Emoji Votes: Predicting Kathmandu’s 2022 Mayoral Election via Facebook Sentiment

Shreejana Gnawali (Global College, Kyungsung University, Busan, Korea)

Abstract

As political engagement is increasingly migrating to social media platforms, understanding the emotional dynamics embedded in online reactions has become critical to interpreting voter behavior. This study explores how Facebook’s reactions function as affective signals of voter sentiment and predictive indicators of electoral outcomes, using the 2022 Kathmandu metropolitan mayoral election. Drawing on emotion theory and affective information behavior, the research analyzes 322 Facebook posts related to the campaign from three leading candidates: Balen Shah, Keshav Sthapit, and Sirjana Singh, focusing on emoji-based reactions, shares, and comments. Sentiment scores were computed using a weighted classification of emojis, and predictive potential was assessed through rank-order analysis and correlation with actual vote shares. The result reveals a positive correlation between preelection sentiment indicators and electoral outcomes. Balen Shah, who led in both emotional engagement and final vote count, demonstrated how affective online support can signal electoral strength. Time-truncation and unweighted scoring further validated the robustness check. Additionally, text analytics highlight Shah’s resonance with majority voters and his alignment with calls for systemic change, contrasting with mixed sentiment toward the latter two. This study contributes to the growing literature on digital political engagement by demonstrating that emoji reactions can serve as reliable proxies for public sentiment in emerging democracies. The findings suggest practical implications for political strategists, campaign managers, and communication agencies seeking to understand and respond to digital sentiment in real time.

- keywords

- social media platform, sentiment analysis, emoji reaction, election campaign, voter behavior, affective information behavior

1. INTRODUCTION

The rise of social media has significantly reshaped the landscape of political communication, enabling new forms of engagement between political actors and the public. Platforms such as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and TikTok have become instrumental in political discourse. They not only disseminate information but also shape political campaigns (Nahon & Hemsley, 2013; Tumasjan et al., 2010), civic participation (Boulianne, 2020), political protest (Theocharis et al., 2015), and voter behavior through affective digital cues shaping voter attitudes. Rather than functioning merely as content distribution systems, these platforms create dynamic affective environments where users signal support, dissent, or ambivalence in real-time.

Among social media platforms, Facebook stands out due to its widespread adoption and rich set of emotional affordances. It’s seven emoji reactions: like, love, care, ha-ha, wow, sad, and angry (Fig. 1), offer researchers a granular and interpretable set of affective signals (Tian et al., 2017). These reactions enable users to communicate the intensity and character of their emotional stance toward political messages, providing a valuable lens through which to observe affective information behavior (AIB). The latest studies integrating emoji reactions with natural language processing and computer vision techniques have shown that these multimodal expressions can serve as reliable proxies for voter sentiment (Khan et al., 2025; Wisniewski et al., 2020). Compared to traditional surveys, social media data offers real-time, large-scale insights into public sentiment, with the potential to decode how individuals emotionally process and respond to political content (Muraoka et al., 2021; Saifeddine & Abdellatif Chakor, 2024).

Despite growing interest in affective digital engagement, much of the existing literature remains concentrated in Western contexts (Chambers et al., 2015) or larger democracies, such as India, leaving regions like Nepal relatively underexplored. Nepal’s increasing digital adoption offers a compelling context to explore how AIB unfolds in emerging democracies. Following its transition from a monarchy to federal republic, Nepal has witnessed rapid growth in political discourse on digital platforms, particularly Facebook (Bhattarai, 2023). Recent studies have documented the use of social media for youth engagement (Wagle, 2024) and political mobilization (Kharel, 2024), but few have analyzed how Facebook’s emotional reactions serve as behavioral indicators of political alignment.

This study seeks to address that gap by reframing Facebook emoji reactions as affective signals within the broader framework of AIB. Using the 2022 Kathmandu mayoral election as a case, we examine how the digital expression of emotions correlates with real-world electoral outcomes. This research seeks to: (1) examine affective patterns expressed through Facebook emoji reactions expressed toward political candidates; (2) evaluate the predictive power of sentiment polarity and user engagement to actual vote shares; (3) explore how nonpartisan emotional engagement challenges traditional party-based political alignment; and (4) demonstrate how emoji-based expressions predict electoral outcomes in Nepal’s evolving political landscape.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Social Media Platforms and Digital Political Engagement

Social media platforms have reshaped political engagement by directly enabling emotionally charged interactions between candidates and voters. Platforms such as Facebook, X, and TikTok are no longer passive information outlets. They function as an active space where political sentiment is expressed, shaped, and amplified in real time (Boulianne, 2020; Persily & Tucker, 2020).

Emotional reactions have emerged as a key metric of user sentiment on social media platforms. Tian et al. (2017) showed that Facebook emoji reactions offer interpretable affective signals, which are often more reliable than text-based sentiment. Bond et al. (2012) found that emotionally resonant content on Facebook could influence real-world voter turnout, underscoring the behavioral power of digital emotion. Several studies link social media sentiment to electoral outcomes. Tumasjan et al. (2010) and Haryanto et al. (2019) demonstrated how X and Facebook sentiment mirrored election results in Germany and Indonesia, respectively. Muraoka et al. (2021) found that love and anger reactions to party posts correlated with public support across 79 democracies. These findings suggest that emoji reactions are more than mere expressions, as they serve as behavioral signals with predictive potential.

In the context of South Asia, Agarwal and Bansal (2020) examined Facebook posts during India’s 2017 state election and found that sentiment polarity correlated with candidate performance. In Nepal, Bhattarai (2023) noted Facebook’s growing role in political socialization, particularly among youth, while Upreti et al. (2025) found that emotional engagement on Facebook correlated with electoral success in the 2022 parliamentary election. Their study revealed patterns in voter sentiment, messaging strategies, and emotional tone. However, challenges including misinformation and echo chambers can skew sentiment (Guess et al., 2020), and in Nepal, limited digital access may affect representativeness (Kharel, 2024).

Despite this emerging body of work, comprehensive analyses of Facebook-based affective signaling in Nepal remain limited. In particular, the role of emoji reactions and emotional cues as behavioral indicators of political alignment remains underexplored, highlighting the need for further research into AIB in the country’s digital political sphere.

2.2. Emotion Theory and Affective Information Behavior

Understanding how emotions shape information processing is crucial for interpreting digital political behavior. For classifying emotional responses, emotion theory provides the psychological foundation, while AIB explains how these emotional states shape the way individuals interact with information in real-world and digital environments.

Ekman (1993)’s theory of six universal emotions (happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust) offers a widely accepted framework for decoding affective expression. Similarly, Plutchik (1965)’s wheel of emotions illustrates how primary emotions blend into complex affective states that influence perception, communication, and decision-making. In digital spaces like Facebook, emoji reactions such as love, care, anger, or sadness serve as proxies for these emotional expressions, allowing users to communicate affective responses to political content on a scale.

To further explore this emotional analysis with information science, this study draws from the field of AIB, which explores how emotional states influence information seeking, processing, and use. Kuhlthau (1991)’s information search process (ISP) model was among the first to integrate affect, identifying phases of uncertainty, optimism, confusion, and relief during search behavior. Nahl (2007) later expanded this with a tripartite model incorporating affective, cognitive, and sensorimotor dimensions. Savolainen (2015) emphasized the everyday, contextual nature of affective engagement, where emotions guide not only what information individuals attend to, but also how they evaluate and act upon it.

In this study, Facebook emoji reactions are conceptualized not just as affective signals but as manifestations of collective emotional information processing. Users reacting to political posts on social media are engaging in a form of public affective behavior—an expression of sentiment that reflects not only individual preferences but also broader political association. By aggregating and analyzing millions of such reactions, we argue that these aggregated affective signals function as behavioral indicators, offering predictive insight into electoral outcomes. This integration of emotion theory with AIB thus enables a more holistic understanding of how affect drives both digital engagement and real-world political decision-making.

3. RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

This study explores the extent to which Facebook reactions serve as a real-time indicator of voter sentiment and electoral outcomes based on the 2022 Kathmandu metropolitan election in Nepal. Due to Nepal’s growing social media penetration and its evolving democratic landscape (Kharel, 2024), this context presents a unique opportunity to examine how digital engagement reflects political preferences. Thus, the central research question guiding this study is: To what extent do Facebook emoji reactions reflect AIB during mayoral political campaigns, and how might they serve as predictors of collective political sentiment?

To address this question, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Facebook emoji reactions reflect users’ emotional responses toward political candidates during electoral campaigns.

H2: Pre-election emotional expressions on Facebook can predict electoral outcomes.

H3: Emoji reactions signal voter sentiments towards candidates, independent of party affiliation.

These three hypotheses are tested through the analysis of emoji reactions, post shares, and comments on Facebook posts related to campaigning from April 26 to May 10, 2022, focusing on three prominent candidates: Balen Shah, independent; Keshav Sthapit, Communist Party of Nepal-United Marxist-Leninist (CPN-UML); and Sirjana Singh, Nepali Congress (NC). By focusing on Nepal, this research extends the global discourse on social media’s electoral influence, which is often centered on Western contexts, and contributes to understanding digital politics in emerging democracies. Insights from the study could inform campaign strategies, enhance electoral predictions, and shape policies for digital governance, offering lessons for South Asia and beyond.

4. METHODOLOGY

This study employs a multi-step methodology designed to analyze Facebook engagement as a behavioral signal of voter sentiment and electoral outcomes. Our approach integrates sentiment classification, engagement normalization, predictive analysis, and robustness check. This section is organized into three subsections: (1) Data collection and sample, (2) Sentiment categorization and scoring, and (3) Predictive signal assessment.

4.1. Data Collection and Sample

We collected data from the official Facebook pages of three major mayoral candidates in the 2022 Kathmandu metropolitan election: Balen Shah (independent), Keshav Sthapit (CPN-UML), and Sirjana Singh (NC). These mayoral candidates were selected due to their prominence and public engagement throughout the campaign. Given the capital city’s central political role and strong digital infrastructure, the election attracted a highly engaged online audience.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and politician background of the three main candidates in the 2022 Kathmandu mayoral election. Balen Shah, a 35-year-old independent candidate and structural engineer with a background in rap music, appealed strongly to younger, digitally active voters through his outsider image and reform-oriented message. In contrast, Keshav Sthapit, a 69-year-old seasoned politician from the CPN-UML with prior experience as mayor (1997-2006), drew support from older, traditional party members. Sirjana Singh, aged 63 and representing the NC, came from a well-established political lineage and was supported primarily by unions and party-affiliated constituents.

Table 1

Candidates’ demographics

| Name | Balen Shah | Keshav Sthapit | Sirjana Thapa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 35 years (born in 1990) | 69 years (born in 1956) | 63 years (born in 1962) |

| Education | Master’s degree | Bachelor’s degree | Master’s degree |

| Profession | Rapper, structural engineer, politician | Politician | Politician |

| Party affiliation | Independent | Communist Party of Nepal-United Marxist Leninist | Nepali Congress |

| Political experience | - | Past mayor (1997-2006) | Former youth leader/chairperson (women’s union) |

| Party founded | - | 1991 | 1950 |

| Total membership | - | 855,000 (2021) | 870,106 (2021) |

| Election date | 13 May 2022 | ||

| Constituency | Kathmandu Metropolitan | ||

| Votes cast/total | 61,767/159,906 | 38,117/159,906 | 38,341/159,906 |

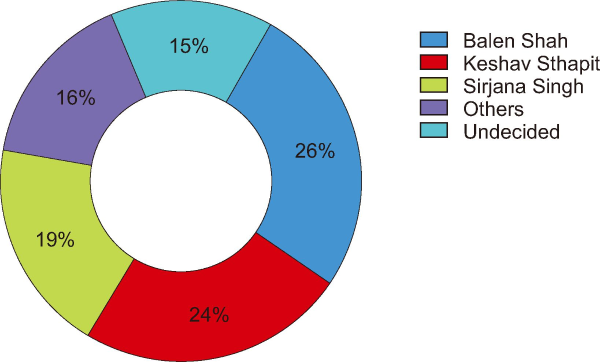

Earlier, a national newspaper conducted an opinion poll in the days before the election (Setopati Team, 2020). The poll results showed that Shah, the independent candidate, was in the lead, followed by Sthapit from the CPN-UML party in second place, and Singh from the NC party in third place. The poll also revealed minimal support for other candidates, reflecting the preferences of voters who had not decided yet (Fig. 2).

To mimic real-time predictive analysis, we retrieved Facebook posts, reactions, comments, and shares from April 26 to May 10, 2022, excluding the final three days to avoid post hoc bias. Preprocessing included the removal of spam, duplicates, and non-emotive content to ensure a high-quality dataset for sentiment evaluation.

4.2. Sentiment Categorization and Scoring

The initial task involved categorizing Facebook emojis into five impressions: very positive, positive, neutral, negative, and very negative expressions (Table 2), drawing on the emotional models identified by Ekman (1993) and Plutchik (1965), which primarily delineate three types of emotions. We assigned a weighted sentiment score to each reaction type based on its implied emotional value into positive (e.g., love, care, and like), negative (e.g., sad and angry), and neutral (e.g., ha-ha and wow) reactions. These emojis were deemed universally applicable to any text, audio, video post, or share on the platform. To further ensure reliability, we calculated the weights using a pilot study with human annotators, achieving an inter-rater agreement.

Table 2

Description of Facebook emoji

| Emojis | Description | Impression |

|---|---|---|

| Love | Users show strong support for the Facebook post | Very positive |

| Care | Users show support for the Facebook post | Positive |

| Like | Users show pleasure towards the Facebook post | Positive |

| Ha-ha | Users show sarcasm, but the feeling is neutral | Neutral |

| Wow | Users show surprise, but the feeling is neutral | Neutral |

| Sad | Users were upset by the Facebook post | Negative |

| Angry | Users were completely upset by the Facebook post | Very negative |

Users typically employ the ‘like’ emoji when expressing agreement and positive sentiment on a post. The ‘care’ reaction is used to convey empathy, kindness, and understanding, and it is also inclined towards positive feelings. Expressing greater affection, users utilize the ‘love’ emoji, considered twice as strong as the like and care emoji, to ensure an accurate calculation of positive polarity on Facebook.

On the other hand, ‘sad’ and ‘angry’ reactions were used to express disapproval or frustration. Given its heightened intensity, the ‘angry’ emoji was assigned double the weight of ‘sad.’ Emojis such as ‘ha-ha’ and ‘wow’ were treated as context-dependent: ‘ha-ha,’ often used sarcastically in political discourse, was classified as negative, while wow was considered neutral to mildly positive, particularly when found in combination with other favorable reactions. Utilizing these data, the overall positive and negative sentiments were calculated accordingly as follows:

Table 3 illustrates the sum of all seven emojis, including followers, posts, comments, and shares. Balen Shah had 30 posts, Keshav Sthapit had 168 posts, and Sirjana Singh had 124 posts on their respective Facebook walls. The cumulative number of posts amounted to 322, and all the emotions and reactions, including followers associated with each post and candidates, were meticulously analyzed.

Table 3

Facebook posts and reactions

| Candidate (party) | Balen Shah (independent) | Keshav Sthapit (CPN-UML) | Sirjana Singh (NC) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Followers | 1,400,000 | 209,000 | 13,000 | 1,622,000 |

| Posts | 30 | 168 | 124 | 322 |

| Facebook engagement | ||||

| Comments | 81,041 | 6,629 | 9,127 | 96,797 |

| Shares | 39,875 | 2,150 | 5,185 | 47,210 |

| Likes | 884,000 | 122,288 | 96,127 | 1,102,415 |

| Emotion reactions | ||||

| Love | 668,700 | 4,897 | 8,257 | 681,854 |

| Care | 84,465 | 399 | 444 | 85,248 |

| Ha-ha | 2,179 | 6,068 | 510 | 8,757 |

| Wow | 5,786 | 159 | 82 | 6,027 |

| Sad | 153 | 39 | 14 | 206 |

| Angry | 69 | 180 | 43 | 292 |

Using the first formula and data from Table 3, we calculate the total positive and negative sentiments in Table 4 below.

Table 4

Total positive and negative sentiments

| Candidates | Total positive sentiments | Total negative sentiments |

|---|---|---|

| Balen Shah (independent) | 2,311,651 | 2,470 |

| Keshav Sthapit (CPN-UML) | 132,580 | 6,467 |

| Sirjana Singh (NC) | 113,167 | 610 |

| Total impact | 2,557,398 | 9,547 |

Based on the data of total positive and negative sentiment, each post’s net sentiment polarity was calculated as:

Sentiment polarity

4.3. Predictive Signal Assessment

To evaluate the predictive potential of affective engagement of Facebook, we employed a combination of interpretable, signal-based approaches grounded in sentiment metrics and pre-election data. These included:

(i) Rank-order comparison between digital sentiment metrics and vote shares.

(ii) Pearson correlation to quantify the strength of association.

Key indicators such as average sentiment polarity, engagement rate (e.g., reactions, shares, comments per 1,000 followers), and overall emotional reaction scores were computed for each candidate and compared against their final vote percentage. To further strengthen this analysis, we applied the logarithmic sentiment index developed by Oh and Kumar (2017), which expresses the ratio of positive to negative reactions:

This framework enabled a focused assessment of whether Facebook-based affective expressions collected before elections could meaningfully signal voter support. The strong alignment between sentiment indicators and electoral outcomes highlights the potential of social media data for early-stage electoral forecasting and behavioral analysis in digital political environments.

5. DATA ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

5.1. Findings from Emotions and Engagement

Table 5 reveals great contrasts in both emotional intensity and engagement patterns across the three mayoral candidates. Balen Shah has an exceptionally high emotion score of 1,429,539, compared to just 17,450 and 16,021 for Sirjana Singh and Keshav Sthapit, respectively. This shows many folds of difference, suggesting that Shah not only generated more interactions, but also evoked far stronger emotional responses among Facebook users. His posts elicited highly affective reactions, indicating that followers were not merely passive consumers of content but deeply engaged participants.

Table 5

Engagement rate and sentiment rate

| Candidates | Emotion score | Engagement rate | Reactions rate | Shares per post | Comments per post |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balen Shah | 1,429,539 | 980 | 980 | 1,329 | 2,701 |

| Keshav Sthapit | 16,021 | 243 | 243 | 12.8 | 39.5 |

| Sirjana Singh | 17,450 | 355 | 355 | 42.8 | 73.6 |

In terms of engagement rate and reactions per 1,000 followers, Shah again dominated, with values of 980 outpacing Singh (355) and Sthapit (243) by fair margins. This indicates that his emotional appeal translated into active engagement on a per-follower basis, further reinforcing the notion of authentic resonance between candidate and audience.

Notably, Shah also led in shares per post (1,329) and comments per post (2,701), both orders of magnitude higher than Singh (42.8 shares, 73.6 comments) and Sthapit (12.8 shares, 39.5 comments). High sharing rates suggest that Shah’s content was not only engaging but amplified organically through network effects, reaching a broader audience and reinforcing campaign visibility. The volume of comments further reflects a high level of public discourse and two-way interaction surrounding his candidacy.

Together, these metrics reflect a candidate whose campaign successfully leveraged affective communication and participatory momentum on Facebook. The scale and depth of digital engagement observed for Shah support the broader finding that emotion-driven social media activity is a meaningful predictor of electoral support.

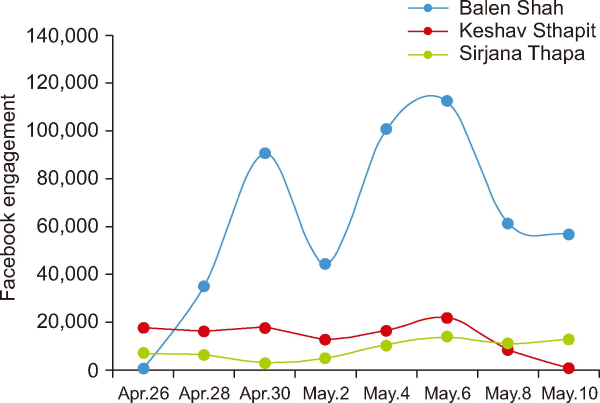

Similarly, Fig. 3 shows the average Facebook engagement (likes, shares, and comments) for each candidate, calculated over two-day intervals from April 26 to May 10, 2022. Balen Shah began his campaign on April 28 but quickly gained traction, consistently leading with significantly higher engagement, peaking at nearly 120,000 on May 4 before declining later. In contrast, Sthapit and Singh showed relatively low and stable engagement, with minor fluctuations. The stark contrast highlights Shah’s strong digital presence and sustained public interest during the campaign period, aligning with his eventual electoral success.

5.2. Findings from Predictive Signals

To assess the predictive strength of Facebook reactions, we compare each candidate’s pre-election sentiment indicators with their actual vote share.

A rank-order comparison was conducted to evaluate the alignment between pre-election sentiment metrics and actual electoral outcomes based on both average sentiment polarity and the logarithmic sentiment index. Balen Shah consistently ranked first across all three dimensions—average polarity (1.00), sentiment index (6.84), and vote share (38.64%), demonstrating a strong alignment between emotional engagement and electoral success. Although Singh and Sthapit’s vote shares were nearly identical (23.83% and 24.03%, respectively), their positions were reversed compared to their sentiment ranks (Table 6). Despite this minor discrepancy, the overall ranking demonstrates strong alignment between affective digital engagement and electoral performance, reinforcing the predictive value of pre-election Facebook sentiment signals.

Table 6

Sentiments vs. voting results

| Candidates | Net sentiment polarity | Sentiment index | Actual vote share |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balen Shah | 1.00 (1st) | 6.84 (1st) | 38.64% (1st) |

| Keshav Sthapit | 0.91 (3rd) | 3.02 (3rd) | 24.03% (2nd) |

| Sirjana Singh | 0.99 (2nd) | 5.22 (2nd) | 23.83% (3rd) |

To further evaluate the relationship between online sentiment and electoral outcomes, a Pearson correlation was conducted using both the sentiment index and net sentiment polarity. The correlation between the log-transformed sentiment index and vote share was r=0.81, indicating a strong positive association. This metric reflects the relative dominance of positive sentiment over negative. A moderate correlation was observed between net sentiment polarity and vote share (r=0.58), suggesting that the overall emotional tone of user reactions (particularly the balance between positive and negative sentiment) was meaningfully aligned with electoral performance. This was evident in Shah’s case, where high user engagement and affective support corresponded closely with voting outcomes.

These findings suggest that Facebook sentiment signals (net polarity and sentiment index) offer a reliable behavioral proxy for electoral support when measured prior to elections. However, minor rank mismatches between sentiments and vote share, as seen between Singh and Sthapit, indicate that offline factors such as party affiliation, demographic outreach, or mobilization strategies may still influence voting outcomes beyond what is captured digitally.

5.3. Robustness Checks

To ensure the reliability of our findings, we conducted two robust validation tests. First, we conducted a time-truncation analysis by excluding the final three days of Facebook data (May 8-10) from the dataset. After truncating, 201 posts remained across all candidates. Keshav Sthapit had the most posts, followed by Sirjana Singh and Balen Shah, consistent with the post distribution in the full dataset. We then ran the sentiment analysis on the truncated dataset and compared the results with the actual vote share. While the correlation between sentiment analysis and vote share declined slightly (r=0.78), the ranking of candidates and the overall predictive direction remain unchanged. This suggests that the model’s predictive strength is not solely dependent on last-minute surges in online engagement but instead reflects more stable affective patterns throughout the campaign (Jaidka et al., 2019).

Second, we tested the robustness of our sentiment scoring method by removing the emotion-based weighting assigned to specific emoji reactions. In this unweighted model, all reactions were treated equally, so each emoji contributed to one unit regardless of its affective intensity. While this simplified approach still yielded a strong correlation between sentiment polarity and vote share (r=0.62), the predictive precision declined slightly compared to the weighted model. This result reinforces the theoretical and empirical value of emotion-weighted scoring, which captures varying degrees of affective expression and improves the sensitivity of the sentiment-vote relationship (Giuntini et al., 2019; Tian et al., 2017).

These checks confirm that our results are not dependent on a specific time window and emoji weighting scheme, strengthening the claim that Facebook emoji reactions are robust behavioral signals of electoral sentiment (Hauthal et al., 2019).

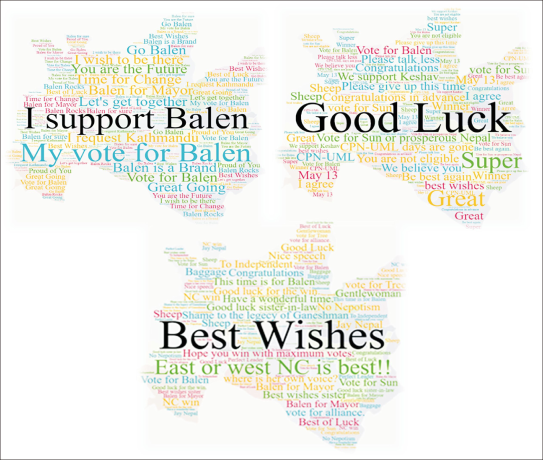

5.4. Findings from Text Analytics

We conducted text analytics of Facebook comments directed toward mayoral candidates Balen Shah, Keshav Sthapit, and Sirjana Singh to uncover the most frequently mentioned messages, terms, and sentiments associated with each. Using techniques such as word clouds and sentiment analysis, we gained valuable insights into the narratives and conversations of the electorate. Word clouds offer a visually intuitive method for highlighting commonly used terms, making them crucial for identifying key public conversations.

We began by analyzing the word cloud for Balen, who received the most comments—76,141 in total, which is 85% more than the combined total for the other two candidates. Most of these comments were positive, with phrases like ‘I support Balen,’ ‘my vote for Balen,’ and ‘time for change’ appearing frequently (Fig. 4). Additionally, many comments from users included terms like ‘youth’ and similar phrases, such as ‘vote for youth,’ ‘youth for change,’ ‘youths of Kathmandu,’ and ‘Balen rock.’ Balen’s posts primarily featured photos from campaign rallies and live videos. He was the first to announce his mayoral candidacy and start a Facebook campaign. Judging by the comments and rally videos, it appears that he had many young supporters. On the negative side, Shah was underestimated for his independent candidacy without the support of any political party, which is a significantly necessary factor in Nepal’s partisan political landscape.

Fig. 4

Word clouds for Balen Shah (top left), Keshav Sthapit (top right), and Sirjana Singh (bottom).

In the word clouds for Keshav Sthapit and Sirjana Singh, we observed a noticeable concentration of support for their rival, Shah, with comments like ‘vote for Balen’ and ‘this time it is Balen’ appearing occasionally. Despite this, there were numerous positive comments for both candidates. Keshav Sthapit’s posts received comments such as ‘good luck,’ ‘congratulations,’ and ‘be the best again,’ reflecting his previous tenure as mayor two decades earlier from 1997 to 2006, as he sought this position for a second time. Similarly, Sirjana Singh’s posts attracted comments including ‘best wishes,’ ‘Jay (hail) Nepal,’ ‘congratulations,’ and ‘gentlewoman.’ However, despite support from various unions, including those representing teachers, students, traders, and drivers, both candidates also faced substantial criticism. Keshav Sthapit was criticized with comments like ‘please talk less’ and ‘you are not eligible,’ while Singh encountered remarks such as ‘no nepotism,’ and ‘shame to Ganesh Man.’ Mrs. Singh comes from a prominent political background, with her husband serving as a parliamentarian and her father-in-law, Ganesh Man, a significant figure in Nepal’s political history. She was often criticized for alleged candidacy bargaining and partisan politics. Additionally, users who expressed support were derogatorily referred to as ‘jholye’ (porter) and ‘bheda’ (sheep). The term ‘jholye’ is used to describe people who blindly carry a politician’s ideology or actions, while ‘bheda’ refers to those who follow their leaders or the crowd without much knowledge.

Our analysis shows that in the days leading up to the election, there was a high volume of positive comments, particularly targeting Shah, and negative comments targeting Keshav Sthapit and Sirjana Singh, which may have contributed to the polarity for them. Unfortunately, Facebook posts about election rallies and meetings by the latter two major political candidates were either sparsely commented on or met with negative sentiments.

6. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study marks the first empirical attempts to analyze Nepal’s mayoral election through the lens of Facebook emoji reactions and behavioral signals of voter sentiment, interpreted with the AIB framework. Nepal’s evolving digital landscape and unique political dynamics make this investigation timely and significant, contributing to broader understandings of digital political engagement in emerging democracies (Boulianne, 2020; Boulianne & Larsson, 2023). By examining how emoji reactions reflect emotional information processing, this study advanced AIB by showing how digital affective signals shape voter decision-making (Kuhlthau, 1991; Savolainen, 2015).

The findings support all three hypotheses. First, Facebook emoji reactions reflect users’ emotional responses to political candidates, serving as proxies for AIB processes such as emotional evaluation and preference formation (Nahl, 2007). Sentiment distribution and polarity scores closely aligned with voting behavior, supporting studies that endorse social media sentiment as a reliable proxy for public opinion (Ceron et al., 2023; Sandoval-Almazan & Valle-Cruz, 2020). Similar findings from India (Rita et al., 2023) reinforce this, although Jungherr et al. (2012) caution that social media users may not fully represent the electorate, suggesting emoji reactions be interpreted as behavioral signals rather than precise forecasts.

Second, the predictive value of engagement was evident, with candidates showing higher positive sentiment and interactions (reactions, shares, comments) performing better at the ballot box. Rank order analysis (Balen at number 1 on all) and Pearson’s correlation (r=0.81 for sentiment index, r=0.58 for polarity) confirm that emoji-driven engagement predicts vote shares, echoing Bond et al. (2012) and Oh and Kumar (2017). However, contextual factors like limited digital access, misinformation, or offline mobilization may mediate online sentiments in different environments (Sandoval-Almazan & Valle-Cruz, 2020).

Third, emotional engagement extended beyond party lines, with independent candidate Balen Shah generating the most intense positive reactions due to his perceived integrity and issue alignment. This suggests that emoji reactions reflect AIB’s assessment of candidates’ authenticity, and this perceived authenticity, as interpreted through AIB, subsequently influence voter decisions beyond party loyalty (Savolainen, 2015). Shah’s passionate, issue-focused communication (Gautam, 2022) aligns with research on personalized engagement (Enli & Skogerbø, 2013), with parallels to nonpartisan campaigns such as Emmanuel Macron’s in France (Cole, 2022). However, party identity remains influential where echo chambers persist (Barberá, 2015).

Overall, this study highlights emoji reactions as AIB-driven indicators, offering diagnostic and predictive insights into voter sentiment in Nepal. Timer-truncation and unweighted sentiment analyses ensured robust results, providing a methodological foundation for future studies in emerging democracies.

7. IMPLICATIONS FOR THE STUDY

This study highlights the importance of AIB in understanding digital political engagement on social media platforms, contributing to both AIB and political communication. Drawing from emotion theory (Ekman, 1993; Plutchik, 1965) and the AIB framework (Kuhlthau, 1991; Nahl, 2007; Savolainen, 2015), the findings demonstrate that emotionally charged expressions, specifically Facebook emoji reactions, serve as reliable behavioral predictors of electoral outcomes. The positive correlation between pre-election sentiment polarity and vote share validates the role of collective emotional information processing in shaping voter decision-making, advancing AIB by showing how digital affective signals reflect and predict real-world behaviors.

This study’s results extend Kuhlthau (1991)’s ISP model by illustrating how emotions like enthusiasm (expressed via love and like reactions) or dissatisfaction (angry and sad reactions) guide users’ interactions with political information, influencing their voting decisions. Similarly, Nahl (2007)’s emphasis on affective states as drivers of information behavior is supported by the high engagement rates and emotional intensity observed for Balen Shah, whose campaign resonated with users’ desires for change and authenticity. By demonstrating how emoji reactions serve as proxies for collective emotional processing, this study enriches the AIB framework, showing that these reactions are not merely expressions but predictive indicators of behavioral decision-making in democratic contexts (Fulton, 2009; Lopatovska & Arapakis, 2011).

The findings offer multifaceted practical implications for political strategists, campaign managers, and political communication agencies in digitally connected societies. First, social media platforms such as Facebook offer real-time feedback on voter sentiment based on emoji reactions (love, care, like, sad, wow, ha-ha, and angry), enabling dynamic adjustment to campaign messaging. Political strategists can employ analytics tools like Hootsuite or Sprout Social to monitor sentiment shifts, craft emotionally resonant content that fosters stronger voter connections, and adjust messaging in real time. For instance, they might emphasize empathetic narratives when “sad” reactions spike to build trust and engagement effectively.

Second, Balen Shah’s success as an independent candidate, driven by strong emotional appeal, demonstrates that affective engagement is not tied to political party affiliation, aligning with AIB’s findings on the role of emotional authenticity in shaping public trust and engagement (Savolainen, 2015). This trend suggests that modern electorates, particularly those active in digital space, respond more positively to candidates who communicate clearly to show genuine concern on social issues, rather than relying on traditional party-based rhetoric. Campaign managers can focus on sincere, issue-based communication that centers a candidate’s vision and relatable appeal. Practical steps include posting a video about their effort to address local healthcare access or hosting live Q&A sessions to directly engage with voters’ concerns.

Third, this study signals a broader shift from traditional clientelist and identity-driven politics to more personality-driven nonpartisan politics. Emotional expressions on platforms like Facebook indicate that voters increasingly value accountability, transparency, and competence over traditional loyalty-based appeals. Political actors or communication agencies should adapt messaging strategies, accordingly, focusing on relevant emotionally grounded narratives that build trust and engagement. This could involve crafting authentic stories around candidates’ values and actions, emphasizing competence and responsiveness to public concerns, and leveraging emotional cues to connect with audiences on a personal level.

8. LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSION

This research has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, Facebook users do not always truthfully represent their sentiments and behaviors in political posts, thus raising doubts about whether reactions to Facebook posts truly reflect their voting behavior. Moreover, citizens often criticize politicians regarding accountability, scandals, and campaigns. Online activities tend to elicit more impulsive and aggressive behavior, which may influence sentiments towards political parties. Secondly, contextual factors such as the political inclinations of voters, Internet accessibility, and candidates’ political backgrounds were not considered, factors that could influence voters’ decisions and sentiments. Future studies could explore the varied effects of these contextual elements.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of affective engagement in digital political spaces, using the 2022 Kathmandu metropolitan election as a case to explore how Facebook reactions function as behavioral signals of voter sentiment. By analyzing over 300 campaign-period posts and millions of emoji reactions, the study provides evidence that Facebook engagement, particularly affective expressions, can offer insight into public sentiment and predict electoral outcomes.

As the use of social media in political communication continues to expand, this study highlights the significance of interpreting emotional engagement not only as online behavior, but as part of broader affective information practices. Facebook reactions, when analyzed thoughtfully, can serve as indicators of political alignment, campaign resonance, and shifting voter priorities, making them a vital tool for political analysis and strategy in diverse democratic contexts.

REFERENCES

, , , , , (2020, May 5-7) Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Volume 1: ICEIS SciTePress Exploring sentiments of voters through social media content: A case study of 2017 assembly elections of three states in India, 596-602, https://doi.org/10.5220/0009517105960602

(2023) The use of social media for political socialization in Nepal: An effectiveness analysis of platforms The Outlook: Journal of English Studies, 14, 46-59 https://doi.org/10.3126/ojes.v14i1.56656.

, , , , , , (2012) A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization Nature, 489, 295-298 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11421. Article Id (pmcid)

(2020) Twenty years of digital media effects on civic and political participation Communication Research, 47, 947-966 https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218808186.

, (2023) Engagement with candidate posts on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook during the 2019 election New Media & Society, 25, 119-140 https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211009504.

, , (2023) Facebook as a media digest: User engagement and party references to hostile and friendly media during an election campaign Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 20, 454-468 https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2022.2157360.

, , , , , , , , , (2015, September) Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing Association for Computational Linguistics Identifying political sentiment between nation states with social media, 65-75, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/D15-1007, Article Id (pmcid)

(2022) Understanding Macron's political leadership and his impact on French politics https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2022/05/03/understanding-macrons-political-leadership-and-his-impact-on-french-politics/

(1993) Facial expression and emotion American Psychologist, 48, 384-392 https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.4.384.

, (2013) Personalized campaigns in party-centred politics Information, Communication & Society, 16, 757-774 https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.782330.

(2009) The pleasure principle: The power of positive affect in information seeking Aslib Proceedings, 61, 245-261 https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530910959808.

(2022) Kathmandu's 'Balen Phenomeno' https://nepalitimes.com/opinion/comment/kathmandu-s-balen-phenomenon

, , , , , , (2019) How do I feel? Identifying emotional expressions on Facebook reactions using clustering mechanism IEEE Access, 7, 53909-53921 https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019. .

, , (2020) Exposure to untrustworthy websites in the 2016 US election Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 472-480 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0833-x. Article Id (pmcid)

, , , , , (2019) Facebook analysis of community sentiment on 2019 Indonesian presidential candidates from Facebook opinion data Procedia Computer Science, 161, 715-722 https://doi.org/j.procs.2019.11.175.

, , (2019) Analyzing and visualizing emotional reactions expressed by emojis in location-based social media ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 8, 113 https://www.mdpi.com/2220-9964/8/3/113. Article Id (other)

, , , (2019) Predicting elections from social media: A three-country, three-method comparative study Asian Journal of Communication, 29, 252-273 https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2018.1453849.

, , (2012) Why the pirate party won the German election of 2009 or the trouble with predictions: A response to Tumasjan, A., Sprenger, T. O., Sander, P. G., & Welpe, I. M. "Predicting elections with Twitter: What 140 characters reveal about political sentiment" Social Science Computer Review, 30, 229-234 https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439311404119.

, , (2025) Sentiment analysis of emoji fused reviews using machine learning and Bert Scientific Reports, 15, 7538 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92286-0. Article Id (pmcid)

(1991) Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user's perspective Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42, 361-371 https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199106)42:5<361::AID-ASI6>3.0.CO;2-#.

, (2011) Theories, methods and current research on emotions in library and information science, information retrieval and human-computer interaction Information Processing & Management, 47, 575-592 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2010.09.001.

, , , (2021) Love and anger in global party politics: Facebook reactions to political party posts in 79 democracies Journal of Quantitative Description: Digital Media, 1 https://doi.org/10.51685/jqd.2021.005.

(2007) Social-biological information technology: An integrated conceptual framework Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58, 2021-2046 https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20690.

, , , (2020) Social Media and Democracy Cambridge University Press Conclusion: The challenges and opportunities for social media research, pp. 313-331, https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/232F88C00A1694FA25110A318E9CF300Article Id (other)

(1965) What is an emotion? The Journal of Psychology, 61, 295-303 https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1965.10543417.

, , (2023) Social media discourse and voting decisions influence: Sentiment analysis in tweets during an electoral period Social Network Analysis and Mining, 13, 46 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-023-01048-1.

, , (2024, April 23-25) Artificial intelligence, big data, IOT and block chain in healthcare: From concepts to applications Cham: Springer Systematic literature reviews in political marketing: Behavior, influence, and trust in the era of big data and artificial intelligence, 112-126, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-65018-5_11

(2015) Cognitive barriers to information seeking: A conceptual analysis Journal of Information Science, 41, 613-623 https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551515587850.

Setopati Team (2022) Setopati projection: Balen Shah to be elected Kathmandu Mayor https://en.setopati.com/political/158478 Article Id (other)

, , , (2015) Using Twitter to mobilize protest action: Online mobilization patterns and action repertoires in the Occupy Wall Street, Indignados, and Aganaktismenoi movements Information, Communication & Society, 18, 202-220 https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.948035.

, , , , , , (2017, April) Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Social Media Association for Computational Linguistics Facebook sentiment: Reactions and emojis, 11-16, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/W17-1102, Article Id (pmcid)

, , , (2010) Predicting elections with Twitter: What 140 characters reveal about political sentiment Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 4, 178-185 https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v4i1.14009.

, , , (2025) Decoding digital campaigns: A multi-method analysis of Facebook posts during 2022 parliamentary elections in Nepal Asia Pacific Journal of Information Systems, 35, 195-215 https://doi.org/10.14329/apjis.2025.35.1.195.

(2024) Helsinki, Finland: Arcada University The effect of social media on result of election in metropolitan city: Special focus on Kathmandu, Nepal (master's thesis), https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/865306

, , , (2020) Happiness and fear: Using emotions as a lens to disentangle how users felt about the launch of Facebook reactions ACM Transactions on Social Computing, 3, Article 20 https://doi.org/10.1145/3414825.

- Received

- 2025-03-30

- Revised

- 2025-06-11

- Accepted

- 2025-06-27

- Published

- 2025-09-30

- Downloaded

- Viewed

- 0KCI Citations

- 0WOS Citations