- P-ISSN 2799-3949

- E-ISSN 2799-4252

During the 17th and 18th centuries, many Vietnamese people from the Ngũ Quảng region (the present-day Quảng Bình, Quảng Trị, Huế, Đà Nẵng, Quảng Nam, and Quảng Ngãi in the Central region) migrated and settled in today’s southern Vietnam, bringing with them many Confucian values related to family and clan organization, especially the concept of filial piety and ancestor worship. Due to the particularity of the immigration situation and living environment in the new frontiers, the ancestor worship, which had been full of Confucian flavor, gradually changed in the direction of “reorganization” and have become a simple yet meaningful collective ritual dedicated to early ancestors during the immigration periods. This article uses Eric Hobsbawm’s (1992) “the invention of tradition” theory, Maurice Halbwachs's (1983) collective memory theory, and Fredrik Barth's (1969) rational choice theory to analyze and synthesize ethnographic field data sources on cúng việc lề (routined clan-ancestor anniversary) mainly collected in Long An Province (a provinve in the Mekong Delta) to demonstrate that the tradition of ancestor worship in southern Vietnam is not only considered a way to give thanks and commemorate the dead, but also, in the special context of immigration, a form of reconstructed Confucian ritual that consolidates family lineage and empowers the living culturally.

NGUYEN Ngoc Tho is an Associate Professor of Cultural Studies and is currently senior faculty member of the Institute of Leadership Development, Vietnam National University–Ho Chi Minh City. He was a visiting scholar at Sun Yat-sen University, the Harvard Yenching Institute, Harvard University's Asia Centre, Boston University, and Brandeis University. He is the author of seven books and over 50 journal articles.

NGUYEN Tan Quoc, MA in Cultural Management, currently Vice Chairman, Long An Provincial Department of Culture, Sport, and Tourism. Nguyen Tan Quoc is the author of the book The Ngũ Hành Goddess festival in Long Thượng (Cần Giuộc, Long An) (2022) and a number of research articles in folk culture published in Vietnam.

JDTREA 2025,4(2): 105–130

On the wild bank of the Vàm Cỏ Đông River 1, the Lê family spread an old and rough woven mat and put simple food and cooked wild vegetables on old plates and bowls as offerings to the early ancestors on the ground. An incense burner, a glass of white wine and a cup of green tea are solemnly placed at the north end - the direction from which their early ancestors once migrated to this land from the central and northern regions. An old man wearing a robe and turban solemnly lit three incense sticks and recited prayers. They worship the family's early common ancestors, those who left their homes in central Vietnam to migrate south and found villages in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in a collective ritual known as “cúng việc lề (routine clan-ancestor anniversary)”. This begs the question: what specifically is cúng việc lề?

The author, Phan Thị Yến Tuyết, described “cúng việc lề (also called cúng vật lề/routine-object sacrifice, cúng lề/routine sacrifice) as a traditional sacrificial ritual formed by the Vietnamese people during their `marching to the South' movement and found village in the southern region, and has become a custom: ( Phan 1991 , 7). This kind of custom is not available in North and Central Vietnam.

The term “lề (routine)” has been explained by Huỳnh Tịnh Của (1974) in Quốc Âm Tự Vị (Vietnamese Dictionary) as an “old habit” or “old custom” of certain places or certain communities. Accordingly, cúng việc lề is a special custom in southern Vietnam to commemorate and thank the early immigrant ancestors who left their homelands in the north and central Vietnam to settle and establish villages in southern Vietnam in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The purpose of holding this custom is to recall life during the pioneering period, remember and pay gratitude to the ancestors in the original place, identify the family tree, and tighten the relationship with relatives in the new homeland. Unlike traditional clan anniversaries that are common in Vietnamese culture, cúng việc lề organizers do not invite people outside the clan to participate; the descendants of the clan remember their clan annual cúng việc lề services and respectfully return to attend. In 2014, the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism decided to recognize this sacrificial custom as a national intangible culture, naming it “cúng việc lề”, and considered it a custom unique to the Mekong Delta region. The Vietnamese people are originally a nation that respected Confucian ethics and principles; they have strong ancestral traditions and solemn ancestor remembrance. Why do Long An people worship their ancestors in such a place with desolate scenery and food that in most other sacrificial rites would be considered too poor to be offered?

There are quite a few systematic research projects or articles that delve into the cúng việc lề rituals. Short essays include Phan Thị Yến Tuyết's (1991) “Tín ngưỡng cúng Việc lề- một tâm thức về cội nguồn của cư dân Việt khẩn hoang tại Nam Bộ” (Cúng việc lề - the sense of seeking the roots of the Vietnamese people to found the southern land), Sơn Nam's (2004) “Cúng việc lề ở Nam Bộ”, Nguyễn Hữu Hiếu's (2004) “Cúng việc lề - Một tín ngưỡng mang đậm dấu ấn thời khai hoang của lưu dân ở Nam Bộ” (Cúng việc lề: A belief with the imprint of the southern Vietnamese immigration period), and Nguyễn Trung Hiếu and Mai Thị Thu's (2023) “Tục cúng việc lề của người Việt huyện Thại Sơn tỉnh An Giang” (The cúng việc lề custom of Vietnamese people in Thoại Sơn District, An Giang Province). These are the four main resources. However, the general descriptions and preliminary generalization of these articles cannot satisfy readers, because cúng việc lề worship is a special custom that needs to be decoded and learned from many different perspectives such as history, culture, psychology, anthropology, and so on.

In addition, Chapter Two (“Belief and Religion”) of the book Địa chí Long An (Long An Provincial Geography) briefly mentioned that cúng việc lề is a traditional custom in some special Long An clans. They hold this event on a designated day to honor their ancestors in the early periods and strengthen clan ties in their new homelands ( Thạch and Lưu eds. 1989 ). Besides, the provincial intangible cultural heritage survey carried out by the Long An Provincial Museum in 2006 gave a preliminary and comprehensive understanding of Long An's customs and beliefs, among which, cúng việc lề custom is described in statistical detail for the first time. One of the authors of this article participated in the Museum project in 2005; therefore, having survey information from 2005 helps compare with field survey data from 2022 to 2023 onward, allowing us to contextualize the overall changes in cúng việc lề custom (if any).

Our study found that ritual worship is truly popular in the Đồng Nai–Vàm Cỏ rivers system (north of the Mekong River Basin), even though some cases are found in the southern part of the Mekong River ( Nguyễn and Mai 2023 ). The Đồng Nai–Vàm Cỏ river basin is the area where Vietnamese first moved south, opened lands, and established villages during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; the special background of early immigration and village establishment gave rise to cúng việc lề sacrificial rituals. Long An province (the Vàm Cỏ Rivers subsystem) can be considered the heartland of the cúng việc lề custom in the region. The area south of the Mekong River was expanded by the Mạc family from Hà Tiên ( Li 1998 ; Cooke and Li 2004 ; Chen 2008 ; Ang 2019 ) and was later consolidated by Vietnamese families from north of the Mekong River; by this time, the family clan system and institutions in the area had stabilized, the cúng việc lề custom may have existed, but is not prevalent south of the Mekong River.

Together with Đồng Nai and Gia Định (the present-day Ho Chi Minh City), the Vàm Cỏ Rivers area of Long An Province was settled early by Vietnamese immigrants in the late seventeenth century. Following the orders of the Nguyễn Lord, Marquis Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh went south to formalize the territory of present-day southern Vietnam and named it the Đồng Nai—Gia Định Region in 1698. By 1832, King Minh Mạng established Tân An central village at the heart of the Vàm Cỏ Rivers area. In 1867, the French colonialists divided the land of Long An into two counties (Tân An and Phước Lộc) and a part merged into the neighbouring Chợ Lớn province. Starting from 1 January 1900, Long An was redivided into Tân An Province and Chợ Lớn Province. Until July 1957, Long An Province was established on the basis of Tân An Province and parts of Chợ Lớn Province, which remains stable to this day. Long An was also the birthplace or revolutionary activity area of early meritorious officials (such as Mai Công Hương, Nguyễn Huỳnh Đức, Mai Tự Thừa in the eighteenth and early 19th centuries) and patriotic heroes participating in all major anti-French struggles of the late 19th and early 20th centuries such as Nguyễn Trung Trực, Nguyễn Văn Tiến, Nguyễn Văn Quá, Đỗ Tường Phong, Đỗ Tường Tự, (local anti-French heroes), Phan Phát Sanh (a member of the local Tiandihui Secret Society), Trần Chánh Chiếu and Bùi Chi Nhuận in the Đông Du Movement 2, and so on. The people of Long An adopted the spirit of “sinh vi tướng, tử vi thần (living as a general and dying as a god)” to treat these officials and heroes specially; therefore, in many cúng việc lề sacrifices, people particularly praise their merits.

This research applies Eric Hobsbawm's (1983) “the invention of tradition” theory, Maurice Halbwachs's (1980) collective memory theory and Fredrik Barth's (1969) rational choice theory to study the origin, characteristics and nature of cúng việc lề sacrificial custom and to argue that whether or not the Vietnamese people are influenced by Confucianism, the tradition of ancestor worship has been motivated by care and gratitude for the deceased rather than as a ritual form that specially conferred cultural authority and prestige for the living. The data for this study mainly come from two sources: 1) the work analysis and evaluation results of the Long An Provincial Museum project on cúng việc lề custom in 2005; and 2) the ethnographic field survey data in the Vàm Cỏ Rivers area in 2022 and 2023.

Traditional Vietnamese Ancestral Worship

Before the seventeenth century, Vietnamese mainly lived in the Red River Delta and north of the central region. Vietnam's traditional ancestor worship beliefs were formed in prehistoric times and were institutionalized (or formalized) under the influence of Confucianism, especially during the Lê Dynasty in the 15th century and beyond. This belief has both spiritual value (praying for the incarnation of deceased ancestors and seeking for ancestral protection), cultural and social value (“drinking water to remember the source (uống nước nhớ nguồn),” passing on the family line, educating filial piety and other ethics) ( Trần, 2001 ).

Traditional Vietnamese and today's North Vietnamese place great emphasis on family clan traditions and relationships (in addition to cultural traditions and relationships between village families). Some villages were formed based on an extended family clan, for example, Lê Xá Village was composed of all members of the Lê family, and Chử Xá Village was composed of members of the Chử family. Some villages were made up of inter-family clan connections. The two elements of family clan tradition and village cohesion are closely intertwined, making each village a kingdom with its own system of village customs ( Trần 2001 ). As a result, the Vietnamese have established a complete family clan system (ancestral shrine, clan principle, clan genealogy, clan death anniversary ceremonies) and attach great importance to ritual forms, clan hierarchy, ritual systems and male authority (see Buttinger 1972, 15, 22; Kim Định 1973 , 172).

The Vietnamese ancestor worship was first founded on the foundation of 1) memory, respect and gratitude to ancestors 3, and 2) the concept of soul and body 4; accordingly, the soul lives on after death and can occasionally visit descendants of the family. Ancestor worship at this time only reflected the original concept of filial piety and had not yet been institutionalized by mainstream ideology.

Entering the period of Chinese occupation (1st century CE to 10th century CE) and the period of independent monarchies (10th century CE to 1945 CE), the Vietnamese accepted certain ideas of the Three Teachings from China, among which Confucianism had the most profound influence on the local ancestor worship ( Nguyen 2016 ). The imperial families, with strong support from central and local Confucian scholars, formalized customs and rituals in what James Watson (1985) called “standardization” or “orthopraxy” (see Pham 2009; Nguyễn 2019). However, Vietnamese Confucianism (based mainly on Neo-Confucianism) is considered moderate and open; under any circumstance, Confucianism and Taoism have had to adapt to Buddhism ( Duong 2004 300; Phan 2000 , 80–87; Woodside 2002 , 117, 127, 131; Vo and Nguyen 2020 , 59–83). Therefore, although the veneer of Vietnamese ancestor worship has been branded with new values, the concepts of respect and gratitude for ancestors remain the main pillars of this belief.

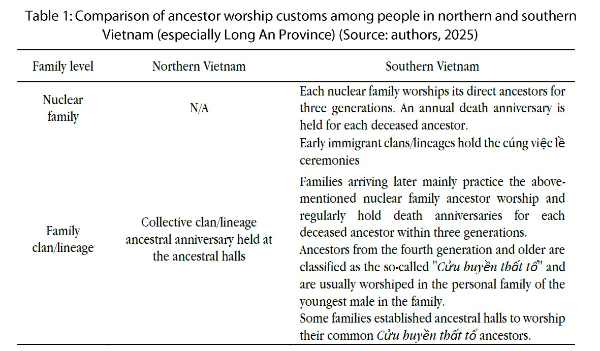

The custom of ancestor worship has been institutionalized and ritualized, and has become a family rites 5 category or a formal behavioral norm in the family, with etiquette principles and regulations, as well as the form of sacrifice and ceremony. Generally speaking, annual sacrificial activities are held every year for the first to third generation ancestors, while ancestors of the fourth generation and earlier are collectively known as Cửu huyền thất tổ and are worshiped at the ancestral shrine. The ancestral hall has a hierarchical system, including the main line (the oldest male family) and the clan branches. The collective death anniversary of the main clan is held earliest and on the largest scale. Every branch and every family has a responsibility to fully participate and contribute in order. Subsequently, each sub-clan takes turns to hold sub-clan death anniversary ceremonies. The family sets up a clan tablet system and attaches it to the family clan tradition and honor.

Therefore, clan rituals are also an opportunity to show off family clan prestige and honor. The Vietnamese courts used standardized customs and rituals to civilize minority areas and new frontiers, including today's southern Vietnam ( Ang 2019 ). However, this “civilization policy” did not take effect until the social and political system of this new frontier gradually stabilized at the end of the eighteenth century. Cúng việc lề sacrificial custom was established in southern Vietnam before the end of the eighteenth century and was only practiced among early immigrant families in the Đồng Nai—Vàm Cỏ subregion.

Cúng việc lề as a Special Version of the Ancestral Beliefs of the Southern Vietnamese

The southern Vietnamese people, including the Long An Vietnamese, are descendants of “Nam tiến (Marching to the South)” immigrants from different times. The process of marching south is divided into two steps, that is, the first step is to march from the north to the central region, and the second step is to march from the central region to the south. In 1600, Nguyễn Hoàng, a bureaucrat of the Lê Dynasty, and his people went to the Thuận Quảng region (present-day Huế-Đà Nẵng), established the Kingdom of Đàng Trong (early Cochinchina) and deepened Vietnamese ties with the larger world of Southeast Asia which “enabled him to establish a new vision of being Vietnamese distinguished by the relative freedom from the Vietnamese past and the authority justified by appeals to that past” ( Taylor 1993 , 64). C. P. Fitzgerald stated that “they [the southern Vietnamese] became less amenable to the distant central government, more independent in their thinking and way of life” (1972, 29). Jeffrey Richey downgraded the importance of Confucian values in the southern Vietnamese tradition while elevating the role of Buddhism and folk cultural institutions ( Richey 2013 , 68). Ancestor worship has thus given rise to many new forms appropriate to immigrant backgrounds, including cúng việc lề.

The Nguyễn Lords (1600–1789) and, later, the Nguyễn Dynasty (1802–1945), promoted Confucian orthodoxy but mainly “used it as means of territorializing and civilizing the new lands” ( Nguyen and Nguyen 2020 , 87). As Confucianism declined and popular Buddhism became more pronounced, Vietnamese immigrants to the Southern from the Huế-Quảng Nam region fell into a state of cultural and ideological ambiguity. Immigrants from the Red River Delta (North Vietnam) to the Huế-Quảng Nam region (northern part of the Central) had been organized mainly in families/village collectives, while immigrants from the Huế-Quảng Nam region to the south were mainly of small-family size; therefore, the traditional clan culture and closed rural culture have largely collapsed, paving the way to the emergence and the rise of “newly-invented traditions. 6”

In southern Vietnam, the customs, rituals, and Confucian value systems related to family and clan traditions do not have suitable conditions to be maintained and developed like in the Red River Delta or the Huế-Quảng Nam region. Families in southern Vietnam still retain the custom of annual ancestor worship, but it is held separately within each nuclear family. Ancestors who died within three generations are worshiped, but there are no clear systems and regulations within the family clan. Many families do not build a common ancestral hall or record family trees, except those who migrated in the 20th century. The person responsible for organizing the death anniversary ceremony is the youngest son of the family, unlike the tradition in the north and the central region where it is the eldest son who must perform this task. Before the clan memorial day, family members take turns inviting relatives, neighbors, friends, and colleagues to the party after the ceremony; this makes the family ancestors' memorial days both a family atmosphere and a spirit of neighborhood unity. Has the Confucian tradition within the framework of traditional Vietnamese families and clans really entered a state of deconstruction in the South?

As mentioned above, the land in the northeastern part of southern Vietnam (Đồng Nai—Gia Định—Định Tường) was first reclaimed, and the main population was immigrants from the Huế-Quảng Nam region (see also Lê, 2022). Both Trịnh Hoài Đức (2005) in Gia Định Thành Thông Chí (Gazetteer of Gia Định Citadel, c. 1818) and members of the Nguyễn Dynasty History Compilation Bureau in Đại Nam Nhất Thống Chí (Veritable Records of the Great South) all wrote that the residents in this area “each family has its own customs,” except the cúng việc lề custom in large family clans. It is worth noting that after the eighteenth century, families who later immigrated to the south did not hold this sacrificial ceremony [cúng việc lề], perhaps because the economy, culture, and society were stable at this time, and the national administrative structure was stable, collective family clan so death anniversaries gradually transformed into individual death anniversaries of ordinary families. Why did early immigrant families start holding cúng việc lề sacrificial ceremonies?

Before Vietnamese exploration (around the mid-seventeenth century), much of what is now southern Vietnam was barren or flooded, except for the indigenous settlements in the upper reaches of the Đồng Nai River and the Saigon River area, as well as the Khmer villages on higher terrain such as the coastal sand dunes or the Seven Hills of the Lower Mekong Delta. Zhou Daguan (周達觀, vn. Châu Đạt Quan) in Zhenla Fengtuji (真臘風土記, A Record of the Kingdom of Chenla, written in the 13th century) wrote that much of the lower Mekong delta was filled with wild animals, such as crocodiles, tigers, monkeys and buffalo. Around 1620s, the first group of Vietnamese immigrants came south to the Đồng Nai River, only twenty years after occupying the port of Hội An (from the Chăm people) in the central region. Some families set out from the Đồng Nai River Basin to explore the Saigon River and Vàm Cỏ Rivers (north of the Mekong River). The harshness of nature (floods, wild animals, epidemics, starvation) and social challenges (attacks, looting) claimed many lives. Due to high mobility and poor living conditions, people could only bury the dead roughly and continue to make a living; after a while, people of later generations no longer knew on what day their ancestors had died or where they [the ancestors] had been buried.

However, the mentality of respecting and being grateful to ancestors and the concept that the dead must be sacrificed to in order to avoid becoming wild ghosts became the eternal motivation in the hearts of Vietnamese immigrants at that time. Members of the same lineage began performing collective cúng việc lề rituals on wild riverbanks or on land where their early ancestors had embarked from immigrant ships/sampans. Some families set up sacrificial boats full of sacrifices and push them off the banks of the Vàm Cỏ Rivers to feed the wandering souls who died during the migration process. They worshiped their ancestors who had lived in the central region or who had died on their way south. Every family has its own cúng việc lề rules, which are known only to lineage members in the appropriate space and time. According to our investigation records, the Lê family of Tầm Vu Town in Long An Province is an ancient family, and it has been eleven generations since their ancestors moved south. The details of the cúng việc lề custom as well as its characteristics and significance will be analyzed in detail in the following sections.

Various forms but consistent in meaning

As mentioned above, the Long An Vàm Cỏ Rivers basin is the area with the densest cúng việc lề customs in southern Vietnam. We investigated and learned about the cúng việc lề sacrificial customs of 16 of the most typical families in the area. Preliminary results show that this custom in Long An have various forms and specifications, but its characteristics and significance are very consistent.

Regarding the date of the cúng việc lề sacrifice, we found that each family has its own choice, which is passed down and preserved from generation to generation. Cúng việc lề days can be the death anniversary of the “original ancestors” many generations ago (when they were still in the Central regions, the death anniversary day of the earliest ancestor moving south, the memorial day of a meritorious ancestor, the day to worship the land god, or the day to pray for the whole family (cầu an). Generally speaking, each family clan will choose a fixed day, and clan members at different times will automatically remember and participate in it as part of their duties.

The Ngô family in Kiến Tường Town chose 25 January (the death anniversary of the wife of the first-generation ancestor, Mr Võ Tự Phụng) 7 to be the day of cúng việc lề. The Lê family of Đức Tân Commune in Tân Trụ District chose a day of the land god worship, 18 March. The Nguyễn family in Đức Hòa Thượng Commune, Đức Hòa District chose 16 February, the family's Prayer Day, as the day of cúng việc lề. The Nguyễn family in Thạnh Đức Commune, Bến Lức District makes a living as fishermen, so they designated 10 March as the cúng việc lề day 8. The Lê family in Thanh Phú Commune, Bến Lức District chooses the death anniversary day of a meritorious ancestor, Mr Lê Văn Hy 9, General-in-Chief of Trường Sa Maritime Legion of the Nguyễn Dynasty 10. Some families choose the day of graveyard decoration of December 25 as the cúng việc lề day, such as the Hồ and the Nguyễn families in Long Sơn Commune, Cần Đước District; the Phạm and the Nguyễn in Phước Lại Commune, Cần Giuộc District; the Biện Hữu in Mỹ Lộc Commune, Cần Giuộc District; the Nguyễn and the Đặng in Lợi Bình Nhơn Commune, Tân An City; the Đoàn in Mỹ Thạnh Commune, Thủ Thừa District; the Lê in Bình Thạnh Commune, Thủ Thừa District, and so on. The Nguyễn in Quarter 4, Thạnh Hóa Town They choose the last day of the old year, 30 December, which is also the day that welcomes deceased ancestors home for the lunar New Year festival, as the cúng việc lề day. Many others take the day of sending-off deceased ancestors during the lunar New Year, 3, 4, or 5 January, to be the day of cúng việc lề. Especially, the Nguyễn in Vĩnh Hưng Township and another Nguyễn family in Vĩnh Thạnh Commune, Vĩnh Hưng District (the annually flooding area) choose 5 July, the peak of the annual flood, to hold the cúng việc lề ceremony to facilitate the use of various fish caught in the flood to make sacrifices.

Regarding the space of the cúng việc lề ceremony, the authors of this research found that many families choose to hold cúng việc lề sacrifices in the side of rivers, canals or on wasteland beside village roads, while other families decide to hold the ceremony in family ancestral halls. None of them place offerings on the altar or table; instead, they spread a mat on the ground, place the offerings and a small boat that sails north 11. Especially the ceremony held in the wild recreates the scene of the ancestors who came here to reclaim land and build villages in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Therefore, the space in which the ceremony is held recalls historical and cultural memories associated with the period of marching to the South in pre-modern Vietnamese history. The film Mùa len trâu (“Buffalo Boy”) directed by Nguyễn Võ Nguyên Minh (2005) 12, although some details are a bit exaggerated, uses film art techniques to reflect the heroism of the southern reclamation and settlement period.

Regarding sacrificial offerings, there is a unifying principle among families. All food, cooked or raw, must be as simple as possible, especially if it is close to the food of the early days of immigration. All offerings are regular, mandatory, and cannot be changed over time. During our observations in 2004–2005 and 2022–2023, we found that every family would cook cháo ám, wild-frilled snakeheaded fish (cá lóc nướng trui) and a variety of wild vegetables to venerate their ancestors. Cháo ám is cooked by brown rice with a half-processed raw fish (leaving the fish whole, without cutting off the fins), reflecting the difficult lives of early immigrants who didn't even have kitchen utensils to cook. Usually, three pieces of snakehead fish are grilled whole without cutting them, spread on a banana leaf or lotus leaf on a mat, and served with raw salt. Vegetables, both cooked and raw, are picked from accessible wasteland. Mung bean sticky rice is cooked in whole bean shells and served with a few cubes of solid brown sugar on the side. Fish, shrimp, crab, banana, taro, and wild vegetables were available in Long An could be easily acquired in the early time. It is exactly the case of cultural reproduction as described by Pierre Bourdieu ( Bourdieu 1977 ). When asked why the families had to cook with specific ingredients instead of others, they explained it was because of their ancestors' tastes and dietary preferences. Food containers such as bowls and plates are made from plants grown in homes' yards ( Nguyễn and Nguyễn 2010 ; Nguyễn 2011 ). The people of Long An have two sentences that describe the hard and miserable life of the early residents:

“Cháo ám đựng miểng vùa, tổ tiên khai đường hậu thế;

Rơm đồng trui cá lóc, cháu con cảm đức tiền nhân” (the author collected in 2004).

(Translation: Cháo ám is served in a coconut shell; early ancestors opened up land and villages for future generations;

Snakehead fish is grilled on the rice-straw fire; descendants solemnly express their respect and gratitude to their ancestors).

Depending on the background and family life, many families must prepare some special items as offerings. The Lê family in Đức Tân Commune (Tân Trụ District) served the shrimp salad of twelve “bowls” made by banana tree trunk bark. The Trần family in Bình Tịnh Commune (Tân Trụ District) needs to prepare 100 bánh tét 13 and 100 bánh ít 14, each one as small as the big toe. The Lê family in Khánh Hậu Ward of Tân An City prepare rice cake and some cubes of solid brown sugar. The Phạm in Tân An city downtown prepare a dish of summer roll, 5 spare heads, a dish of three classic sacrifice food (bộ tam sên) 15. The Võ family in Kiến Tường Town need to make a dish of `elephant skin salad', now replaced by pork skin salad, with an elephant-shape pork skin laid on top. The Võ family also places a piece of opium on the offering plate to remind and teach all members to stay away from the drug (because there was once an addict in the family). Both the Phạm family in Tân An and the Võ family in Kiến Tường Town made a living by hunting (in the Đồng Tháp Mười flooded lowlands) in the early days. The Lê family in Thanh Phú Commune (Bến Lức District) serves a plate of raw meat to worship the tiger—`the lord of the forest' (because someone in the family was killed by a tiger)—and constructs a straw human statue with five coconut leaves and five arrows on it, forming the sacred five elements structure to `destroy' and sweep ghosts away. The Nguyễn family in Đức Hòa Thượng Commune (Đức Hòa District) serves additionally a wild-grilled snake, while the Huỳnh family in Bình Tâm Commune (Tân An City) prepares a bowl of water (for the washing of ancestors) and a mirror covered by a piece of red cloth (as mentioned in a Vietnamese proverb “nhiễu điều phủ lấy giá gương (the red cloth fully covers the mirror)”, signifying the family clan consolidation. The Đỗ family in Dương Xuân Hội Commune (Châu Thành District), serves three wild-grilled shrimp on a dish of salad made from wild plants. The Lê family in Đức Tân Commune (Tân Trụ District) serves a tray of candy (made by burnt sticky rice mixed with brown sugar) on wild plants.

The common feature of cúng việc lề sacrificial rituals in Long An is that the ritual performers strive to reproduce the hard life of their ancestors and their journey south to the wilderness. Nowadays, although conditions have improved, many clans and families still spread mats on the ground to prepare for sacrifices. Bowls and plates must be simple (made of clay or wood). The food offerings are sometimes placed on lotus leaves, banana leaves or anthurium leaves, and the chopsticks are made of wild branches. According to regulations, during sacrifices, family members are not allowed to place sacrifices on the altar, nor are they allowed to use luxurious bowls and chopsticks.

There are no written rules for sacrificial rituals; however, some basic principles are applied. The head of the family clan, or the celebrant, dressed in neat robes, presides over the ceremony, pours wine and water, burns incense and prays. Each family's vows are different; the general idea is to remember the great achievements of our ancestors who went through all kinds of hardships to come to this new land and create careers for later generations. The celebrant bows (kowtows) four times, and then each member of the family similarly bows four times in order of family rank. During the ceremony, the Võ family in Kiến Tường Town arranged for men to stand on one side and women to kneel on the ground on the other side. Members of the Đỗ family in Châu Thành District stood on either side of the celebrant with their arms folded in order of family rank, while the celebrant knelt in front of their ancestors and read the eulogy. Members of the executive committee of Tân Xuân commune (Tầm Vu Town, Châu Thành District) perform a bowing ceremony after the prayer ceremony for family descendants. Two anti-French heroic ancestors of the Đỗ family (Đỗ Tường Tự and Đỗ Tường Phong) are worshipped in Tân Xuân Communal House because of their sacrifice in the war against France at the end of the 19th century.

After the incense is all burnt out, the celebrant burns votive paper money as well as paper gold and silver ingots, sprinkles rice and salt, and finally performs a banana raft rafting ceremony on the river to send of the ancestors back to their place. Some families beat gongs and drums or play ritual music during the ceremony (such as the Lê in Bến Lức District, the Võ in Kiến Tường Town, the Đinh in Châu Thành District, the Đặng in Cần Đước District, and so on). What follows is a `communitas' 16 meal enjoyed by the whole family, along with stories of the adventures and achievements of their early ancestors. Cúng việc lề custom thus conveys the generosity, chivalry and humanistic life spirit of generations of the Vàm Cỏ residents.

The Hybridity of Cúng Việc Lề Customs

There are two elements to the Cúng việc về customs that enable them to easily absorb affiliated beliefs/rituals and easily adopted by other spiritual institutions, especially Lunar New Year rituals and popular religions, namely, dealing with the souls/the deceased, and ritual-oriented nature.

Firstly, cúng việc lề sometime is attached to the collective death anniversaries (giỗ hội, or hiệp kỵ) of big family clans in Long An. Like most families in northern Vietnam, some prominent families in Long An also established ancestral halls. They believe that the cúng việc lề ceremony is a collective family anniversary for all deceased ancestors of the family clan and is usually held in the family's ancestral hall instead of choosing a wild venue. Although ancestors of more than four generations (Cửu huyền thất tổ, aforementioned) are enshrined in the ancestral hall, each member family still holds death anniversaries every year to commemorate the direct ancestors of the first to third generations. Arguably, these families' cúng việc lề custom reflects a mixture of both northern Vietnamese traditions and local “newly invented traditions.” In contrast to the northern tradition, this collective family ritual is performed in the form of a cúng việc lề sacrificial ceremony, rather than a Confucianized and well-organized ancestor worship ceremony.

Some families have clear clarification on cúng việc lề rituals and formal death anniversary ceremonies; however, these two rituals are closely related to each other. The Lê family in Thanh Phú Commune (Bến Lức District), the Phạm family in Phước Tuy Commune (Cần Đước District), the Đặng family in Long Trạch (Cần Đước District), and the Nguyễn family in Thạnh Đức Commune (Bến Lức District) first hold a cúng việc lề ceremony outdoors and then hold a formal sacrificial ceremony in the main ancestral hall.

Secondly, cúng việc lề is sometimes amplified and/or extended to perform additional rituals to honor land gods and wandering spirits, or family prayer rituals. The cúng việc lề sacrificial rituals of some family clans are mixed with rituals of sacrificing hero-ancestors. As aforementioned, local heroes such as Nguyễn Huỳnh Đức, Nguyễn Văn Tiến, Nguyễn Văn Quá, Đỗ Tường Phong, Đỗ Tường Tự, Mai Tự Thừa, and others are worshipped and honored in related families' cúng việc lề rituals; some other unrelated family clans also honor local heroes in the ceremony. The Đỗ family in Châu Thành District in their annual cúng việc lề ceremony recalled the merits of two hero-ancestors as follows:

...The country was invaded by the enemy [French], and they felt insecure; like heroes, they swore to worship Thủ Khoa Huân as their general They recruited brave soldiers, gathered agricultural products, sold land, and stood up to follow General Thủ khoa Huân against the French. Messrs. Đỗ Tường Phong and Đỗ Tường Tự used the Bình Cách area and the Long Trì - Bình Dương corridor (Mỹ Tho) as a base of resistance... (collected in 2005).

Although not related by blood, the Nguyễn family of Thạnh Đức Commune (Bến Lức District) has a large part of the memorial eulogy in memory of the hero Nguyễn Trung Trực:

Dear the village guardian god, heroic god, and ancestors, today is March 10, we hold this sacricial ceremony to dedicate General Nguyễn and his soldiers. We pray that our Nguyễn family will be safe, strong, free from illness, and overcome all disasters... (collected in 2022).

The Lê family in Thanh Phú Commune (Bến Lức District) is expected to prepare a wood and paper warship with “cannons” and statues of soldiers on it to represent the heroic deeds of General-in-Chief, Mr Lê Văn Hy, and his Trường Sa Maritime Legion during the early Nguyễn Dynasty (the early 19th century). The boat is taken to the riverway intersection for “launching” after the main ceremony on land.

Thirdly, many families attach a ghost-feeding ritual to a cúng việc lề ceremony. Indeed, people today do not know when and where their ancestors died during the process of marching to the South, and they may think that some of ancestors are now hungry ghosts. Therefore, during the cúng việc lề ceremony, the celebrant often invites wandering spirits and unworshipped warriors to participate. In the cúng việc lề ritual of the Nguyễn family in Thạnh Đức Commune (Bến Lức District), a part of the eulogy is read:

We pay tribute to the fallen soldiers on both sides, the unjust dead, and the unworshipped warriors of the Nguyễn family's past generals. We pray that you will protect and bless us from generation to generation... (collected in 2004).

Apparently, during the Marching to the South movement of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, accidental deaths became common, and the lines between ancestors and ghosts became rather blurred.

Fourthly, cúng việc lề is also an opportunity to pay homage to the land gods and goddesses (Thổ địa, Ngung Man Nương, and so on), early landowners, and the agricultural god (Thần nông). This is a belief originating from the custom of “repaying gratitude to the landowners” of Vietnamese residents in the Huế-Quảng Nam region. According to local spiritual beliefs, the land these families live on once had owners; they worshiped land gods and early landowners, meaning they bought, leased, or temporarily borrowed the land so that their families could live in peace and make a good living. A passage in the eulogy towards the land god of the Nguyễn family in Thạnh Đức Commune (Bến Lức District) describes and follows:

Dear the God of the Land, the God of the River, and the early landowner couple, we pray that our family will always be free from disasters and illnesses from the beginning of the year to the end of the year... (collected in 2023)

Food offered to the land god can be either meat or vegetarian, such as boiled chicken, pig head and pig tail 17, boiled pork, rice, soup, glutinous rice, sweet soup, and so on. Last but not least, many families include the family prayer ritual in a cúng việc lề ceremony. In addition to expressing respect and gratitude to the ancestors, the whole family also performs a collective prayer ceremony at the end of the entire process. The celebrant reads prayers and eulogies while all members bow their heads:

... Ancestors, grandparents, generals and soldiers of the Nguyễn family in all generations! We honestly pay homage to all of you and wish you protect and bless all members of the clan. Please protect us from all kinds of illness and disasters... (Oral eulogy of the Nguyễn family in Thạnh Đức Commune (Bến Lức District, collected in 2022).

Table 1: Comparison of ancestor worship customs among people in northern and southern Vietnam (especially Long An Province) (Source: authors, 2025)

A Ritual-based Family Clan Identification and Consolidation

The ancients once said “there is no ritual/etiquette, there will be no ethics (đạo đức nhân nghĩa, phi lễ bất thành).” Rituals (and customs) have been chosen as a way of conveying family and social morals that family heads and local elites hope to popularize in the community. Ngô Đức Thịnh (2001, 7) once stated that: “Ritual is the environment of religious faith, which contains the lofty and sacred beautiful values that human beings need to pursue: truth, goodness and beauty.”

Firstly, this was the result of rational choices made by early immigrant families in the lands they explored early on, namely, Đồng Nai—Gia Định—Định Tường, including Long An province. In order to adapt to the new environment, early immigrant families actively changed their traditions and behaviors, including ancestor worship and the birth of cúng việc lề ceremony. Therefore, “cúng việc lề” is a newly invented ritual form that is the result of interpreting family traditions and fulfilling filial ethics according to specific circumstances in Long An ( and Southern Vietnam in general).

Cúng việc lề expresses sacred affection for the place of birth, immigrant relatives and the early memories of ancestors. Through the cúng việc lề ceremony, respect and gratitude to ancestors and filial piety are at the core of the ceremony. In addition, family solidarity and hierarchy are tightened. In the eulogy read at the cúng việc lề ceremony, the Đỗ family in Dương Xuân Hội Commune (Châu Thành District), recalled the merits and achievements of their ancestors, as follows: The Đỗ family in Dương Xuân Hội Commune (Châu Thành District) recalls merits and achievements of early ancestor in a paragraph of eulogy read at the cúng việc lề ceremony as follows:

“…Back then, when this land was still in the forest, our ancestors worked hard to cut down trees and grass and establish public farms in Tân Xuân Village. During the day, they took food and water, waded in the mud [to cultivate and catch fish], and didn't care about being bitten by wild leech; at night, they returned to the makeshift house with mud walls and ate simple dinner. Our ancestors were not afraid of hardships and difficulties; they withstood wind, rain and dew, worked under the sun, moon and stars to build the future. By the grace of God, the living career was opened and generations of us can enjoy it today. What respect and admiration! What respect and admiration! …” (collected in Dương Xuân Hội Commune in 2005).

Each family has specific rituals, sacrifices and its own style, but the most common is the representation of memories of the reclamation period. Borrowing the concept from Halbwachs, cúng việc lề ceremony is also an excellent custom to preserve the historical and cultural memory of the early Long An residents ( Halbwachs 1980 ).

Secondly, the style of cúng việc lề ceremony and the details of the sacrifices become intangible signs that identify the family clan, since only clan members know the rules and necessary sacrifices. The above-mentioned Võ family clan in Kiến Tường Town helps clan members recognize their ancestors by offering “elephant skin salad” which reminds present and future generations of their ancestors' hunting traditions during the land opening period. In fact, most of the Vietnamese who went south in the mid-seventeenth century were exiles, wanted criminals, deserters and anti-royal elements. They had no choice but to flee south. To survive without being arrested, many of them had to change their names.

The early immigrant family “invented” cúng việc lề ceremony with specific sacrificial items to allow members of the same clan to recognize their roots, participate in clan's collective activities and consolidate clan relationships in this new land. Many Vietnamese families in the South did not keep family trees. In fact, they “did not dare keep genealogical records” to avoid being caught and killed by officials and soldiers under royal orders. The ceremony also expressed the nostalgia of the early refugees who were hunted by the imperial court for their original homeland, as well as their desire to return home to visit their ancestral graves and relatives. Therefore, the performance of sacrifices in rituals is a sign of recognition, consolidation, preservation and inheritance of the collective family.

Furthermore, the cúng việc lề ceremony can be considered a “secret language” 18 or “secret sign” used to identify families after the diaspora; so, it functions as to preserve and protect family lineage and blood line. The Phan family in Châu Thành District tells a story about a member who lost contact with the entire family for a long time. In 2002, this man finally found his roots by identifying the sacrificial offerings among the Phan family's cúng việc lề sacrifices. Lê Đại Anh Kiệt (2022) calls this ceremony as a “living genealogical record”. If members of the same family clan had to change their surname, they could use this “sacred sign” to avoid intermarrying with each other or getting involved in conflicts.

Historical and Socio-Cultural Significance

From a historical perspective, the cúng việc lề custom reflects part of the history of generations of Vietnamese immigrants exploring Long An and the southern lands, directly reflecting the history of Vietnam's development and territorial expansion during the pre-colonial period. It reflects the process of southern Vietnamese residents gathering different classes of people in new lands over centuries, the process of overcoming harsh natural conditions, and the process of building material and spiritual life. It also demonstrates the bravery, tenacity and endurance of the early South Vietnamese immigrants, and jointly composes a part of national cultural history with high scientific and practical significance.

From a spiritual perspective, cúng việc lề itself and the rituals in it (i.e., ancestor sacrifice and ghost feeding rituals) were once condemned as “superstitious” during the period of high development of post-war socialism ( Endres 2002 , 303–322; Phạm 2009, 8, 14, 149); but now from an interdisciplinary perspective, they are re-evaluated as "thuần phong mỹ tục (beautiful customs and worthy traditions)” which carry family and social morals that are not easily conveyed in textbooks or any secular practice. Since 2005, this custom has been officially recognized as a national cultural heritage and protected. Only by understanding that a community began to open up wasteland, faces hardships and dangers such as wilderness, chaotic living environment, epidemics, disasters, poverty alleviation, etc. can we truly understand and sympathize with them. Apart from rational choice, cúng việc lề customs and their associated activities were the only ways to sustain life in the newly opened lands.

A De-Confucianization Form of Family Tradition in Southern Vietnam?

Vietnam is a country influenced by Confucianism but not entirely Confucian. The impact of Confucianism on Vietnamese culture and life is really not that great compared to China or Korea (see Wolters 1988, 6; Woodside 2002 , 116–143; McHale 2004 ). Within Vietnam, the Confucian imprint of the South further fades (see further Richey 2013, 68–9). As aforementioned, the early immigrants who went south were mainly exiles, wanted criminals, deserters and anti-royal elements. They “escaped” from the strict Confucian framework in which they were “trapped” (see Nguyen and Nguyen 2020, 79–112). In Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư (Complete Annals of Đại Việt, started by Ngô Sĩ Liên in the 15th century, continued by many other writers, and officially published in 1675), state historians Ngô Sĩ Liên seriously criticized Nguyễn Hoàng—the first Nguyễn lord to leave northern Vietnam during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to found Đàng Trong (Kingdom of Cochinchina, present-day Central Vietnam) and expand into the Mekong Delta, for being unfilial because he dared to abandon the ancestral graves and family trees in his hometown. However, Keith Taylor (1993, 64) argued that Nguyễn Hoàng and his people “rejected” the task of being “a good traditional Vietnamese” to shape “another kind of “good Vietnamese” in the Central and then the South.

When evaluating the nature of southern Vietnamese culture, Cao Tự Thanh (1996, 147) concluded that in the South, so-called “Confucianism” is not like actual state Confucianism. 19 Many Confucian schools and Confucius temples were built in southern Vietnam during the Nguyễn Lord period and later (such as Hà Tiên Confucius Temple, Trấn Biên Confucius Temple, Vĩnh Long Confucius Temple, Châu Đốc Confucius Temple, and so on); however, pre-modern Vietnamese Confucian education in the south was different from that in the north, and it appeared to be more practical, more open-ended and situation-based. Under any circumstances, this South Vietnamese characteristic openness and flexibility cannot change or destroy Confucianism; rather, they are establishing or shaping another kind of Confucianism that is more easily accepted and practiced in real life. In daily life today, South Vietnamese might tell anyone that they do not like and do not want Confucian principles (because it narrows and frames their ideology and creativity); however, every family, regardless of social status, integrate Confucian ethical thoughts into family traditions and vividly reflect them in family rituals.

The South Vietnamese do not convey Confucian ethics and morals in textbooks but absorb them into customs and rituals related to their lives. The openness and flexibility of their minds allow them to shape or “invent” a variety of new practices to ensure social order and way of life. Cúng việc lề was “invented” in such a mentality.

In the early stages of the territory expansion and community construction process in southern Vietnam during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (when customs and culture had not yet been institutionalized and normalized), the use of rituals to preserve memories and satisfy spiritual, moral, and social needs was not a deconstruction of traditional Confucianism, but an attempt to make Confucian ethics more adaptable to the new living environment.

Cúng việc lề in Long An province and in the entire South Vietnam is a beautiful custom that combines spirituality and family ethics, ritualized as a status symbol that strengthens family bonds and recalls the history of the immigration period. The cúng việc lề custom is not a de-Confucian form, but a ritualized form of cultural heritage, a tradition and a layer of historical memory that is rather obscure in today's textbooks.

As conveyed in the Confucian saying “there is no ritual/etiquette, there will be no ethics (道德仁義, 非禮不成; in Vietnamese: đạo đức nhân nghĩa, phi lễ bất thành)”, early Vietnamese immigrants in southern Vietnam learned to open up and reorganize their traditions and ideologies to fit the specific context of the newly-opened lands, paving the way for the cultivation of Vietnamese culture in the new frontier. In this process, respect and gratitude to the ancestors who made great sacrifices in the process of land opening and village construction have become the magical glue for the formation and stable development of family clan culture in the region.

1. The Vàm Cỏ river system, including the Vàm Cỏ Tây (Western Vàm Cỏ) and the Vàm Cỏ Đông (Eastern Vàm Cỏ) Rivers, originate from two different sources but merges into one in lower Long An territory. Then, the Vàm Cỏ and Đồng Nai rivers merge into one at the mouth of Soài Rạp.

2. The early 20th elite ideological movement led by Phan Bội Châu (1867–1940), which aimed to send elites to Tokyo to learn Japan's experience in liberating and developing the country.

3. There is a famous Vietnamese proverb that is reminiscent of the tradition of ancestor worship: “Uống nước nhớ nguồn (when drinking water, remember the source)” (Endres 2002, 314).

4. These are similar to Chinese beliefs studied by David Jordan (1972), Arthur Wolf (1974, 131-182) and Robert Weller (1987), the Vietnamese believe that without annual sacrifices, deceased ancestors will become ghosts and will not be reincarnated.

8. In our interviews in 2005 and 2022, many family members verbally stated that this day was the day when the hero Nguyễn Trung Trực bid farewell to his family and led his army to fight against the French in the mid-19th century.

10. In Vietnamese: Tổng đốc Thủy đạo Trường Sa, written on the tablet in the main hall of the Lê family ancestral hall.

11. The north is the direction from which ancestors came during the early waves of immigration in the 17th and 18th centuries.

13.Bánh tét is a special southern Vietnamese and ethnic Khmer rice cake made with beans, ripe bananas or pork in the center (of the cake), wrapped in banana leaves in cylindrical circle shape and cooked for several hours. Bánh tét can be used for many days, convenient for those who travel or work long hours in the rice fields.

14. Bánh ít is made from rice flour, contains mung beans, is wrapped in banana leave and has a cylindrical shape with a triangular base and a pointed top.

15. Three traditional Vietnamese traditional sacrificial foods include a piece of cooked pork, three to five cooked shrimps and a boiled duck egg.

17.Pig head and pig tail are used as offerings, symbolizing good luck from head to toe, from the beginning until the ending.

19.The Vietnamese translation is “Không Nho mà không Nho, không Nho mà là Nho” (Chinese translation: 儒而不儒,不儒而儒).

Duy, Thanh 2019 “Deciphering the cúng việc lề customs on Lunar New Year's 4th Day” [Vietnamese Language Text] “Giải mã tục cúng Việc lề của người dân ngày mùng 4 Tết” https://nld.com.vn/thoi-su/giai-ma-tuc-cung-viec-le-cua-nguoi-dan-ngay-mung-4-tet-2019020810211224.htm. Accessed on Februray 16, 2024.

Lê, Đại Anh Kiệt 2022 The cúng việc lề custom: a secret language of the early land openers [Vietnamese Language Text] “Lệ cúng vật lề: mật ngữ truyền đời của người mở đất.” Người Đô thị (Urbanists), https://nguoidothi.net.vn/le-cung-vat-le-mat-ngu-truyen-doi-cua-nguoi-mo-dat-37539.html. Accessed on 16 February 2024.

Nguyễn, Hữu Hiếu 2004 “Cúng việc lề—a belief with the imprint of the southern Vietnamese immigration period.” Study on the characteristics of southern Vietnamese folk cultural heritage. Hanoi: Khoa học Xã hội [Vietnamese Language Text] “Cúng việc lề- Một tín ngưỡng mang đậm dấu ấn thời khai hoang của lưu dân ở Nam Bộ.” Tìm hiểu đặc trưng di sản văn hóa dân gian Nam Bộ.

2019 “The `standardization' mechanism of East Asian and Vietnamese traditional cultures from a Confucian perspective.” Vietnamese cultural studies 4(190): 3—19 [Vietnamese Language Text] “Cơ chế `chính thống hóa' trong văn hóa truyền thống ở Đông Á dưới nhãn quan Nho giáo.” Nghiên cứu Văn hóa Việt Nam.

Nguyễn, Trung Hiếu and Thị Thu Mai 2023 [Vietnamese Language Text] "Tục cúng việc lề của người Việt huyện Thại Sơn tỉnh An Giang (The cúng việc lề custom of Vietnamese people in Thoại Sơn District, An Giang Province)." Hội Khoa học Lịch sử Bình Dương (Bình Dương Provincial Historical Association), http://www.sugia.vn/portfolio/detail/2035/tuc-cung-viec-le-cua-nguoi-viet-o-huyen-thoai-son-tinh-an-giang.html. Accessed on March 3, 2024.

Watson, L. James 1985 “Standardizing the gods: The Promotion of Tienhou (“Empress of Heaven”) along the South China Coast, 9601960.” In Popular Culture in Late Imperial China, edited by David Johnson, Andrew J. Nathan and Evelyn S. Rawski, 292–324. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Woodside, Alexander 2002 “Classical Primordialism and the Historical Agendas of Vietnamese Confucianism.” In Rethinking Confucian-ism: Past and Present in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, edited by Benjamin A. Elman; John B. Duncan; and Herman Ooms, 116–43. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Asian Pacific Monograph Series.