1. INTRODUCTION

Information is an essential resource for organizational decision-making, enabling companies and institutions to respond swiftly to the demands of a competitive environment (Laudon & Laudon, 2000). However, for this process to be effective, it is necessary not only to access information but also to absorb and transform external knowledge into a strategic advantage. In this regard, absorptive capacity has become one of the main drivers of business competitiveness, allowing organizations to incorporate new knowledge and enhance their innovative capabilities (Spithoven et al., 2010).

Information management (IM) is still not standardized in many firms, despite its increasing significance, which restricts its strategic potential (Choo, 1998). The lack of organized procedures for gathering, analyzing, and using data impedes flexibility and creativity, posing problems for public and private sectors alike. In order to transform knowledge into a competitive advantage and spur innovation, this situation serves as further evidence of the necessity of incorporating IM into organizational dynamics.

The theory of dynamic capabilities provides a theoretical framework for understanding this challenge, highlighting the importance of acquiring, processing, and strategically applying information as essential factors for innovation (Barney, 1991; Helfat & Winter, 2011). Within this perspective, absorptive capacity (AC) refers to an organisation’s ability to recognise the value of new external information, assimilate it, and apply it effectively, as defined by Cohen and Levinthal (1990). Subsequent studies emphasize that this capacity, particularly through research and development (R&D) activities, plays a crucial role in organizational innovation (Fosfuri & Tribó, 2008; Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2020; Lopes & de Carvalho, 2018; Murovec & Prodan, 2009; Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2022; Zahra & George, 2002).

Chesbrough (2006) established the idea of open innovation, which emphasizes the value of teamwork in creating novel concepts and solutions. Open innovation stresses the sharing of resources, technology, and expertise among businesses, increasing potential for digital transformation and the creation of new goods and services, in contrast to the traditional innovation model, which only uses internal efforts. Therefore, the ability to build strategic and interorganizational relationships is just as important to innovation success as internal R&D investments.

To explore the relationship between information, knowledge, and collaborative innovation, this study suggests a conceptual model that combines IM and AC inside the open innovation environment. Despite the extensive discussion of these ideas in the literature, there is still a lack of knowledge regarding the impact of stakeholder roles and interorganizational relationships outside of the conventional emphasis on R&D investments (Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2020; Zobel, 2017). While previous work offers a descriptive study of the challenges associated with managing open innovation in practice, the proposal model seeks to provide prescriptive theoretical direction. By bridging the gap between formal frameworks and the dynamic realities of collaborative innovation, these complementary approaches enhance scholarly knowledge and the real-world implementation of innovation management.

This paper is structured into four sections. Section 1 introduces the topic. Section 2 discusses the theoretical foundations of IM, AC, and open innovation. Section 3 integrates these concepts and presents the conceptual model. Finally, Section 4 provides concluding remarks.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

This section outlines the key theoretical concepts that form the foundation of the model proposed in this article: IM, AC, and open innovation. It provides a comprehensive review of the literature on these three themes, examines their interrelationships, and emphasizes how their integration can enhance an organization’s ability to innovate.

2.1. Information Management

IM is the application of the principles of contemporary management to the tasks of acquisition, processing, dissemination (distribution), and use of information in organization environments. This statement is within the scope of information theory, presenting a model composed of sender, message, and receiver, where the information is in the message, enabling communication. In this regard, it is possible to affirm that IM acts centrally in organizational communication, hence the strategic importance of managing information content aiming at broad access to support decision support systems and generating an environment favoring open innovation. In this context, Claude Shannon’s classic proposition in his 1948 article “Mathematical Theory of Communication” states that a communication system consists of five components, emphasizing that the communication channel should maintain neutrality (Shannon, 1948). This reinforces the importance of promoting impartiality and objectivity in an IM model, ensuring unbiased access to information as the final product.

According to Shannon’s 1948 definition (as cited in Guedes & Júnior, 2014), a communication system includes: (i) a source of information that produces messages; (ii) a transmitter that generates a signal from the messages; (iii) a channel that transmits the signal from the transmitter to the receiver; (iv) a receiver that decodes the signal; and (v) a final recipient, which can be a person (user) or equipment to which the original message is directed. The system proposed by Shannon bears similarities to Coadic and François (2004)’s theory of information, incorporating technical elements related to signal compatibility and emphasizing the preservation of neutrality and objectivity in the reception and destination of the signal, as reflected in the information retrieval process. This is the analogy between a proposal of significant influence in the organization and IM, with the integrity of the basis that allows access to the receiver (user) of information.

IM, a general model for applying methods, tools, and solutions to control information flows, presents the informational (documentary) cycle as a unifying element of the steps and tasks involved in IM. Each stage of the information cycle includes technical measures, from which information is represented and organized to enable searching and retrieving information. This primary purpose makes the use of information in the organizational context feasible.

The information cycle combines two dimensions of processing and organization of information records. The dimension of technical processing is represented in steps that involve the representation of the information content to generate metadata that will be inserted into the system for later retrieval by users. The other dimension is represented by the division of IM tasks, organized into cumulative and subsequent steps of arrangements in a format like a flowchart.

IM, within the framework of a communication system, should consider the mathematical theory of information as an element of improvement of the information cycle. It is possible to consider three central aspects in an open innovation model in IM: I. information storage; II. organization of information; and III. information retrieval.

Storage refers to the process in which information items are allocated in a system to be found when requested by users, from a set of metadata that describe them and are the result of classification systems.

According to de Albuquerque and de Araújo Júnior (2014), the organization of information addresses the techniques applied to analyzing and synthesizing informational objects, to represent them to be identified and retrieved later through their attributes and main characteristics.

Information retrieval is the central step of an information system. It consists of identifying informational items in a system or collection that have been stored and demanded by users with the support of professional mediation, or autonomously in databases or information systems.

According to Cacaly et al. (2008), because specialized mediation is a prerequisite for retrieval operations and the delivery of results to users, it is both feasible and essential to enhance the information retrieval process by diagnosing users’ informational needs. This is true both at the level of the form of response and the extension of the field to be explored. Mediation between applicants and the available documentary and informational resources typically requires a high level of interaction between the user and the information expert.

IM is only effective in organization environments based on the full knowledge of the informational needs of users of information systems. This statement is the assumption of IM and has repercussions in constructing management models. It is possible to detect in the various models that we will present below common characteristics, all revealing a conductive wire in the communication system.

The Open Archival Information System model, in the proposition by Serra Serra (2008), establishes input and output interfaces to the archival IM system. The input interface is referred to in the English acronym SIP as Submission Information Package and is under the responsibility of the document producers. In IM, as part of the technical processing stage, the responsibility interface of the system managers is represented by the AIP (Archival Information Package). The interface is called the Dissemination Information Package (DIP) at system output or information retrieval. In this model, the input, processing, and output steps that characterize the models and IM are well delineated.

IM must be able to support the choice of organization strategy and the management model of information systems. The full knowledge of the informational needs of the users of the systems must support this dual function. This fact can be corroborated by the analysis of the IM models presented, where the dissemination of information is the final and most important result in a communication system, as proposed by Shannon (1948) and Coadic and François (2004).

The three basic tasks of IM, 1. collection; 2. processing; and 3. systemic dissemination of information in the organization, should follow the basic requirement to be considered in IM, which is the adaptation of information transfer models in the organization environment. Thus, the management of user requirements, as proposed by Davenport (2005), must combine the information needs of users and those of supplier channels through knowledge of the requirements of those who need information to consolidate the trust of suppliers and decision-makers.

In a more current context, IM is also being shaped by new technologies (e.g. artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and big data), which enable the processing of large volumes of data and the generation of real-time insights. These tools allow for more agile and efficient IM, expanding the scope of innovation and enhancing organizations’ ability to respond to market changes and uncertainties. According to Laudon and Laudon (2020), integrating these technologies into IM has the potential to revolutionize how organizations capture, analyze, and use information, making them more dynamic and competitive.

The adoption of effective IM practices is essential to optimizing knowledge sharing and transfer—processes that serve as key drivers in strengthening organizational capabilities (Pavão et al., 2023).

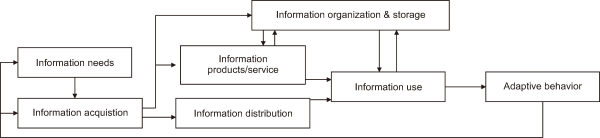

In this study we use the IM process Model proposed by Choo (1998). This model outlines the systematic flow of information within an organization, highlighting how information is transformed into knowledge that supports decision-making and adaptive behavior. The following is an explanation of each stage (Fig. 1 [Choo, 1998] is presented at the end of the article):

1. Identifying Information Needs: The IM process begins with recognizing what information is necessary for the organization. This step involves understanding the internal and external information requirements that are critical for achieving organizational goals.

2. Information Acquisition: Once the information needs are identified, relevant data is gathered from various sources. This can include both internal databases and external environments, ensuring that the organization has access to the information it needs.

3. Information Organization and Storage: The acquired information is then systematically organized and stored. Proper classification, indexing, and archiving of information enable easy retrieval and ensure that the information remains useful over time.

4. Development of Information Products and Services: At this stage, raw information is transformed into meaningful products and services that cater to the organization’s needs. This can include reports, dashboards, analytical tools, or customized information services.

5. Information Dissemination: After processing, information is distributed to relevant stakeholders. This ensures that the right information reaches the right people at the right time, facilitating informed decision-making.

6. Information Use: This stage refers to how information is applied within the organization. It is used to support decision-making, problem-solving, and strategy formulation.

7. Adaptive Behavior: The final stage involves using information to adapt to the environment. This reflects the organization’s ability to learn, innovate, and evolve based on the insights gained from information use.

It is evident that IM is essential to gathering, analyzing, and sharing strategic data that informs choices and helps businesses adjust to ever-changing market conditions. AC—the ability of an organization to recognize, absorb, and use external information to optimize value creation—is intimately related to this process. The main ideas surrounding AC will be covered in the section that follows.

2.2. Absorptive Capacity

AC starts from the epistemological perspective of the theory of resource-based view (RBV), proposed by Wernerfelt (1984) and Barney (1991). RBV handles the firm’s specific resources to develop competitive advantages. The concept is defined by Cohen and Levinthal (1990) as the ability of an organization to recognize the value of new, external information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends, as critical to its innovative capabilities.

According to the model of Cohen and Levinthal (1990), AC depends on two antecedents: the previous level of prior knowledge of the organization, and the direct interface of the organization with its external environment and sources of knowledge. Both are dependent on the effects of the conditions of the appropriability regimes. They allow the organization to develop the AC process, consisting of identifying new information, assimilating the acquired information, and applying the acquired knowledge for commercial purposes capable of promoting innovation and/or innovative performance.

Cohen and Levinthal (1990) also highlight the relevance of the R&D department associated with appropriation capacity. Also, the R&D area generates new knowledge and contributes to developing the organization’s AC. Hence, the model analyzes the empirical importance of AC based on the responsiveness of the R&D activity compared to the existing learning environment (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

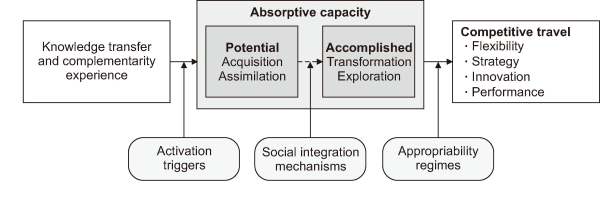

A decade after the initial publication of Cohen and Levinthal (1990) on AC, Zahra and George (2002, p. 186) revisited the theoretical model. They broadened its concept by defining it as “a set of routines and organizational processes by which organizations acquire, assimilate, transform and apply knowledge to produce a dynamic organizational capability.”

Zahra and George (2002) propose the relevance of prior knowledge of the organization, combined with the acquisition of new sources of information from the relationship of organizations with their external environment through organizational processes and routines, to develop new competencies (Zahra & George, 2002).

The multidimensional concept proposed by Zahra and George (2002) points out that AC is divided into two different sets: the potential capacity (PACAP)—which involves the dimensions of acquisition and assimilation of knowledge; and the realized capacity (RACAP), which emphasizes the dimensions of knowledge transformation and application. These two subsets defined by the authors can be useful, since organizations permeate different contexts. An organization may have a greater ability to understand technical problems (acquisition and assimilation), but may not be able to use this knowledge for innovation (transformation and application).

Moreover, Zahra and George (2002) indicate that different levels of interaction are necessary when it comes to knowledge transfer processes, namely: (1) individual, which has the focus of analysis on the organization’s employees; (2) group, which refers to work teams, functional areas and divisions, business divisions, and branches; (3) organizational, which relates to the organization as a whole; and (4) inter-organizational, which refers to different levels of interactions with other partners and stakeholders, which can be through strategic alliances, clusters, industries, joint ventures, and national innovation systems. Here, through Fig. 2 (Zahra & George, 2002) presented at the end, we present the model developed by Zahra and George that will serve as a basis for analysis in this work.

Zahra and George (2002) proposed a model that indicates that previous experience and the need to acquire new knowledge from the external environment are important antecedents for potential AC. From the activation triggers, called events that cause the organization to need adaptation and/or respond to new demands (internal or external), the authors define the need for new information for the maintenance and survival of the organization in the environment where inserted.

Thus, in starting to acquire and assimilate new information acquired in the organizational environment (internal or external), the organization starts to develop mechanisms of social integration (structural, cognitive, and relational), which require knowledge sharing among internal players. This step is necessary so that, after the organization and storage of new information, it can be conceived and internalized by all organization members (Zahra & George, 2002).

Implementing these mechanisms facilitates information flows and reduces the distance between PACAP and RACAP. This improves the assimilation and transformation of information and may explain some performance variations between companies in the same industry. As a result, the exploitation/application of new knowledge drives organizational performance, innovation, and competitive advantage, with differences among organizations arising from the way they utilize resources and develop their organizational capabilities (Zahra & George, 2002).

AC enables organizations to identify, assimilate, and apply information from the external environment, which is essential in open innovation environments where the exchange of information across organizational boundaries is crucial. By effectively managing and integrating external information, organizations can leverage diverse insights, accelerate the innovation process, and reduce the risks associated with internal development. The following section will address the key concepts of open innovation to understand its relationship with IM and AC.

2.3. Open Innovation

Open innovation has consolidated itself as a relevant theme on the agenda of organizations over the last few years. The collaborative character of the model instigates networking initiatives and the improvement of new relationships between partners. Innovation development without considering the external environment to obtain resources, ideas, and technologies, and establish strategic partnerships is indefensible in the current scenario.

Given this context, adaptations were necessary. Large corporations began to learn about new processes and ways of innovating with those who started in a smaller structure—for example, startups who quickly established themselves, creating new markets or even breaking with existing markets.

Regarding open innovation partners, the following can be mentioned: customers, suppliers, research institutions, universities, and associations, among others, and even competitors themselves (Chesbrough, 2006). In the case of the latter they are characterized, above all, by cooperation processes in which, at the beginning of certain projects, there is a collaborative relationship. When the common objective of the partnership is reached, each party involved follows its market strategy, establishing an environment of competition. A common situation in projects in the pharmaceutical area, for example, is where laboratories first partner to study a medicine for a disease. Secondly, when the project results are obtained, each laboratory follows its own marketing strategy. This approach is called coopetition, first a moment of cooperation and then, next, a stage characterized by competition.

It should be noted here that human resources are an important part of the innovation process. Besides people, another resource that is essential for conducting organizational activities is the information element, one of this study’s central subjects.

A recent study by Engelsberger et al. (2023) addresses human resource management in collaboration, underscoring the importance of raising awareness among teams and individuals to succeed in open innovation processes. In the words of Majchrzak et al. (2023, p. 1), “managing human interaction across organizational boundaries is therefore central to open innovation.” Together with people, at the heart of this importance is the role that information and informational resources play in working among teams and partners.

Therefore, concerning the ‘information’ resource in collaborative innovation processes, it is possible to state that information is consolidated as a fundamental input in such processes. From how the partner network handles information, the degree of trust may or may not be accentuated, which is one of the indispensable elements for the success of the collaboration. Thus, the proper sharing of information will dictate the performance of collaborative work. Observations are also punctuated by the study by Wang et al. (2023) on the different conditions of the members of a strategic alliance and the impact of information sharing on expected results, which concludes: “If these problems cannot be resolved, the operation of alliances may fail” (Wang et al., 2023, p. 1).

In a collaboration context, different open innovation practices can be observed from the study by Chesbrough and Brunswicker (2013), these being monetary and non-monetary. Next are some innovation practices, separating them by the dimensions of open (inbound and outbound): inbound—dealing with licensing (intellectual property); innovation awards for suppliers; collaboration with external suppliers of R&D services; idea and start-up contests (related to business ideas); specialist services from open innovation intermediaries (e.g. Ninesigma, InnoCentive); university fellowships; co-creation with customers and consumers; crowdsourcing to solve innovation problems; informal networks (e.g. fairs, networked institutions); R&D consortia supported by public funding.

The flow of partnership in inbound practices reveals a strategy to obtain resources, ideas, and technologies from the external environment to the organization. When observing the intellectual property strategy, companies can obtain licensing from the payment of royalties to inventors for use in part of developing a new product/service, and with the possibility of establishing partnerships beyond licensing if it is of mutual interest.

Identifying key partners can be enhanced by participating in established network associations and organizations in informal networks such as fairs and events. Promoting competition of ideas (some examples are hackathons and crowdsourcing) in addition to capturing new ideas and solutions to known problems can also be a more proactive way to identify partners. In these terms, co-creation rounds bring good insights to organizations from the customer/user experience that can contribute to improvements or even the proposal of new products/services, for example, through prototyping processes.

Some companies have used partnerships with universities through R&D contracts with or without the support of public funds to conduct the initial stage of their projects—basic research.

As for open innovation practices, outbound, some examples are listed: selling patents and intellectual property licences; incubating businesses and venture capital for businesses (e.g. incubation programs for new start-ups); spin-offs; selling market-ready products; participating in standardisation programs (e.g. in Brazil: International Organization for Standardization, Brazilian Technical Standards Association); joint venture activities with external partners; donations to for-profit or non-profit organizations.

In the definition of dimensions of open innovation practices, inbound (from outside to inside) and outbound (from inside to outside) flows can be classified. The use of ideas and technologies obtained in the external environment characterizes the inbound flow from the point of view of the organization that absorbs these external resources. In turn, when the organization makes ideas, technologies, etc., available to the external environment, the outbound flow is what describes the opening dimension.

According to Chesbrough and Crowther (2006), inbound open innovation means generating ideas and results in R&D from information from suppliers, customers, and other external players (acquisition or joint development of technologies), which can enhance the innovation capacity of organizations. On the other hand, outbound open innovation is characterized by the delivery of new technologies by the organization through the commercialization of new products or services for specific organizations.

Vanhaverbeke and Gilsing (2024) reinforce that the motivation for inside-out and outside-in practices is strategically perceived to develop new products. Still, some practices can be adopted for financial benefits, such as the availability of unused technologies and ideas and the commercialization of intellectual property. Therefore, the authors focus on open innovation inbound activities and the AC that needs to be built to successfully engage in these activities (Spithoven et al., 2010). In the words of Aliasghar and Haar (2023, p. 1), “in order to engage simultaneously in both ‘buying’ and ‘selling’ activities, organizations need to develop specific capabilities to manage knowledge inflows and outflows, e.g., absorptive and desorptive capacities.”

El Maalouf and Bahemia (2023, p. 2) study the results obtained in open innovation practices in the inbound dimension and find that “there are ‘learning’ benefits from openness to the knowledge of external partners as organizations create routines of processing information to find and choose appropriate partners.”

The study by Spithoven et al. (2010, p. 10) assumes the recognition of the approximation between open innovation and AC: “The discussion on open innovation suggests that the ability to absorb external knowledge has become a major driver for competition. For R&D intensive large organizations, the concept of open innovation in relation to AC is relatively well understood.” Spithoven et al. (2010) point out that, in the process of inbound open innovation, organizations use the external environment to seek knowledge and technology, not depending only on internal R&D. For this, they must develop AC to internalize and use external knowledge.

Based on their findings, Spithoven et al. (2010) state that the main source of information for developing R&D and innovation lies in the previous experience of the organization’s team. However, other important sources of information are universities, events, publications, and specialized journals. Further, Spithoven et al. (2010) still comment that to develop AC, organizations may need the help of external players, such as research centers and universities, to build AC at the inter-organizational level. Finally, their article defines the concept of AC as a precondition for open innovation and points out that organizations without AC use knowledge collectively through external players.

In turn, open innovation expands the available sources of information, strengthening AC and fostering a continuous cycle of learning and innovation. This symbiotic relationship highlights the importance of aligning AC with open innovation strategies to maximize the benefits of external collaboration and knowledge flow. Having concluded the presentation of the concepts that guided the development of this article, the following section will outline the methodological procedures used in the research.

3. METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURES

The methodological approach for this conceptual model study involves a comprehensive review of the existing literature related to open innovation, IM, and AC. Initially, relevant scholarly articles and books were identified and analyzed to understand the theoretical underpinnings and establish a foundational basis for the proposed model. The conceptual framework integrates key elements from two seminal models: the procedural model of information (Choo, 1998) and the AC model (Zahra & George, 2002).

In order to provide a framework that corresponds with the phases of the innovation funnel, the study uses a qualitative technique, emphasizing theoretical synthesis and conceptual integration. The body of research on open innovation, IM, and AC was compiled and interpreted using the narrative review as a methodological technique. Narrative reviews (Baumeister & Leary, 1997) provide a more flexible and interpretative approach than systematic reviews, which adhere to a predetermined protocol for data collection and analysis. This enables researchers to critically engage with a variety of theoretical perspectives and discover conceptual connections between various studies. This approach makes it possible to identify theoretical gaps and create a cohesive conceptual model by facilitating a thorough knowledge of the development of important concepts, combining knowledge from important studies and empirical research.

The process toward a conceptual model proposal involved a systematic synthesis of concepts from different domains to ensure that the resulting framework adequately reflects the complexity of IM and AC within open innovation projects. The primary goal of this methodology is to contribute to theoretical advancements, and provide actionable insights for both academic researchers and practitioners in public and private organizations engaged in innovation initiatives.

4. EMPIRICAL STUDIES OF ABSORPTIVE CAPACITY AND INFORMATION MANAGEMENT AND OPEN INNOVATION

This section discusses the concept of AC and IM as a necessary resource for this process that contributes to developing open innovation in the organizational context. Initially, Cohen and Levinthal (1990) and Zahra and George (2002) have already mentioned the importance of information for innovation. According to Lane et al. (2006) and Camisón and Forés (2010), the dynamism of AC is vital to improve the innovation performance of organizations, as well as enhance competitive advantage. Thus, studies that relate AC and innovation affirm that the use of knowledge external to the organization enables the increase and creation of new skills through the transformation of knowledge and/or its integration with the other resources of the organization (Camisón & Forés, 2010; Cassiman & Veugelers, 2006).

The concept of open innovation is related to the concept of AC when considering external knowledge as an important source for innovation. As organizations manage the internal and external information of their stakeholders, they need to develop an adequate IM infrastructure that allows integrating tools, techniques, and programs that will help the players involved in the process to share, collaborate, and communicate more effectively, making efficient use of information (Davenport & Prusak, 2000).

Tether and Tajar (2008) conducted a study to investigate organizations’ main sources of information for innovation from specific sources of knowledge. Their main findings indicate that the main information can be found in specific companies or informal media sources. The authors point out that there are specialized sources of information in consulting companies, public or private teaching, and research organizations, and that more innovative companies usually consult these sources with a greater propensity for AC, more significant social capital, and relationship capacity.

Organizations that seek this type of knowledge usually use it to promote innovation, combined with previously existing knowledge in the internal organizational environment. The study also found significant differences between the sources of information used by industries compared to service providers, which are more likely to use specialized knowledge. The latter mostly rely on hiring consulting services, rather than utilizing scientific research results and relationships with public universities (Tether & Tajar, 2008).

However, AC does not depend on a formal relationship with an external source of knowledge. This may come from reading an industry journal, trend analysis, and patent documents, among other forms. Most of the time, the innovations created in an organization are not new in the world, but new in the specific context of an organization. Thus, access to external sources such as consultants, experts, or professionals with previous experience in similar innovation projects can help promote the innovation process (Tether & Tajar, 2008). In the context of open innovation, the main source of information is one in which both parties are aware of the purpose of their engagement. Therefore, organizations must establish collaborative relationships with research groups, universities, consultants, and other relevant knowledge sources, working in synergy to develop innovation projects (Tether & Tajar, 2008).

Huang et al. (2015), in an empirical investigation of Chinese organizations, researched the main barriers to open innovation and identified that low AC is one of the factors that most inhibit this process. Spithoven et al. (2010) and Patterson and Ambrosini (2015) also corroborate, with their studies, that lack of AC can be considered a restriction to open innovation.

Naqshbandi (2016) indicates that for the success of the open innovation process, organizations need to have the capacity to absorb knowledge, acquiring, assimilating, transforming, and applying the knowledge acquired externally. Also, Naqshbandi (2016) highlights the importance of the organization’s interaction with different players in its environment, universities, educational institutions, or even government agencies to acquire and positively take advantage of knowledge in open innovation practices.

Limaj and Bernroider (2019) aimed to investigate the relationship between AC and exploratory and exploitative innovation in the context of small and medium-sized enterprises. Their study found that PACAP has a direct impact on RACAP. Therefore, organizations need to build a strategic innovation mechanism that is initially based on the development of higher levels of AC. The authors believe that RACAP is the main way to promote innovation in organizations, contributing to the findings of Zahra and George (2002).

Lopes and de Carvalho (2018), from a literature review on open innovation, identified that organizations need to develop skills and AC to better take advantage of the results obtained through open innovation and generate competitive advantage. The authors suggest that AC is a relevant skill. The organization must invest time and resources to understand how best to acquire, assimilate, transform, and leverage information for business purposes.

Grama-Vigouroux et al. (2020) conducted a qualitative study with small and medium-sized companies to understand the importance of stakeholders’ relationships in the open innovation process. Their findings suggest that using the multidimensional AC model is necessary to understand open innovation better. The open innovation process can be enhanced through AC, as the organization’s relationship with its external environment and stakeholders demands the absorption of knowledge based on the dimensions of the ACAP construct.

The research evidence indicates that the organizations studied have developed initiatives to absorb knowledge from their external stakeholders. In an example firm, “its employees are motivated to capture external information related to market changes, technological advances, and external patents via their participation in various events such as exhibitions and conferences. Customer and supplier feedback is exploited to increase internal innovation” (Grama-Vigouroux et al., 2020, p. 6).

Furthermore, organizations have developed other initiatives and collaborative platforms to co-create and capture external knowledge to generate innovations. The main source of information for organizations is stakeholders: suppliers, universities, designers, and producers from other industries.

Small and medium-sized enterprises are increasingly becoming part of collaborative innovation networks. In this context, acquiring external knowledge from other players with different expertise is possible. Thus, it is possible to absorb this knowledge and increase organizational performance. Benhayoun et al. (2020) developed a study to identify and propose a scale for measuring AC for small and medium-sized enterprises in the context of innovation networks. As their main results, Benhayoun et al. (2020) identified that organizations could develop knowledge AC to co-develop and commercialize innovations with participation in collaborative innovation networks. Their findings show that acting in a collaborative environment promotes the development of AC and enhances open innovation practices. According to Naqshbandi and Jasimuddin (2022), when organizations have links with other external sources of knowledge, they can find and use necessary information along with information internal to the organization, thus promoting the innovation process.

5. CONCEPTUAL MODEL: CONSTRUCTION

Studies that examine the connection between IM and AC in the increasingly common collaborative setting promoted by open innovation practices are lacking from a theoretical standpoint. The findings of Teirlinck and Spithoven (2013), who note that large organizations typically do better in open innovation because of their greater maturity in AC, support this connection. The authors emphasize the significance of AC in fostering external collaboration and enhancing innovation outcomes, by claiming that small firms with greater internal R&D competence are also more inclined to participate in research cooperation and R&D outsourcing.

The work of Arsanti et al. (2024), which emphasizes regulating information flows within open innovation through absorption mechanisms and knowledge-sharing in collaborative contexts, is very different from the conceptual model put forward in this study. Our model takes a top-down approach by providing a structured integration of well-established theoretical frameworks for managing information and AC within innovation projects, whereas their study takes a bottom-up approach, emphasizing emergent and practical processes that naturally arise through dynamic interactions among actors. Specifically, our model highlights systematic processes and the sequential stages of the innovation funnel, providing a formalized perspective to guide innovation management. In contrast, Arsanti et al. (2024) focus on real-world applications, emphasizing how knowledge sharing and absorption unfold through the intermediary roles of actors across organizational boundaries.

The studies by El Maalouf and Bahemia (2023) and other related works reinforce the need for the proposed model by highlighting critical gaps in the literature. Their analysis identifies key support needs for managers regarding learning routines in the implementation of open innovation practices, emphasizing that only a limited number of recent studies have examined how organizations adjust their capabilities to effectively adopt open innovation (Pinarello et al., 2022; Zobel, 2017).

While previous research focuses on essential organizational capabilities—such as top management support, AC, project management, and dedicated open innovation teams—it overlooks the systematization of IM, a crucial step preceding knowledge absorption. This gap underscores the necessity of a structured approach to managing information flows, as effective open innovation relies not only on dynamic capabilities but also on organized processes that facilitate the acquisition, processing, and application of external knowledge.

The suggested approach overcomes these drawbacks by combining absorptive ability and IM into a unified framework. In order to strengthen open innovation processes and an organization’s capacity to adapt to changing circumstances, this organized perspective seeks to assist businesses in methodically managing information flows.

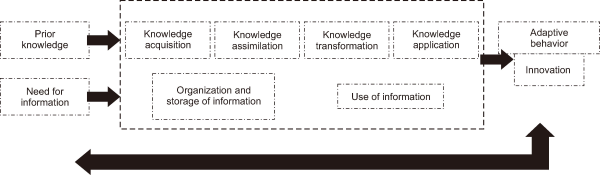

By including key components from Zahra and George (2002)’s AC framework and Choo (1998)’s information process model, this study expands on this realization. By integrating these viewpoints, the model seeks to offer a thorough framework that unites absorptive ability and IM, providing useful advice for businesses looking to improve their open innovation procedures in a methodical manner.

Initially, Fig. 3 presents an approximation of the subjects based on the main concepts presented by the authors mentioned above. Prior knowledge AC and identification of customer/user needs IM is the starting point for systematization by assuming previous experiences impact the current reality, whether these lessons are learned and/or consolidated skills. Similarly, new situations may cause the organization to need adaptation and/or respond to new demands, thus requiring the acquisition of new information.

Therefore, the process of potential AC (acquisition and assimilation) requires the social integration of players and organizational structures (AC), so that new information is organized and stored to make it available to all involved (IM).

For this new information to be used effectively, it is necessary that the organization also develops potential AC (transformation and application). This process of using information is developed through organizational routines, which are developed uniquely by each organization (IM). As a result, the exploitation/application of information transformed into knowledge promotes the organization’s results in terms of performance, innovation, and competitive advantage (AC and IM). Thus, it is evident that organizations’ adaptability and innovation capacity can come from the efficient use of information available in the environment.

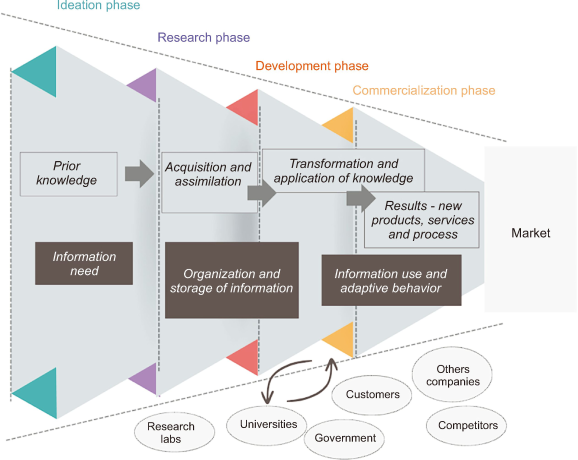

Fig. 4 presents the construction of the theoretical model within the open innovation funnel, with the dashed edges to characterize the permeability with the external environment representing the opening dimensions: inbound, outbound, and coupled.

Stakeholders identified in Fig. 4 represent the potential partners existing in the organization’s external environment in the different stages of the innovation process. In this path, different paths and possibilities may arise until the result of innovation is obtained, such as obtaining and/or licensing patents; obtaining external technology; developing partnerships for specific project activities; and generating spin-offs.

In the innovation process, the funnel includes four main stages: ideation, research, development, and commercialization. Inside the funnel are signaled the steps of the proposed model that integrates IM and AC. Here, it is worth mentioning that each step does not necessarily begin and end at the same stage of the innovation process, and so the passage inside the funnel is also dashed to represent such a situation.

Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that the widest part of the funnel represents the largest number of ideas and projects in the early stages of the innovation process, and that until the market is reached, the end of the funnel is smaller, also representing that not all ideas become innovations, for the most diverse reasons. Therefore, from left to right, the projects start in the research stage, requiring exclusively internal R&D efforts, and/or, with the collaboration of external partners, advance to the development phase that already denotes a greater maturity and consistency of the project. The arrival at the commercialization stage implies that many filters (screening) have already been applied internally. Only the most promising innovations are ultimately brought to the market, as they are initially perceived to have greater chances of success. During the ideation stage, prior knowledge and the identification of needs strengthen the activities inherent to the creative process of formulating new ideas. Considering the interaction with the external environment, it is important to recognize that ideas can originate from both internal and external sources. It is crucial to keep on the radar for new trends and consumer/user behaviors that may indicate needs to be met. Similarly, prior knowledge of the organization can be harnessed to generate insights from new projects. Knowledge about a market in which the organization already operates can generate new insights for adaptation in new markets.

The research stage is also characterized by the organization’s strong relationship with its stakeholders and external environment. The participation of universities through scientific research that generates results for the initial stages of product/service development and innovative processes to be implemented by organizations stands out. At this stage, potential AC is evidenced through the acquisition and assimilation of knowledge. These are essential factors for initiating the project, verifying its technical feasibility, and assessing whether the organization’s existing conditions are adequate. This process requires analyzing the knowledge to be acquired and generating new knowledge resulting from its assimilation. The organization and storage of information are supported in this activity by allowing timely access to useful and appropriate information at the project stage. Information support, in this case, may or may not be through its own systems or contracted by the organization, but it also includes all support in basic formats that the organization already uses, such as free platforms.

In the development stage, the acquisition and assimilation of knowledge still occurs and may also be associated with a moment of greater maturity of the project in technical terms, with a bias of approximation to the market potential. At this stage, fundamental activities include analyzing and assessing the business’s potential and viability. This characterizes the phase of potential AC, in which knowledge is transformed and applied to support a practical understanding. Activities such as prototyping and testing with potential customers or users typically come into focus during this phase. Additionally, the use of information and the adoption of adaptive behaviors are closely related to the sharing of knowledge.

The inter-organizational sharing of information is necessary in the context of working in partnerships. As Davenport and Prusak (2000) points out, the best exploitation environment is one in which everyone performs data collection and then shares the information obtained. Collaboratively defining an organization’s informational requirements helps raise awareness that information is valuable; the correct format makes it easier to distribute.

Therefore, this task is also important for exchanging knowledge between partner organizations. The exchange of ideas and information promotes a dynamic process of information flow. To the extent that organizations establish partnerships to develop new products and services, their partners’ knowledge is incorporated in the same context. From this connection, new knowledge can be generated.

It is expected that new products, services, and/or processes will result after the development stage, following the natural course of a project that has followed the intended stage. It should also be considered that some projects, even those in a more advanced stage, may not proceed to the commercialization stage of the market. In this case, the organization may obtain other results, such as learning from the project development cycle, the realization of partnerships that may be continued or intended in other projects, the development of patents that although not being used at that time may be commercialized and/or used later, or learning about new markets and consumer profiles.

When analyzing the proposed model, it is important to highlight that the IM process and the stages of AC are enhanced while enhancing the development of the open innovation environment in organizations. It is also possible to affirm that the concepts of IM, AC, and prior knowledge investigated here can be considered multidimensional constructs and that the different stages of IM and AC can generate innovation results.

6. CONCLUSION

The theoretical model that integrates IM and AC in open innovation results from a cyclical and non-linear process. That means IM → ACAP → Open Innovation. It was found that the different stages of IM and the routines created for developing AC need constant dialogue and access to the external environment to promote the proper functioning of open innovation practices, which can also be affected by other external factors. The stages of IM and ACAP can occur at different stages of the open innovation process.

Thus, this study contributes to the existing theories initially conceived for their linear characteristic. In this article, we propose that IM flows and the stages of acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and application of knowledge can occur recursively and not necessarily following the order previously defined when it comes to open innovation processes.

This study also reinforces the understanding of managers who adopt and implement open innovation practices, bringing ways to systematize the innovation process with attention to the ‘information’ resource as support for AC. We understand that many routine actions are performed nowadays without a systematization that prevents better results or even inhibits the continuity of partnerships and collaborations in the face of experiences that will not occur as expected.

The importance of this conceptual model lies in its ability to bridge gaps between the fields of IM, AC, and open innovation, providing a structured approach to understanding how these elements interact within innovation projects. By integrating the procedural model of information and the AC framework, the model offers a comprehensive perspective on how organizations can effectively manage information flows and enhance their ability to recognize, assimilate, and apply new knowledge. This synthesis not only supports the theoretical understanding of these concepts but also has practical implications, helping organizations optimize their innovation processes, improve decision-making, and ultimately enhance their competitiveness in an increasingly knowledge-driven economy.

In summary, the practical implications of the conceptual model presented in this study emphasize its potential to serve as a systematic framework for organizations implementing open innovation. By combining IM and AC, the model supports organizations in managing information flow more effectively, enhancing their ability to acquire, assimilate, transform, and apply new knowledge considering open innovation practices. This structured approach could facilitate better decision-making, boosts innovation outcomes, and aids in developing sustained competitive advantages.

Considering the plan to instrumentalize the theoretical model, some referrals are foreseen in the continuity of this study and can be mentioned here: 1. Validate the conceptual model proposed here from empirical studies; 2. Empirically assess the importance of IM, AC, and the impact on the innovative performance of organizations; 3. Investigate in more depth the nonlinearity of IM and AC in the context of open innovation with organizations from different areas of activity; and 4. Establish partnerships with companies interested in participating in the pilot development of the applicable instruments.

REFERENCES

, (2023) Open innovation: Are absorptive and desorptive capabilities complementary? International Business Review, 32, 101865 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101865.

, , (2024) Managing knowledge flows within open innovation: Knowledge sharing and absorption mechanisms in collaborative innovation Cogent Business & Management, 11, 2351832 https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2024.2351832.

(1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage Journal of Management, 17, 99-120 https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108.

, (1997) Writing narrative literature reviews Review of General Psychology, 1, 311-320 https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.1.3.311.

, , , (2020) SMEs embedded in collaborative innovation networks: How to measure their absorptive capacity? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 159, 120196 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120196.

Cacaly, S., Coadic, Y. F. L., Pomart, P. D., & Sutter, É. (2008). [Dictionary of information]. Armand Colin. French. https://www.amazon.com/Dictionnaire-linformation-Serge-Cacaly/dp/2200351321

, (2010) Knowledge absorptive capacity: New insights for its conceptualization and measurement Journal of Business Research, 63, 707-715 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.04.022.

, (2006) In search of complementarity in innovation strategy: Internal R&D and external knowledge acquisition Management Science, 52, 62-82 https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0470.

, (2006) Beyond high tech: Early adopters of open innovation in other industries R&D Management, 36, 229-236 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2006.00428.x.

, (1990) Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 128-152 https://doi.org/10.2307/2393553.

de Albuquerque, S. F., & de Araújo Júnior, R. H. (2014). [Morphology to represent the needs of management information]. Em Questão, 20(2), 166-187. Portuguese. https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/EmQuestao/article/view/42855

, (2023) The implementation of inbound open innovation at the firm level: A dynamic capability perspective Technovation, 122, 102659 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102659.

, , , , (2023) The role of collaborative human resource management in supporting open innovation: A multi-level model Human Resource Management Review, 33, 100942 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100942.

, (2008) Exploring the antecedents of potential absorptive capacity and its impact on innovation performance Omega, 36, 173-187 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2006.06.012.

, , , , (2020) From closed to open: A comparative stakeholder approach for developing open innovation activities in SMEs Journal of Business Research, 119, 230-244 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.08.016.

Guedes, W., & Júnior, R. H. d. A. (2014). [Study of similarities between the mathematical theory of communication and the documentary cycle]. Informação & Sociedade, 24(2), 71-81. Portuguese. https://periodicos.ufpb.br/index.php/ies/article/view/16498

, (2011) Untangling dynamic and operational capabilities: Strategy for the (n)ever-changing world Strategic Management Journal, 32, 1243-1250 https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.955.

, , (2015) Does open innovation apply to China? Exploring the contingent role of external knowledge sources and internal absorptive capacity in Chinese large firms and SMEs Journal of Management & Organization, 21, 594-613 https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2014.79.

, , (2006) The reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and rejuvenation of the construct Academy of Management Review, 31, 833-863 https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.22527456.

, (2019) The roles of absorptive capacity and cultural balance for exploratory and exploitative innovation in SMEs Journal of Business Research, 94, 137-153 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.10.052.

, (2018) Evolution of the open innovation paradigm: Towards a contingent conceptual model Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 132, 284-298 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.02.014.

, , , (2023) Creating and capturing value from open innovation: Humans, firms, platforms, and ecosystems California Management Review, 65, 5-21 https://doi.org/10.1177/00081256231158830.

, (2009) Absorptive capacity, its determinants, and influence on innovation output: Cross-cultural validation of the structural model Technovation, 29, 859-872 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2009.05.010.

(2016) Managerial ties and open innovation: Examining the role of absorptive capacity Management Decision, 54, 2256-2276 https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2016-0161.

, (2022) The linkage between open innovation, absorptive capacity and managerial ties: A cross-country perspective Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7, 100167 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100167.

Patterson, W., & Ambrosini, V. (2015). Configuring absorptive capacity as a key process for research intensive firms. Technovation, 36-37, 77-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2014.10.003

Pavão, G. R., Zonatto, V. C. d. S., Degenhart, L., & Bianchi, M. (2023). [Effects of information sharing, knowledge transfer and organizational capabilities on the relationship between knowledge management and performance]. Sociedade, Contabilidade e Gestão, 18(1), 128-155. Portuguese. https://doi.org/10.21446/scg_ufrj.v0i0.52432

, , , (2022) How firms use inbound open innovation practices over time: Evidence from an exploratory multiple case study analysis R&D Management, 52, 548-563 https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12500.

(1948) A mathematical theory of communication The Bell System Technical Journal, 27, 379-423 https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x.

, , (2010) Building absorptive capacity to organise inbound open innovation in traditional industries Technovation, 30, 130-141 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2009.08.004.

, (2013) Research collaboration and R&D outsourcing: Different R&D personnel requirements in SMEs Technovation, 33, 142-153 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2012.11.005.

, (2008) Beyond industry-university links: Sourcing knowledge for innovation from consultants, private research organisations and the public science-base Research Policy, 37, 1079-1095 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.04.003.

, , , , , (2024) The Oxford handbook of open innovation Oxford University Press Opening up open innovation: Drawing the Boundaries, pp. 51-64, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780192899798.013.4

, , (2023) Empirical analysis of the influencing factors of knowledge sharing in industrial technology innovation strategic alliances Journal of Business Research, 157, 113635 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113635.

(1984) A resource-based view of the firm Strategic Management Journal, 5, 171-180 https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050207.

, (2002) Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension The Academy of Management Review, 27, 185-203 https://www.jstor.org/stable/4134351.

(2017) Benefiting from open innovation: A multidimensional model of absorptive capacity Journal of Product Innovation Management, 34, 269-288 https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12361.