude. This study aims to analyse and understand the significant challenges associated with e-waste. The research structure includes the introduction, research question framework, objectives, theoretical background, methods, findings, discussion, and conclusions.

Post-2003, there was a global increase in economic development and public sector purchasing power, which led to a rise in the utilisation of computers, laptops, televisions, DVDs, printers, copy machines, and mobile phones. The volume of e-waste has significantly increased. Improper e-waste disposal, including municipal solid waste and open burning, has resulted in environmental pollution; however, informal recycling remains prevalent in cities. Consequently, numerous e-waste components are disposed of in open landfills and dumps. As a result, administrators of public organisations in Thi-Qar have acknowledged the gravity of e-waste and have indicated a commitment to its environmentally responsible disposal. Research indicates that institutional constraints, including coercive pressure, normative influence, and imitation, impact the adoption and dissemination of environmental practices among organisational managers (Lin & Ho, 2016). This present research investigates the impact of institutional factors on intention and attitude as mediating variables. The following questions are examined.

Do institutional influences impact public organisation managers’ willingness to dispose of e-waste in an environmentally responsible manner? Do the same institutional powers affect the adoption of e-waste? What is the role of attitude in mediating institutional pressures and the inclination of managers to dispose of e-waste in an environmentally responsible manner?

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

E-waste represents a multifaceted category of waste, characterised by its material heterogeneity and diverse product lifecycles. The challenge in identifying the material type and product lifecycle indicates that e-waste and its associated commodity chains are complex. After their useful life, electronics become e-waste. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identifies e-waste as used electronics, recognizing that recyclable products reduce improper disposal in unmanaged landfills. E-waste includes any electrical and electronic equipment dumped by the owner as garbage without purpose of reuse. Ananno et al. (2021) define e-waste as all non-recyclable electrical and electronic gadgets. Zhang and Xu (2016)’s study found that electronic gadgets include both harmful and valuable components, making recycling ecologically and economically beneficial (Zhang & Xu, 2016). E-waste disposal must reduce or eliminate hazardous materials such as lead, cadmium, mercury, hexavalent chromium, polybrominated biphenyls, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, arsenic, and polyvinyl chloride from electronic devices. Chemicals and metals disposed of in landfills or incinerated impair the environment and human health by contaminating water, air, soil, dust, and food (Ikhlayel, 2018). These materials carry health and environmental concerns, including water and soil contamination (Sharma et al., 2024). Research shows that e-waste also includes gold, palladium, silver, indium, and rare earth metals, making recycling more beneficial.

E-waste is one of the fastest-growing issues since typical product lifespans have shortened, leading to the dumping of outmoded technology into the waste stream (Sharma et al., 2024). E-waste is a major issue with potentially serious repercussions. According to Zhang et al. (2011), widespread information technology (IT) use may cause e-waste-related environmental catastrophes. About 500 million PCs died between 1994 and 2003. Five hundred million personal computers contain about 2,872,000 tonnes of plastics, 718,000 tonnes of lead, 1,363 tonnes of cadmium, and 287 tonnes of mercury, posing serious environmental and public health risks if not disposed of properly. Around 60 million tonnes (Mt) of e-waste are produced globally, with some ending up in landfills, creating a significant risk of hazardous chemical leakage. Televisions, computers, cell phones, printers, scanners, and faxes weighed 2.37 Mt in 2009, according to the EPA. Recycling was applied to just 25% of these gadgets, with the rest going to landfills.

Regel-Rosocka (2018) reported that The European Union created 9 Mt of e-waste in 2005 and may produce 12 Mt by 2020. In 2016, the United Nations anticipated 44.7 Mt of e-waste, rising to 52.2 Mt by 2021 (Ananno et al., 2021). Poor direction and management cause incorrect behaviours, public health risks, and environmental hazards, especially in countries without processing facilities. Nishant et al. (2017) indicated that e-waste is projected to become increasingly problematic, with an annual growth rate of approximately 4%, making it the fastest-growing waste stream. Annually, around 40 million metric tonnes of electronic waste are generated. In 2014, e-waste generation totalled 41.8 Mt, predominantly from Asia, North America, and Europe (Dias et al., 2018). The total volume of e-waste was projected to attain 50 Mt by 2018, with an annual increase of 3% to 5% (Cucchiella et al., 2015). Europe exhibited the highest per capita waste generation, followed by Oceania (Dias et al., 2018). E-waste constitutes 1-3% of the total global municipal waste annually (1,636 Mt); in developed nations, this proportion is roughly 5%. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), global annual e-waste generation is increasing at 5-10% per year, whereas the recovery rate remains approximately 10% (Ananno et al., 2021).

While developed nations generate a greater volume of e-waste annually than developing nations, the adverse effects of e-waste are more complex in the latter context. The cost of e-waste recycling in developed countries is significantly higher, ten times that of developing countries. The export of e-waste from developed to developing countries is a significant debate and controversy, with developed nations asserting that the rationale is business, a highly inequitable stance. Furthermore, due to the insufficient experience and equipment for e-waste disposal in developing countries, authorities often resort to incineration or landfill dumping, exacerbating the issue. IT manufacturers are responding to pressures from various stakeholders to create environmentally friendly products by utilising raw materials that are not harmful to the environment (Echegaray & Hansstein, 2017). In terms of e-waste disposal, several countries have achieved notable advancements in this area; however, in several Middle Eastern countries, the implementation is still limited.

Despite the significance of e-waste, many individuals prioritise other issues as more pressing. Consequently, society continues to confront a significant challenge posed by e-waste, prompting governments to implement strategies to address the issue. When a computer malfunctions, the owner typically either disposes of the device or retains it at home; both scenarios pose risks to public health. Public organisations face pressure from customers, competitors, regulators, and society to adopt green information technology (GIT) practices (Coffey et al., 2013). Public organisations have increased their investments in IT in recent years, which serves as the primary source of e-waste. The increasing e-waste generated by such organisations has rapidly reached alarming levels; however, organisational managers have historically overlooked its detrimental environmental effects. The Thi-Qar province in Iraq lacks e-waste statistics; however, numerous computers, photocopiers, printers, and unused faxes are abandoned on shelves and streets. In Thi-Qar, most e-waste management operations are conducted by garbage collectors, encompassing collection, segregation, dismantling, and disposal activities. Many methods employed for e-waste treatment pose risks without the appropriate technologies and equipment. Additionally, inadequate waste disposal practices employed by various Thi-Qar municipalities typically involve the open burning of plastic waste, exposure to hazardous solvents, the dumping of acids, and extensive general dumping.

Therefore, a survey questionnaire was created to examine the institutional pressures influencing public organisation managers’ behaviours concerning adopting environmentally sustainable e-waste disposal practices. The research included 302 organisations from diverse sectors: higher education, construction, banking, health services, manufacturing, oil and gas, agriculture, education, information and communication, insurance, water supply, sewerage management, and transportation. Emails were dispatched to the managers of the targeted organisations, containing requests for participation and accompanying instructions. Participants were selected based on prior research demonstrating that managers recognize the motivations for adopting these practices (Krell et al., 2016). Akman and Mishra (2015) observed that diverse socio-demographic characteristics among societal groups can result in differing behavioural patterns.

3. RESEARCH MODEL AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Institutional theory explains how social and cultural pressures impact organizations, leading them to adopt similar practices. It identifies three types of pressures: coercive, which arise from dependencies on other organizations; normative, which stem from professional standards; and mimetic, which occur in uncertain situations where firms imitate successful peers. These pressures result in a shared set of values and practices among organizations in the same field, ultimately influencing managerial decisions and creating a uniform organizational landscape.

Institutional pressures significantly influence the adoption of e-waste management systems, as evidenced in the literature. This discussion primarily focuses on external pressures that drive firms to adopt voluntary environmental strategies, exceeding the performance levels mandated by environmental legislation (Daddi et al., 2016). Developed an institutional theory to explain how firms in Iraq adopt environmentally responsible e-waste disposal practices. The research posited that coercive forces have predominantly influenced environmental management practices, leading firms across various industries to adopt comparable approaches. Consequently, public organisations faced growing pressure from customers and shareholders, leading to proposed legislative changes to enhance their environmental performance. Scholars, journalists, academics, and governments have studied e-waste’s environmental impact. Executives influence e-waste disposal rates, promoting pro-environmental behaviour as companies seek for sustainability. Implementing ecologically acceptable electronic waste disposal depends on practical, theoretical, and legal considerations (Chen et al., 2011).

To mitigate the negative consequences of IT, academics have established the concept of coordination to address these concerns throughout the e-waste lifecycle. Environmental disposal of e-waste has become a hot concern. Most explanations for ecologically responsible e-waste disposal use the institutional approach. This method stresses how companies gain legitimacy by following societal norms and industry practises (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). During institutionalisation, organisations incorporate e-waste disposal values and practises, resulting in a convergence of practises and reactions (Oliver, 1991).

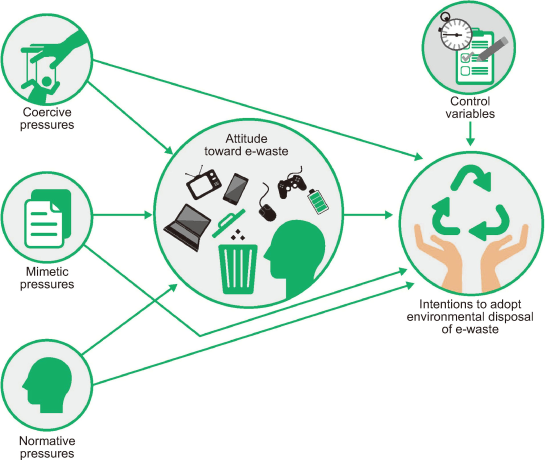

This study developed a research model that emphasises coercive pressure, normative influence, and imitation as institutional constraints affecting e-waste environmental disposal, following an examination of the institutional perspective. The research demonstrates how external pressures compel organisations to manage e-waste in an environmentally responsible manner. From an institutional perspective, the pressures identified as independent variables in the research model influence the rapid organisational attitude that impacts behavioural outcomes (Krell et al., 2016). A research model has been developed to elucidate the key variables influencing the adoption of environmental disposal practices for e-waste, grounded in a thorough literature review. The study assessed three institutional forces to demonstrate a comprehensive approach. The model demonstrates that institutional pressures serve as independent variables influencing managers’ intentions regarding e-waste disposal. Attitudes served as mediators in independent-dependent relationships. Fig. 1 illustrates the research model and its associated constructs. The subsequent section examines the three pressures.

3.1. Coercive Pressures

Numerous government agencies impact the e-waste disposal practices of public organisations. Legislation enables authorities to establish and implement coercive restrictions. Numerous studies have indicated that enacted laws and regulations impact companies (Alziady, 2018; Alziady & Enayah, 2019). Public organisations impose penalties on e-waste disposal enterprises for noncompliance, either directly or indirectly. Institutional theory posits that coercive pressures originate from institutions establishing explicit norms that corporations must adhere to. The concept posits that institutions must possess sufficient strength to administer rewards or penalties for disobedience (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Coercive pressures influence environmental management practices, leading to similar procedures across industries, as noted by Jennings and Zandbergen (1995).

Institutions allocate resources to manage the disposal of e-waste. Furthermore, federal and municipal authorities require public organisations to manage e-waste disposal, thereby limiting the actions of companies. According to DiMaggio and Powell (1983), resource dependency is a driving factor behind coercive forces. Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) contended that influential actors controlling limited resources may require dependent organisations to implement structures that align with their interests. The survival of resource-dependent groups often necessitates adherence to specific protocols. Political influence and the requirements for legitimacy exert pressure. Recent federal and local government regulations mandate that public organisations adhere to environmental protection standards. Addressing requests is advantageous for businesses and mitigates the risk of penalties.

Resource-dominant organisations, government agencies, and other entities may compel corporations to implement effective e-waste disposal policies if they perceive that the activities of public organisations are detrimental to society. Research indicates that regulations are essential for fostering environmental practices (Daddi et al., 2016; Delmas & Toffel, 2004; Lin & Ho, 2016). Research indicates that coercive pressures are essential for adopting GIT (Daddi et al., 2016; Vejvar et al., 2018). The following hypotheses are presented:

H1: Coercive pressures are positively related to the manager’s attitude towards the environmental disposal of e-waste.

H2: Coercive pressures are positively related to the manager’s intentions to adopt the environmental disposal of e-waste.

3.2. Mimetic Pressures

The success of other adopters or the popularity of a practice incentivises public bodies to adopt it. Public organisations reflect behaviours similar to those of comparable companies. Delmas and Toffel (2004) asserted that networked organisations replicate the behaviours of other firms. Mimetic isomorphism refers to the tendency of companies to emulate industry leaders who benefit from being first movers. The description addresses the environmental disposal of e-waste. An organisation may engage in mimetic pressure by observing that other companies have successfully disposed of e-waste while generating profits. Some companies adopt a prevalent practice without due consideration, leading to its devaluation (Cappellaro, 2014). Mimetic pressure arises from uncertainty regarding the appropriate methods to address a problem, perform a task, or attain an objective (Krell et al., 2016). Organisations may mimic others in response to these pressures during periods of uncertainty. Organisations are believed to emulate successful structurally similar entities (Coffey et al., 2013). Institutions participate in the institutional trend to avoid appearing unique compared to other organisations (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), while still pursuing social legitimacy. Krell et al. (2016) also suggested that organisations may seek solutions from other entities facing similar challenges in the absence of information to address difficulties. Chen et al. (2011) and Coffey et al. (2013) demonstrate significant mimetic pressures. We propose the following hypotheses:

H3: Mimetic pressures are positively related to the manager’s attitude towards the environmental disposal of e-waste.

H4: Mimetic pressures are positively related to the manager’s intentions to adopt the environmental disposal of e-waste.

3.3. Normative Pressures

Professionalisation represents an organisational response to normative pressures (Deng & Ji, 2015). Global decision-makers are addressing the adverse implications of IT and seeking to mitigate these effects. Normative pressures arising from supplier-customer interactions facilitate the identification of innovations, advantages, and expenses. The rise in professionalisation, driven by concerns regarding education and training, generates normative pressures (Vejvar et al., 2018). Companies will engage in environmentally responsible disposal of e-waste when such practices become standard due to normative pressures arising from ongoing interactions with suppliers, consumers, or trade organisations (Deng & Ji, 2015). Normative pressures within institutions originate from professional or industry associations (Krell et al., 2016). In contrast to coercive pressures, normative signals have increased; however, organisations that implement them lack the ability to directly enforce compliance or impose penalties for disobedience (Chen et al., 2011). Decision-makers align with industrial and professional institutions, leading enterprises to adhere to regulations voluntarily. Consequently, decision-makers believe that adherence to professional and industry standards will benefit the organisation. Public organizations are likely to manage e-waste responsibly when decision-makers perceive it as enhancing consumer appeal and showcasing their commitment to environmental sustainability. According to Kuo and Dick (2010), normative forces significantly influence the adoption of GIT practices. The discussion proposes the subsequent hypotheses:

H5: Normative pressures are positively related to the manager’s attitude towards the environmental disposal of e-waste.

H6: Normative pressures are positively related to the manager’s intentions towards adopting environmental disposal of e-waste.

3.4. Attitude Towards Adopting Environmental Disposal of E-Waste

Numerous scholars and researchers assert that attitudes towards the environmental disposal of e-waste are crucial for acceptability and have incorporated these perspectives into corporate operations. The study of attitude, which influences individuals’ perceptions, emotions, and behaviours regarding e-waste, has received significant attention. The proliferation of new technologies in the twenty-first century necessitates disposing of electronic waste responsibly. Simultaneously, the perspectives of public organisation managers regarding e-waste disposal should be taken into account during implementing practices aimed at environmental protection. Allport (1935) defined attitude as “a mental and neurological state of readiness that influences the individual’s behaviour towards all related objects and situations.” The individual’s attitude towards the activity influences their preference for it (Ajzen et al., 2018). Schwartz (1992) characterised attitude as a system of ideas regarding an object or action that may result in its realisation. The attitude towards conduct reflects an individual’s perception of the behaviour in question (Wang et al., 2016). This research analyses managerial perspectives regarding the detrimental effects of electronic waste and its environmental disposal practices.

The extent to which individuals perceive themselves as integral to the natural environment influences their environmental perspectives. Managers will view a behaviour positively if they perceive it yields beneficial outcomes. The conduct will yield adverse effects. The behaviour aligns with the disposition. An initial assessment of attitudes can forecast behavioural performance and elucidate the reasons behind specific behaviours (Ajzen, 1985). This study characterises attitude as the preferences and aversions of organisational managers, noting that environmental attitudes generally affect decisions regarding e-waste disposal. Consequently, the analysis indicates:

H7: A manager’s attitude towards the environmental disposal of e-waste is positively related to the intentions towards adopting the environmental disposal of e-waste.

H8: A manager’s attitude towards the environmental disposal of e-waste mediates the relationship between institutional pressures and intentions towards adopting the environmental disposal of e-waste.

3.5. Relationship Between Institutional Pressures and Intentions to Adopt Environmental Disposal of E-Waste

Improving e-waste collection, treatment, and recycling at the end of a device’s life could enhance resource efficiency and support the circular economy in Iraq. Presumably, adopting environmental disposal of e-waste practices is a realistic approach for organisations to manage current environmental problems from accumulated e-waste. Significantly, companies can acquire a competitive advantage by distinguishing themselves from other organisations by adopting the practice while improving their organisational image and economic performance. Furthermore, adopting the environmental disposal of e-waste practice is an example of institutions’ organisational behaviour request, as the motive to adopt is acceptance instead of maximising organisational efficiency.

Environmental disposal of e-waste is currently a developing field that lacks theoretical and empirical research in Iraq. Public organisations are under increasing institutional pressures to reduce the negative impact of IT on the environment; hence, adopting the environmental disposal of e-waste is vital. Moreover, more managers are experimenting with adopting the environmental disposal of e-waste practice; thus, studies should investigate the intentions towards adopting the practice as key factors. The intention towards adopting the environmental disposal of e-waste practices has additional motivational factors beyond standard IT adoption (Molla et al., 2014). Therefore, the motivational factors include economic benefits, regulatory requirements, stakeholder obligations, and ethical reasons that must be considered when exploring and analysing factors that influence the adoption of environmental disposal of e-waste practices (Thomson & van Belle, 2015).

Although research on the environmental disposal of e-waste has recently increased within the IT discipline, there is still considerable overlap among the influencing factors, making them difficult to distinguish. Nevertheless, managers may choose to adopt environmentally responsible e-waste disposal practices either in response to external pressures or to gain strategic benefits—an understandable decision given the complexity and ambiguity surrounding the issue. Based on earlier studies, this study conceptualised the intention to adopt the environmental disposal of e-waste practices as the dependent variable. The economic performance of public organizations is understandable. Recently, managers of these organizations have started to realise that ignoring their environmental performance is absurd. Diffusion and penetration of e-waste practices in organisations reduces power consumption and carbon emissions, improves operating system performance, and increases interaction and collaboration (Deng & Ji, 2015). Hence, the emerging role of e-waste management and benefits highlight the importance of understanding that continuously practicing environmental disposal of e-waste practices could develop and enhance GIT practices.

4. METHODS

Public entities that are environmentally detrimental are developing green technologies. The focus here was on leaders within the public sector. E-waste is a recent development, leading managers to be more aware, skilled, and informed in selecting and evaluating environmental disposal methods. The target respondents were executives familiar with the company and responsible for e-waste disposal. Prior studies yielded quantitative assessments. Mat Nawi et al. (2024) and Krell et al. (2016) provided six items related to coercive pressure, five items about mimetic pressure, and four items associated with normative pressure. Wang et al. (2016) posed three enquiries regarding attitudes and intentions.

A cover letter proposed the study and solicited questionnaires from managers. Anonymous data analysis holds potential for advancing scientific research. The study conducted in Thi-Qar province involved 490 managers and yielded 440 responses. The analysis excluded 11 incomplete responses from a total of 313, representing 71% of the dataset. A total of 302 surveys were deemed analysable. Reminder letters and phone calls elevated the net study response to 67.6%, indicating a positive outcome. The accuracy of the survey questionnaire was verified through translations into Arabic and subsequent back-translation into English. Measurements were verified by three experts, and a pilot study assessed Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s alpha was greater than 0.70, signifying reliability.

All research constructs employed a seven-point Likert scale ranging from very little (1) to very much (7). Appendix 1 presents the construct and measurement items of the most commonly utilised and effective survey-type research scaling instruments. The research incorporated data from public organisations in Thi-Qar, which are notable contributors to e-waste generation. More than 80% of the 302 respondents, comprising 60 women and 242 men, held college degrees. Employees in higher education, health services, construction, oil and gas, manufacturing, water and sewage, banking, agriculture, information and communication technology, insurance, and transportation sectors have responded. Descriptions of responders are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Descriptive information of respondents

| Category | Label | Proportion (%) | No. of respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Woman | 19.90 | 60 |

| Man | 80.10 | 242 | |

| Education level | Bachelor’s degree | 79.9 | 240 |

| Master’s degree | 20.1 | 59 | |

| Sector representation | Higher education | 26.00 | 79 |

| Education | 17.00 | 51 | |

| Health services | 13.00 | 39 | |

| Building & construction | 10.00 | 30 | |

| Oil & gas | 8.00 | 24 | |

| Manufacturing | 6.00 | 18 | |

| Water & sewage | 6.00 | 18 | |

| Banking | 5.00 | 15 | |

| Agriculture | 4.00 | 12 | |

| Information & communication | 3.00 | 9 | |

| Insurance activities | 1.00 | 3 | |

| Transportation | 1.00 | 3 |

The partial least squares (PLS) is advantageous for investigation due to its robust predictive capabilities and minimal requirements regarding sample size and residual distribution (Chin, 1998). Hair et al. (2010) demonstrated that Smart PLS exhibits greater efficiency. The PLS also assessed the hypothesised correlations among the research variables. PLS is a second-generation multivariate technique that evaluates the psychometric properties of scales designed to measure a variable and estimates the parameters of structural models, including the strength and direction of correlations among model variables (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The study employed a two-step approach to model testing, as outlined by Ananno et al. (2021). The study initially evaluated the measurement qualities of reflective latent concepts through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The study employed structural equation modelling to test the hypotheses.

5. RESULTS

The study operationalised all components using existing metrics based on literature studies. Mat Nawi et al. (2024) and Liang et al. (2007) developed six-item coercive pressures, five-item mimetic pressures, and four-item normative pressures. Wang et al. (2016) assessed attitudes toward e-waste disposal methods using a three-item construct, while also measuring the dependent variable and institutional pressures influencing the adoption of e-waste practices, with all scale items rephrased in English. For Arabic responses, back-translation confirmed the translation. The study identified the measurement model to ensure the survey instrument’s validity and robustness per MacKenzie et al. (2011). Assessing the scale’s psychometric characteristics, convergent, discriminant, and nomological validity required data. Experts proposed questions for each construct to assess content validity. Seven academics from Thi-Qar University and the University of Sumeru examined the survey’s suitability, while IT managers analysed question understandability. Feedback validated the instrument’s suitability and clarity.

5.1. Measurement

We assessed the measuring scale’s reliability, discriminant validity, and convergent validity. Examining item loadings on latent variables examined reflecting item and construct validity and reliability (Hulland, 1999). Using principal component analysis and the maximum likelihood approach, CFA assessed scale reliability and validity. In regions with strong a priori theory, Bagozzi et al. (1991) preferred CFA over exploratory factor analysis. This study tested ideas with pre-validated scales. Higher loadings indicate larger construct-item variation than mistakes in PLS-based CFA (Hulland, 1999).

The study identified five factors explaining 77% of the total variance, with eight values greater than 1.0. Each construct was confirmed to be unidimensional and distinct, with items loading significantly on their respective factors. The analysis followed established guidelines for reliability and validity, utilizing composite reliability instead of Cronbach’s alpha for better accuracy. All constructs showed high reliability, with loading values exceeding 0.70 and average variance extracted values above 0.50, ensuring strong discriminant validity. This rigorous assessment confirms the effectiveness of the measurement scales used in the study (Table 2).

Table 2

Factor analysis matrix

| Items | Mimetic | Coercive | Normative | Attitude | Intention | Communalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI1 | 0.79 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.78 |

| MI2 | 0.80 | 0.09 | 0.115 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.77 |

| MI3 | 0.78 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.75 |

| MI4 | 0.81 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.80 |

| MI5 | 0.86 | 0.1i | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.70 |

| CI1 | 0.15 | 0.81 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.75 |

| CI2 | 0.16 | 0.84 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.74 |

| CI3 | 0.08 | 0.83 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.75 |

| CI4 | 0.12 | 0.83 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.71 |

| CI5 | 0.10 | 0.84 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.74 |

| C16 | 0.12 | 0.79 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.76 |

| NI1 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.76 |

| NI2 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.84 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.77 |

| NI3 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.81 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.80 |

| NI4 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.81 |

| AT1 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.83 | 0.16 | 0.79 |

| AT2 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.82 | 0.11 | 0.84 |

| AT3 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.90 | 0.09 | 0.78 |

| IN1 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.89 | 0.84 |

| IN2 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.91 | 0.81 |

| IN3 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.90 | 0.80 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.43 | 4.08 | 3.19 | 2.30 | 2.22 | 16.22 |

| Explained variance (%) | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.77 |

The text details the validation of a measurement model, confirming its discriminant and convergent validity. It highlights significant factor loadings and t-statistics, indicating that the measures meet the necessary criteria. The analysis also addressed common method bias, using the Harman one-factor test, which revealed no dominant factor and suggested that common method bias was not an issue. Moreover, the intercorrelation matrix showed that factors were not highly correlated, supporting the findings. Overall, the results demonstrate that the constructs are distinct and adequately measured (Table 3).

Table 3

Assessment of reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity of research constructs

| Construct | Coercive | Mimetic | Normative | Attitude | Intention | CA | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coercive | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.78 | ||||

| Mimetic | 0.37 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.80 | |||

| Normative | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.76 | ||

| Attitude | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.75 | |

| Intention | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.79 |

5.2. Structural Model

A path analysis was conducted using ordinary least squares hierarchical multiple regressions to test the proposed hypotheses. This method evaluates how explanatory variables influence outcomes by assessing individual paths. The analysis confirmed good internal consistency with reliability scores between 0.75 and 0.8. An intercorrelation matrix showed no multicollinearity issues, as correlations remained below 0.50 and variance inflation factor values were under 3.3. Additionally, a PLS-structural equation modeling analysis was performed using SmartPLS 3.0 (Ringle et al., 2015) to visualize the structural model, which illustrated the explained variance of the endogenous variables and standardized path coefficients. A bootstrap analysis with 500 resamples was also conducted to determine the significance of the estimates.

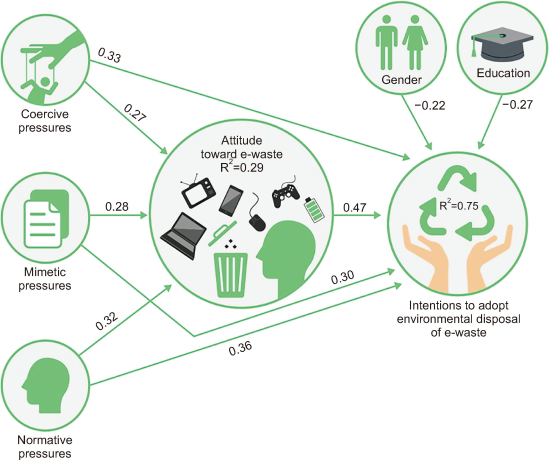

Fig. 2 illustrates that institutional forces (coercive, normative, and mimetic) positively affect managers’ attitudes towards e-waste environmental disposal. The results also demonstrated that coercive, normative, and imitation pressures affected e-waste environmental disposal intentions. The path coefficient from attitude to intention to dispose of e-waste environmentally was substantial, supporting all predictions (H1) suggested that coercive forces strengthen e-waste environmental disposal attitudes. The predicted hypothesis (H1) was supported (β=0.27, T=2.31, p<0.05). The path from mimetic pressures to e-waste disposal attitude (β=0.28, T=2.16, p<0.05) supported (H3). The study found that normative pressures favourably impact attitudes towards e-waste disposal (H5) (β=0.31, T=2.41, p<0.05) and (H2) (β=0.32, T=2.39, p<0.05) (H7) said attitude favourably affects e-waste environmental disposal intentions. The hypothesis was well-supported (β=0.47, T=3.11, p<0.05).

As mentioned in (H4), mimetic pressures increase e-waste environmental disposal intentions. Results supported the hypothesis (β=0.30, T=2.11, p<0.05) (H6) concluded that normative pressure favourably influences e-waste environmental disposal intentions. Results supported the hypothesis (β=0.26, T=2.42, p<0.05). The numbers in Table 4 confirm the path model in Fig. 2. Table 2 presents the factor loadings and communalities for all measurement items, confirming the validity and reliability of the constructs. Table 3 summarizes the results of reliability analysis, convergent validity, and discriminant validity for all research constructs. Attitude towards environmental disposal of e-waste mediates or supplements institutional pressures and the intention to do so, since the indirect and direct effects exhibited comparable signs, confirming H8. Comparing the calculated correlations (i.e., total effects) with the real correlations between the independent variables and the dependent variables confirmed the model’s “goodness of fit.” The study required that the absolute difference between replicated (total effects) and original correlations not exceed 0.10. Fig. 2 shows structural model route coefficients and explained variances. Fig. 2 shows the structural model PLS findings, including standardised path coefficients, significance, and variance explained (R2). Control factors, such as sector, age, and firm, did not significantly affect intention (p-value>0.05), while gender and education did (p-value<0.05).

Table 4

Path model statistics

| Path coefficients | Direct effect | T | Signature p<0.05 | Indirect effect | T | Signature p<0.05 | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI----IN | 0.33 | 2.39 | Yes | 0.12 | 2.03 | Yes | Partial |

| MI----IN | 0.30 | 2.11 | Yes | 0.14 | 2.11 | Yes | Partial |

| NI----IN | 0.36 | 2.43 | Yes | 0.15 | 2.99 | Yes | Partial |

| Gender-----IN | -0.22 | 3.02 | Yes | ||||

| Size--------IN | 0.08 | 1.23 | No | ||||

| Education---IN | 0.27 | 3.02 | Yes | ||||

| Sector-----IN | 0.06 | 1.34 | N0 | ||||

| Age-------IN | 0.09 | 0.98 | No |

6. DISCUSSION

Public corporations are pressured by rivals, consumers, regulators, and community organisations to adopt more environmentally friendly practices that benefit internal and external stakeholders. E-waste disposal must be considered in organisational strategy. Most Iraqi organisations now dispose of e-waste environmentally. Firms must embrace the practice to fit in and function well. Thus, this study seeks to empirically evaluate institutional pressures on e-waste environmental disposal willingness and attitude as a mediator. The study asks: (1) Do institutional forces (coercive, mimetic, and normative) impact public organisation managers’ e-waste practices? (2) How does attitude mediate the relationships among variables? The current work developed and tested a theoretical model to address the problems.

The following section details this study’s primary discoveries, theoretical contributions, and practical consequences. The results showed that the three forces favourably affected respondents’ e-waste environmental disposal. Several interviewees said their companies had had recent successes and a local reputation for e-waste environmental disposal. However, government, supplier, and consumer pressures pressure corporations to prioritise the issue. Coercive pressures have a positive impact on e-waste disposal. Based on the high study sample agreement on pertinent topics, rules are a greater source of coercive pressures than suppliers and customers. Governments were also important in businesses’ choice to dispose of e-waste environmentally. Governments may show their support by boosting the image of e-waste disposal companies. Governments can also reduce information and search costs by providing technical assistance to potential adopters, demonstrating their effectiveness in promoting green behaviours across organisations, especially when they have an organisation-wide impact (Chen et al., 2011). The results verified Molla et al. (2014), who said that government policies that promote GIT practices across the IT life cycle were a significant factor. Chen et al. (2011) found that rules affected pollution control and sustainable development more than mimetic pressure. According to the study, governments in developing countries need to establish clear environmental guidelines for the adoption and disposal of e-waste, as electronic and electrical waste are among the fastest-growing waste categories globally. Therefore, governments worldwide have created legislation to handle device post-consumption (Favot & Grassetti, 2017). In this study, the results are due to the federal government and local administrators’ efforts to impose regulations to control public organisations’ environmental activities and diffuse pro-environmental practices, especially since most public organisation managers try to balance economic and environmental goals, which should be balanced but are often forgotten by companies. Thus, external forces shape e-waste disposal attitudes.

Although Chen et al. (2011) excluded normative pressure, this study found that normative pressures influence attitudes towards e-waste environmental disposal. This suggests that company decision-makers have realised the benefits of adopting the practice. Equally, corporations aim to build links with other firms, and professional groups have used GIT to profit. Due to the ubiquity and maturity of e-waste procedures, the two studies found different results. Most responders want to recycle electronics, justifying their e-waste disposal habits. Mimetic stresses also improve e-waste environmental disposal. Krell et al. (2016) found that copying similar institutions enhances a firm's learning experience. Likewise, it was revealed that decision-makers often prefer adopting other companies’ IT strategies instead of depending solely on internal decisions. A decision-maker could ignore internal technology evaluation conclusions to mimic another company’s selections. In addition, rivals used e-waste environmental disposal to gain significant benefits and satisfy suppliers and consumers. The results match those of Molla et al. (2014), who revealed that select enterprises used GIT investment as a competitive advantage that others copied. The number of other businesses adopting GIT practices was unlikely to affect enterprises. However, if they saw favourable results in other organisations, they were inclined to embrace them (Wang et al., 2016). Since all this is still new, most public organisations are refining their operating methods. However, numerous companies have realised that environmental disposal of e-waste allows a significant change in IT capabilities to increase operational performance and address environmental challenges. Imitating successful businesses is widespread.

Additionally, corporations understood that e-waste management is vital to market share. According to an extensive study, businesses’ effective and efficient e-waste disposal depends on external market dynamics. Thus, institutional forces influence e-waste environmental disposal. This solved the study’s initial equations. Research suggests that e-waste environmental disposal should boost performance and market competitiveness rather than merely complying with environmental protection standards. Thus, environmental e-waste disposal becomes a strategic alternative subject to institutional pressures (Sharma et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2016). The study found three institutional elements affecting GIT: coercive pressure, normative influence, and imitation. The variables also impact e-waste environmental disposal intentions. In contrast, coercive constraints greatly influenced attitude, with imitation and normative pressures impacting managers’ intention to dispose of e-waste environmentally. Since other companies in the sector view e-waste disposal as a legitimate business strategy to win market share, tolerating the conduct has become a daily habit. The company will be more open to IT innovations that cut costs or boost income, regardless of greenness.

The study found that consumers, suppliers, government, and professional bodies no longer significantly impact small businesses’ e-waste practices. When early adopters achieved positive results from green practices, market pressures became a mimetic incentive (Molla et al., 2014). Attitude towards e-waste environmental disposal also affects adoption. Public organisation changes drastically alter industry structure and modify small businesses’ competitive tactics to gain new advantages. Organisations must practise GIT to combat environmental deterioration. In addition, public organisations that embrace environmental e-waste disposal practices develop an environmental culture and pro-environment attitude after recognizing the issue. Finally, organisation managers’ awareness leads to a belief in its effectiveness and ease of implementation. Thus, manager knowledge enhances the desire to continue e-waste environmental disposal (Mat Nawi et al., 2024). Thus, the findings shed light on institutional influences on e-waste attitude and environmental disposal. The practical contribution is that first, the data can help managers adapt the adoption process, spread, and build trust in e-waste environmental disposal practices in enterprises. Managers adopted and maintained the practices to acquire acceptance and economic rewards. Additional study with a broader sample of managers is needed to confirm the applicability of the findings to other public companies.

This study’s results on attitude’s mediation function between institutional pressures and behavioural intentions advance theory and practice. The findings show that management attitudes are a key psychological mechanism for internalising external institutional influences and promoting environmentally responsible e-waste disposal. The mediation effect has serious ramifications. The findings improve theoretical knowledge of e-waste adoption and continuation intentions. The model explained 75% of e-waste environmental disposal intentions and 29% of attitudes. Interestingly, a considerable fraction of the variance remains unexplained, highlighting the need for more research incorporating unmeasured factors.

7. CONCLUSION

This study investigated the influence of institutional pressures on public sector managers’ intentions to adopt environmentally responsible e-waste disposal practices in Iraq’s Thi-Qar province, with particular attention to the mediating role of managerial attitudes. Through a rigorous empirical examination of 302 public organization managers, our research yields several important theoretical and practical contributions while also identifying valuable avenues for future scholarship. The analysis revealed three key findings that advance our understanding of institutional drivers in environmental management. First, coercive pressures emerged as the most potent predictor of both managerial attitudes (β=0.27, p<0.05) and adoption intentions (β=0.32, p<0.05), underscoring the critical role of regulatory frameworks in developing nation contexts. Second, the study empirically validated attitude as a significant mediator (H8 supported), bridging the gap between external institutional pressures and internal behavioral intentions. Third, while mimetic and normative pressures demonstrated measurable effects, their comparatively weaker influence suggests that isomorphic pressures operate differently in Iraq’s unique institutional environment than in developed economies.

Our work makes three substantive contributions to the literature. Theoretically, we extend institutional theory by demonstrating its applicability to e-waste management in conflict-affected regions, while simultaneously enriching the Theory of Planned Behavior by contextualizing attitude formation within institutional frameworks. Methodologically, we advance measurement approaches for developing contexts through our rigorous translation and validation process, which included expert panels, pilot testing, and CFA. Practically, our findings offer evidence-based guidance for policymakers seeking to improve e-waste management in similar institutional environments.

Several limitations warrant consideration. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, suggesting the need for longitudinal studies to examine how institutional pressures and attitudes evolve. Our focus on public sector organizations in one Iraqi province limits generalizability, inviting future research across sectors and geographical contexts. Additionally, while we examined three institutional pressures, other factors such as organizational culture or resource constraints may moderate these relationships. These limitations notwithstanding, our findings have important implications. For theory, they demonstrate how institutional forces shape pro-environmental behavior in developing economies, challenging assumptions derived primarily from Western contexts. For practice, they suggest that policy interventions should prioritize regulatory enforcement while simultaneously cultivating positive attitudes through training and awareness programs. Future research should explore how digital technologies might amplify institutional effects and how cost-benefit considerations influence adoption decisions. By illuminating the institutional determinants of e-waste management in Iraq, this study provides a foundation for both scholarly advancement and practical improvement in environmental governance. As electronic waste continues to grow as a global challenge, understanding these institutional-behavioral linkages becomes increasingly vital for sustainable development.

REFERENCES

, , (1985) Action control: From cognition to behavior Springer Berlin Heidelberg From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior, pp. 11-39, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2

, , , , , (2018) The handbook of attitudes, volume 1: Basic principles Routledge The influence of attitudes on behavior, pp. 59-367, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315178103

, (2015) Sector diversity in green information technology practices: Technology acceptance model perspective Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 477-486 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.009.

, (1935) Handbook of social psychology Clark University Press Attitudes, pp. 798-844, https://www.scribd.com/document/333120405/Allport-G-W-1935-Attitudes-in-Handbook-of-Social-Psychology-C-Murchison-798-844Article Id (other)

(2018) Studying the effect of institutional pressures on the attitudes of the managers of small enterprises in Thi-Qar province toward intention continuance environmental disposal of e-waste Journal of Economics and Administrative Sciences, 24, 24 https://doi.org/10.33095/jeas.v24i107.1287.

, (2019) Studying the effect of institutional pressures on the intentions to continue green information technology usage Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility, 4, 4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41180-018-0023-1.

, , , , (2021) Survey and analysis of consumers' behaviour for electronic waste management in Bangladesh Journal of Environmental Management, 282, 111943 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.111943.

, , (1991) Assessing construct validity in organizational research Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 421-458 https://doi.org/ .

, (2018) Public understandings of e-waste and its disposal in urban India: From a review towards a conceptual framework Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 1053-1066 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro. .

(2014) Book review: Institutional theory and organizational change Organization Studies, 35, 1893-1896 https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840614534386.

, , , (2011) An institutional perspective on the adoption of green IS & IT Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 17, 5-27 https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v17i1.572.

, (1998) Modern Methods for Business Research Psychology Press The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling, pp. 295-336, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781410604385-10/partial-least-squares-approach-structural-equation-modeling-wynne-chin Article Id (other)

, , (2013) Small business in a small country: Attitudes to "Green" IT Information Systems Frontiers, 15, 761-778 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-013-9410-4.

, , , (2015) Recycling of WEEEs: An economic assessment of present and future e-waste streams Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 51, 263-272 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser. .

, , , (2016) Exploring the link between institutional pressures and environmental management systems effectiveness: An empirical study Journal of Environmental Management, 183, 647-656 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.09.025.

, , , (2004) Stakeholders, the environment and society Edward Elgar Publishing Institutional pressure and environmental management practices, pp. 230-245, https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=22075Article Id (other)

, (2015) Organizational green IT adoption: Concept and evidence Sustainability, 7, 16737-16755 https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/7/12/15843. Article Id (other)

, , , (2018) Waste electric and electronic equipment (WEEE) management: A study on the Brazilian recycling routes Journal of Cleaner Production, 174, 7-16 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.219.

, (1983) The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields American Sociological Review, 48, 147-160 https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101.

, (2017) Assessing the intention-behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: The case of Brazil Journal of Cleaner Production, 142, 180-190 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.064.

, (2017) E-waste collection in Italy: Results from an exploratory analysis Waste Management, 67, 222-231 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.05.026.

, (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39-50 https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312.

(1999) Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies Strategic Management Journal, 20, 195-204 http://www.jstor.org/stable/3094025. Article Id (other)

(2018) An integrated approach to establish e-waste management systems for developing countries Journal of Cleaner Production, 170, 119-130 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.137.

, (1995) Ecologically sustainable organizations: An institutional approach The Academy of Management Review, 20, 1015-1052 https://doi.org/10.2307/258964.

, , (2016) The impact of legitimacy-based motives on IS adoption success: An institutional theory perspective Information & Management, 53, 683-697 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.02.006.

, , (2017) E-waste: An overview on generation, collection, legislation and recycling practices Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 122, 32-42 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.01.018.

, , , (2007) Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management MIS Quarterly, 31, 59-87 https://doi.org/10.2307/25148781.

, (2016) Institutional pressures and environmental performance in the global automotive industry: The mediating role of organizational ambidexterity Long Range Planning, 49, 764-775 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2015.12.010.

, , (2011) Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques MIS Quarterly, 35, 293-334 https://doi.org/10.2307/23044045.

, , , , (2024) Green information technology and green information systems: science mapping of present and future trends Kybernetes, 54, 3136-3155 https://doi.org/10.1108/k-10-2023-2139.

, , (2014) Green IT beliefs and pro-environmental IT practices among IT professionals Information Technology & People, 27, 129-154 https://doi.org/10.1108/itp-10-2012-0109.

, , (2017) Do shareholders value green information technology announcements? Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 18 https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00466.

(1991) Strategic responses to institutional processes The Academy of Management Review, 16, 145-179 https://doi.org/10.2307/258610.

(2018) Electronic wastes Physical Sciences Reviews, 3, 20180020 https://doi.org/10.1515/psr-2018-0020.

, , (2015) SmartPLS 3 https://www.smartpls.com Article Id (other)

, (1992) Advances in experimental social psychology Academic Press Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries, pp. 1-65, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

, , , , (2024) Electronic waste disposal behavioral intention of millennials: A moderating role of electronic word of mouth (eWOM) and perceived usage of online collection portal Journal of Cleaner Production, 447, 141121 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141121.

(2015) Antecedents of green IT adoption in South African higher education institutions Electronic Journal Information Systems Evaluation, 18, 172-186 https://academic-publishing.org/index.php/ejise/article/view/180. Article Id (other)

, , , (2018) Strategic responses to institutional forces pressuring sustainability practice adoption: Case-based evidence from inland port operations Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 61, 274-288 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2017.08.014.

, , (2021) Bioleaching of electronic waste Pollution, 7, 141-152 https://doi.org/10.22059/poll.2020.308119.872.

, , (2016) Determinants of residents' e-waste recycling behaviour intentions: Evidence from China Journal of Cleaner Production, 137, 850-860 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.155.

, , (2011) Designing IT systems according to environmental settings: A strategic analysis framework The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 20, 80-95 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2011.01.001.

, (2016) A review of current progress of recycling technologies for metals from waste electrical and electronic equipment Journal of Cleaner Production, 127, 19-36 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.004.